Antarctica (2 page)

Authors: Gabrielle Walker

This time it was a Norwegian team. Four of them had been riding skidoos to the South Pole, hoping to retrieve a tent left there back in 1911 by the great Norwegian hero Roald Amundsen. Amundsen was one of the most famous people ever to set foot on Antarctica, the conqueror of the Pole, the winner of the race to the bottom of the world. This was now 1993 and the tent had been buried by decades of snow, as well as shifted by the moving ice. But the men were confident they could find it, dig it up and take it home in triumph to be displayed next year at the Lillehammer Winter Olympics.

Now, however, they had run into difficulties. A thousand kilometres from their goal, someone had fallen into a crevasse. They had set off a distress beacon, which had rung bells with the Norwegian government, who had called the American government, who had called the US National Science Foundation, who had called the base commander at McMurdo, who had called Steve.

For a nearby emergency, the SAR team could be on the road in about twenty minutes, but the region where the Norwegians were now trapped was about as remote as it was possible to be. While Steve organised a team of seven people and packed up 1,000 lb of gear, the aeroplane coordinators diverted a ski-equipped Hercules from its mission to service a remote science station.

Hercs are heavy planes, far too heavy to take out to a crevassed accident site. This one took the team on the three-and-a-half-hour flight to the Pole, where Steve chose three trusted membersâa Navy medic, an American mountaineer and another mountaineer from the New Zealand base near McMurdoâto join him on a smaller Twin Otter plane. They would take some gear, scout out the situation and call in reinforcements as necessary.

By the time they reached the site of the accident, in the Shackleton Mountains, more than a day had passed since the beacon had flared. The pilot spotted a tent and buzzed down low, a hundred feet above the surface, but nobody emerged from the tent. That was a bad sign. There had been radio contact with the Norwegians from the Pole but that had stopped a few hours ago. Through the Twin Otter's window Steve could see countless holes where their skidoos had broken through snow bridges; he could see the tracks where they had hit dunes in the snow and then flown through the air. They must have been going at top speed, vaulting over crevasses, surrounded by danger, holes opening up all around them, scared to death. There were three skidoos parked next to the tent. And about two hundred feet away, one hole had ropes dangling forlornly down into it.

The closest landing site they could find was nearly three miles from the tent. As the Otter taxied after landing, a snow bridge opened up on the left-hand side, leaving a hole that the plane's ski could easily have tumbled into. There were crevasses

everywhere

. Any hopes of bringing in reinforcements now vanished. This was going to be a one-stop mission, to find the casualty, bring him back to the plane and get back out of there.

The team was roped up and ready before they even climbed down on to the ice. Steve took the lead, probing every step with a thin pole almost as tall as he was. His arm quickly grew tired from the repeated lifting and thrusting. The snow was like sugar, so full of air that he could hardly tell where snow finished and hazardous crevasse began. In spite of their care the four of them plunged repeatedly through the snow, their ropes holding firm, their legs dangling over invisible chasms.

And the crevasses were unbelievably chaotic. Instead of the usual parallel lines like stretch marks in the snow, these were a crazy paving of zigzags running every which way. That's really dangerous. Normally you can approach crevasses from the side and then step over them, knowing for certain that even if you fall in, the person behind you won't. But if you can't predict their directions, all four of you could be on the same snow bridge over the same crevasse at the same time. And if you all break through into the same crevasse at once, everybody falls. Steve's sense of responsibility grew heavier with every dogged step. At what point did his obligation to protect the people behind him on the rope begin to override his obligation to help the people he'd come to save?

He kept going; they all did. Four hours of slog just to travel three miles. When they were just a few yards away from the tent, two of the Norwegians finally climbed out to greet them. Steve could tell straight away that they were shot to pieces emotionally. Inside the tent, one of their companions had cracked ribs and concussion. He'd been the first to fall. His skidoo had broken a hole big enough to plunge into and he had gone with it. Luckily for him he had smashed into a ledge in the crevasse and stuck there, unconscious, while his skidoo crashed on down into the abyss. When he came to, he had managed to climb out using a chest harness and ropes that his companions had thrown to him. A chest harness with broken ribs? That must have been agony.

