Anne Morrow Lindbergh: Her Life (8 page)

Read Anne Morrow Lindbergh: Her Life Online

Authors: Susan Hertog

At precisely sixteen minutes before three, Lindbergh’s silver-winged plane dropped into view. It had taken him twenty-seven hours and fifteen minutes, only six hours under his meticulously planned flight to Paris. Still, it was nothing short of a miracle, compared with the Morrows’ torturous week-long journey in a railroad car.

Saluting the hundred and fifty thousand people who now waited in the hot sun, Lindbergh flew his plane until “it seemed to hang in

the air” and then descended in a long sweeping curve over the presidential box. Dwight Morrow, it was said, was the most pleased man in Mexico.

As if in gratitude, those on the field shouted bravos and hurled their broad-brimmed hats into the air. Unlike the Parisians, who had gouged his plane for souvenirs, these admirers took him up on their shoulders and carried him to the hangar. Instead of the ticker tape thrown by New Yorkers, the Mexicans deluged him with bouquets of flowers.

Morrow, driving with Captain Winslow, first secretary of the embassy, in his open car to greet Lindbergh, certainly did not expect an apology. As far as he and the thousands of impassioned spectators were concerned, the flight had been perfect. Lindbergh, however, was embarrassed at being two hours late. His railroad map had failed him, and his ignorance of Spanish kept him circling the towns, mistaking bathroom signs for station stops, challenging every ounce of his piloting sense, in spite of the clearing weather and the broad daylight. It had been, he felt, a poor showing for a friend.

The crowd, unconcerned with nuance, jumped the fences and swarmed the field, shouting “Viva Lindbergh,” and “Bravo, Lindy.” Lindbergh sat high on the rear fender of the car, just to make sure that everyone could see him. The throng on the field shouted with joy and stampeded toward the ambassador’s car, clinging to its doors and blocking its way back to the grandstand. Trapped by the crowds, Betty was terrified; people grabbed at her clothes, nearly tearing them off.

36

T

o Constance Morrow, the fourteen-year-old-daughter of Ambassador and Mrs. Morrow waiting at the stand, it seemed forever before the car returned. When it approached, she was nearly jammed through the railings by the photographers who rushed to see Lindbergh. While President Calles made a short speech and the mayor of Mexico City presented him with the keys, Constance kept her eyes glued on Lindbergh. Taken with the tall, sandy-haired flyer, she sent her impressions in a letter to Anne, still at Smith, preparing to leave for

Mexico.

37

To Anne’s amusement, Constance had enclosed a hand-drawn portrait.

Sitting in her room at school, Anne felt no excitement at the thought of meeting Lindbergh. Elisabeth, she was certain, would thoroughly captivate him, as she did all the other boys they knew, while Anne would sit awkwardly, feeling like a fool. As usual, she would find herself alone in her room, ashamed and inadequate, eloquently rehashing the conversation before the mirror. Men brought out the best in Elisabeth but made Anne feel stupid and worthless.

38

Her only consolation was the thought of seeing her mother and father. Returning to Smith without Elisabeth for her junior and senior years, and saying good-bye to her parents when they left for Mexico, had given Anne a taste of loneliness she had never known. And yet there was a feeling of separateness and strength she had never before permitted herself. No longer bound by her mother’s circle of vigilance, Anne relaxed and stretched beyond the edge.

She had always resented her mother’s double standard. Betty Morrow took the liberty of having her way. She went where and when she wanted, leaving the children at home with the nanny. Anne and Elisabeth, Dwight Jr., and Con spent many lonely nights in the nursery while their mother traveled through Europe, dining and entertaining, shopping for clothes, furniture, and art. It was for Morgan and Company, her mother would say, and later, during the war, for the Military Board. But her mother needn’t have gone with her father, and she needn’t have stayed so long. Betty Morrow was the perfect executive, Anne thought; she organized her children’s lives and left.

The truth was that Anne really didn’t know her father or her mother. They “never really talked to her,” she later said. They were constantly moving, never touching ground.

But Christmas at home had always been different. Time stopped, and the world was reordered. Life itself seemed reconfirmed. The whole family assembled under one roof, and nothing was more important than home and one another. In October, Anne had written to her mother that

Christmas away from the social mania of New York held the promise of a quiet family holiday.

39

But by December, she was beginning to wonder whether Mexico would be more of the same: dinners, parties, public events. More than ever, she would have to share her parents with others, to forgo the short moments of intimacy she treasured. Lindbergh’s arrival in Mexico the week before sounded more like the “French Revolution” than a diplomatic reception. She could not imagine her place in this brash timpani of personalities and diplomatic decorum.

A week on the sleeper train was enough to extinguish any glimmer of excitement. Never in her twenty-two years had she been more bored or more cold. It was a bit like “dying,” she wrote in her diary.

40

After boarding in New York, where she met Elisabeth and Dwight Jr., Anne had traveled to Chicago and then through St. Louis toward Laredo. The desolation and poverty of the small Texas towns seen through the window of her velvet-seated private car filled her with sadness. She was repelled by her parents’ affluence, by the “waste” and “artificialities” of their indulgent “walled garden” life, and yet she was comforted, even grateful for its insulation. How terrible to be left behind in this “savage” land of mud-built houses, she mused.