It was after this that the others had set up the tent. But then the real disaster hit. The team's second in command, an army officer named Jostein Helgestad, had decided to try to find a safe passage through the crevasses on foot. His companions had seen him disappear into the ice just a stone's throw from the tent. And they had heard nothing from him since.

Somebody had to look, so Steve secured a rope to one of the skidoos and went in. Sixty feet down, the crevasse was so narrow that he couldn't turn his head for fear of knocking off his headlamp; the danger was now not falling so much as getting wedged in. His legs were splayed, his crampons snagging on the ice walls. He couldn't control his own rope any more; his companions up on the surface were going to have to start lowering him. He yelled up instructions then pivoted vertically so that he was descending head first into the darkness. His headlamp picked out a sleeping bag that had been thrown down by the Norwegian team and had evidently been left untouched. Then he saw his man.

The crack was now barely a foot wide. Jostein was wedged in sideways where he had fallen and where his body heat must have melted him further into the ice. Steve strained to touch him but couldn't quite reach. Instead he probed down with his ice axe, snagged Jostein's arm and gingerly raised it. The arm was frozen solid.

No hope, then, of even retrieving the body, but there were still three people to save. Back on the surface, Steve gave more instructions. The Twin Otter was neither big enough nor fuelled enough to take a heavy load. The only way they could all get out was to abandon everything. They left tent, skidoos, clothes, harnesses, ropes, everything except the gear they needed to get to the plane. Steve found himself explaining the principles of roped glacier travel to a man who was still seeing double from concussion and two others who were dazed at the disaster that had befallen them.

And then there was the long perilous slog back, a careful check for crevasses along an improvised runway, more gear ditched, more load lightening, and a take-off for which everybody held their collective breath before the plane finally rose into the air over Antarctica's bright white hinterland.

Nearly twenty years later, Jostein Helgestad is still there, his frozen body held fast by a continent that punished his boldness without hesitation or particular interest. The truth is that Antarctica has little time for humans. We have managed to colonise most of our planet, to get by in apparently hostile deserts, forests and mountains. Even at the North Polar ice cap, which is a frozen ocean surrounded by continents, the sea ice is just a thin skin and the animals that swim beneath have provided humans with food and fuel and clothing for thousands of years. But Antarctica is different. It is a vast, isolated stretch of rock, almost completely buried under thousands of feet of ice. This is the only continent on Earth where people have never lived. And until very recently in human history it was as mysterious to us as the Moon.

Even today, the temporary bases that dot the continent are miniature life-support systems, human toeholds on the edge of a vast, alien landscape, for which everything you need to survive has to be brought in from the outside. Yet people still go there in their thousands every year, as scientists, explorers, adventurers and the incurably curious.

But curiosity can also be perilous. And if you do find yourself in trouble, the phone will again be ringing at McMurdo Station, the biggest of all the bases, logistics hub, unofficial capital of Antarctica and gateway to the ice.

Â

Â

Â

Â

PART 1:

Alien World

1

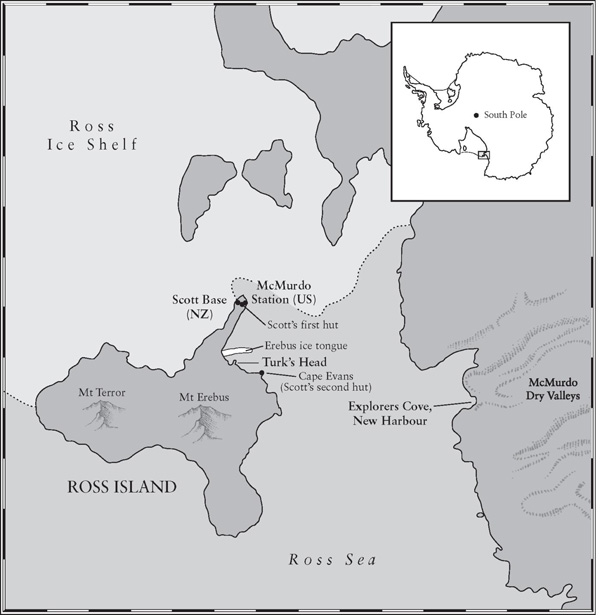

McMurdo Station lies on a volcanic island, as far south as you can sail from New Zealand before bumping up against Antarcticaâwhich is how the earliest explorers discovered it. These days, however, most people fly there, in big, noisy, military troop transporters, strapped into webbing seats and packed around with cargo.