41

Elisabeth’s unaccustomed presence by her side rekindled her jealousy. Her sister’s delicately sculpted face, as smooth and translucent as fine alabaster, shone with new confidence. In the two years since graduating from Smith, Elisabeth had earned the respect of her parents. To their pleasure, she had become what they prized most: a teacher. The Morrows came from a long line of teachers, and nothing was more satisfying than passing on the tradition to their daughters. A teacher was a spiritual leader, her father had written, the finest goal of an educated woman.

42

Elisabeth pleased them so easily, just by being herself; Anne always seemed to fall short. The only thing she could do was write. But writing had always been for her more a necessity than a skill, a way of understanding people and sorting out her feelings and thoughts. She could say things on paper that she could never say to someone’s face. At

Smith she had learned to value her writing as a craft. She was praised for her insight and her scholarship and was encouraged by friends and teachers to publish. She thought about becoming a writer but feared that she lacked the tenacity to carry it through. She often wondered whether she really was talented. She had a boyfriend, known as P, a friend of the family, but he was painfully conventional and predictable. She was certain he saw her only in stereotype; he didn’t seem to know who she was at all. Perhaps, like her mother, she would give up a career for the “humdrum divinity” of married life. Marriage loomed like a grave inevitability—something large and yet too small to capture the “fire” she felt inside. She who “loved Scarlet” wore “a gown of black,” she wrote in a poem.

43

Suddenly the train arrived in Mexico City. They saw bright lights and small close streets as it slid into the railway station. Finding themselves on the back platform, they watched Con leap over the tracks from behind a car. Then they fell into one another’s arms.

44

There was so much to talk about that they could barely sort it out. Everyone talked so fast, asking questions and hardly waiting for answers. Were they all right? Were they safe and well? Where was the embassy? Could they meet Colonel Lindbergh?

If they hurried, their parents told them, they could meet him now. While their father jumped into another car, racing to see Lindbergh at the embassy, the children and their mother followed behind, hoping to catch Lindbergh before he left the reception.

Instinctively, Anne withdrew. Something had changed. This wasn’t like home at all. Things were different, faster, out of control. The way people looked at her, the way her mother spoke—the cars, the drivers, the clothes her mother wore. Lindbergh was breaking into their family party with all his “public hero stuff,” and she didn’t like it.

45

They sped, car behind car, through the brightly lit streets of the old city, and stopped before a huge eagle-crested iron gate. Once they honked loudly, the gate opened and they approached the embassy. Anne could see a massive door and, in the distance, a stone staircase. The steps were covered with red velvet, like a carpet laid out for a royal wedding.

Of course, Anne thought, Lindbergh would be “nice,” a “regular newspaper hero, the baseball-player type,” but he was certainly no one who would interest her—not of her world, not at all an intellectual.

46

Besides, she disliked good-looking men—“lady-killers,” self-absorbed and inaccessible.

47

Should she, she wondered, “worship Lindbergh like everyone else?”

48

They tumbled out of the car, dazed and shaken, as uniformed officers stood at attention on the steps. Climbing the plush stairway between the line of soldiers, Anne whispered to Elisabeth, “How ridiculous!”

49

Exhausted, at last they reached the top.

Then Anne saw a “tall slim boy in evening dress” standing against a “great stone pillar.” He was “so much slimmer, so much taller, so much more poised than I had expected. Not at all like the grinning ‘Lindy’ pictures.”

50

Betty hurried the introductions, breathlessly pushing Elisabeth forward. “Colonel Lindbergh, this is my oldest daughter, Elisabeth.”

From behind, Anne observed his fine-bone face and clear blue eyes. “And this is Anne,” her mother said.

Lindbergh didn’t smile. He took her hand and bowed.

Coming Home

T

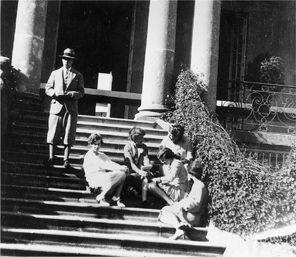

hree sisters, Anne Morrow, Elisabeth Morrow, and Constance Morrow, on the steps of the American Embassy in Mexico City, December 1927

.

(Lindbergh Picture Collection, Manuscripts and Archives, Yale University Library)

The attributes of True Womanhood, by which a woman judged herself and was judged by her husband, her neighbors, and society, could be divided into four cardinal virtues—piety, purity, submissiveness and domesticity. Put them all together and they spelled mother, daughter, sister, wife-woman. Without them no matter whether there was fame, achievement or wealth, all was ashes. With them she was promised happiness and power

.—BARBARA WELTER

,

The Cult of True Womanhood

HRISTMAS

1927, M

EXICO

C

ITY

A

nne scampered through the halls of the embassy buildings like a girl on a school holiday. She peeked in and out of the stone-walled rooms, draped with curtains and crimson tapestries. The smell of tuberoses wafted through the windows, and the cavernous fireplaces were laden with lilies. Growing tired of the darkened rooms lit only by the sun through slatted shades, Anne climbed to the roof of the embassy residence to peer over the garden wall. She felt the searing heat rise from the streets and heard the marketplace cries of the young native boys, herding their turkeys like flocks of sheep. She imagined herself a medieval princess in a royal tower, cloistered from the tumbledown squalor of the shanties below.

1