If you're lucky, you'll get through first time. If you're unlucky, the weather will turn bad just before the plane reaches the âPoint of Safe Return' at which there is still enough fuel to make it home, and you will boomerang back to New Zealand, for another long, uncomfortable try tomorrow. (The far end of the boomerang used to be known as the âPoint of No Return', but was changed for purposes of reassurance.)

Known to its inhabitants as Mactown (or just âtown'), McMurdo is the operational headquarters of an American research programme that reaches out from here to the entire continent. But if this is your first sight of Antarctica, and you're expecting great sweeping vistas of snow and ice, you're likely to be surprised.

Coming in from the sea ice runway, on a massive bus whose wheels are taller than your head,

1

you bump endlessly over invisible obstacles, craning your neck to try to peer through the windows. But they are hopelessly steamed up by the crowds of people around you, who are all quietly overheating in the many regulation layers of clothes they have been obliged to wear in case of breakdown.

And then at last you arrive, and tumble down the steep steps of the bus to see . . . a grubby, ugly mess. McMurdo itself has no ice and little romance. It is more like a mining town, planted squarely on dirt. The buildings are squat and mismatched, with tracked vehicles and heavy plant lumbering along the roads in between, churning up the black volcanic soil and spreading dust and grime. There is nothing to soften that hard industrial edge. You will find no trees or other vegetation here, and nor are there children or non-native animals. All foreign species other than adult humans are banned.

I remember my first few hours at Mactown, but they were also strangely blurred. There was a constant buzz of helicopters overhead; trucks were shifting materials from one building to the next. People were running past, dragging the big orange bags that were issued to everyone back in Christchurch, to carry the regulation red parka and wind pants, and thermals, and water bottle, and a bewildering array of gloves and mitts and scarves for every occasion. Others were heading down to the sea ice on skidoos that roared like motorbikes. And we newbies were trying to fill in the many, many forms, and take in the dizzyingly detailed instructions about where we needed to be, when, and why, and with what.

At one o'clock in the morning when everyone else had finally got off to their allocated dorm rooms to sleep, I stole away in the bright midnight sunshine to the edge of town and climbed up Observation Hill, a local cinder cone shaped like a child's drawing of a volcano.

The path was rocky but clear and after about an hour I reached the summit, marked by a tall wooden cross. This was erected back in 1912 by the colleagues of the doomed Captain Scott, after he lost his life on the way back from the South Pole. It was inscribed with the names of the five men who perished, along with a line from âUlysses' by Alfred, Lord Tennyson: âTo search, to seek, to strive and not to yield'.

Scott based his two Antarctic expeditions on Ross Island. The second expedition, the more famous of the two, started from Cape Evans, around the coast from here. But the first was built at âHut Point' at the end of the peninsula in front of McMurdo. I could see it now over in the distance, near where the icebreaker ship docks on its annual resupply. With its clean wooden walls and tidy low roof, the hut looked as if it were built yesterdayâa reminder both that ice is a great preserver, and that the heroic age of Antarctica wasn't so very long ago.

I sat with my back to the cross and thought about the many dramas that had taken place around that small hut. The messages fixed to the door for returning field parties, which had spoken of disaster at least as often as triumph. The people who had trudged and strained their way over the ice, hoping for bright lights and a warm welcome, and found only darkness.

To the left I could see the white expanse of the great Barrier, a floating glacier the size of France that we now call the Ross Ice Shelf. Its edges form giant cliffs of ice above the ocean (and even bigger stretches of ice below), which prevented the early explorers from sailing farther south than here. Instead, any attempt to reach the South Pole meant slogging for hundreds of miles over its surface, a place that one of Scott's men described as âa breeding place of wind and drift and darkness'. It was on the Ross Ice Shelf, some ninety miles from here, that Scott and his men finally succumbed to cold and hunger.