Antarctica (6 page)

Authors: Gabrielle Walker

But, then, I shouldn't be so quick to interpret the sounds Weddells make. They have twenty different vocalisationsâeverything from a chugging truck noise to high-pitched chittering. I have heard recordings of whistles, booms, gulps and chirrups. They emit alien whooshing electronica, sounds that shouldn't rightly come from any animal, let alone a furry one.

9

Bob told me that you could hear these sounds in the camp outhouse, resonating eerily up through the hole in the ice.

As he spoke, I was trying to take notes but my pen was giving me trouble. I scribbled irritatedly, wondering why it had so abruptly run out of ink. Mark glanced over. âYou're not using a pen are you?' he said incredulously. âYou can't do that out hereâthe ink freezes! Here.' He rummaged in his pocket and handed me a pencil. I noticed belatedly that the people noting down seal weights and dimensions were all using pencils. My issue gear was so warm, I'd forgotten that it was still sub-zero here.

Chastened, I left the team to their weighing and wandered off among the sparsely scattered colony. Near me, a seal abruptly poked her head through one of the two breathing holes, surrounded by slushy ice crystals. She blinked. Her eyes had a purplish bloom; they seemed to be all pupil, perhaps to help her hunt in the dark. Droplets of water dangled like beads on the ends of her whiskers. For a while she just hung there, inhaling deeply through her nostrils, holding her breath as if savouring the sensation, then releasing it with a snort. Each time she held her breath, I found myself holding mine, and then gasping on her behalf.

Suddenly she opened her mouth wide, called loudly, with a deep-throated âcoo-ee', disappeared from view, and then hauled out in a dramatic whoosh of water and slush. Even though she came out on the opposite side of the hole from me I leapt back in alarm and Bob looked over and laughed. âWahay! That was a thousand-pound rocket!' The call was to her pup, who responded by hurrying over and clamping to her invisible nipple like a limpet.

Bob told me that this urgent feeding process was the most important adaptation the Weddells had made to living down here, on the edge of survival. First the mothers store vast amounts of energy in their blubberâwhich is why they look so pumped up, as if their skin was ready to burst. Then they quickly dump an astonishing quantity of this into their pups. When they are nursing, even their blood is so full of fat it looks thick and creamy like a milk shake, and their milk itself is like warm wax. From just before birth to weaning, the mothers will lose nearly half their body weight in less than forty days. Bob pointed to a pregnant seal. âRight now she looks like a fuel bladder. After she's pupped and weaned she'll look like a long thin cigar.' And the pups go the other way. They start at about seventy pounds, and within a month they will weigh five times as much.

The effectiveness of this process is crucial for survival. Pups are more likely to live through to weaning if they are born to a larger mother.

10

And the heavier the pup when it is weaned, the more likely it is to survive to adulthood.

11

I like this. Survival not of the fittest, so much as the fattest.

I also like the team's other key finding. For clearing those two hurdles of first survival through to weaning, and then to maturity, it helps immensely to be born to an older mother. The svelte young things of maybe six, which have only just started to breed, turn out to be less effective at raising pups than the ones that have been around the block a fair few times. The researchers think this is because the older the mother is, the fatter she is likely to be and the more energy she can pump into her offspring. (The benefit disappears when the mothers get really old. In a reversal of middle-age spread, a twenty-two-year-old Weddell has such worn-down teeth from gnawing on years of sea ice that she is a less effective hunter, and hence tends to be less substantial than, say a fourteen-year-old.)

12

The rest of the team was now struggling with a mother-pup pairing that didn't want to play. They had managed to drag the pup over to the weighing sled as bait, but it was thrashing and wailing. The mother had humped her way over to the sled but refused to get on. She rolled over, buried her nose in the snow, arched her back and then tried to get out of the way of the student blocking her path. Everyone was still and silent. Would she settle? No, she rolled away again. âShe's not going to do it. We'll leave them be.'

They released the pup to rejoin its mother and, once again, they were now both as docile as ever, the drama apparently forgotten. Still it seemed like hard labour, and I could see that every data point was dearly won. I asked Bob why he was prepared to put in so much effort.

âThe best ecological insights come from living in the field and grunting around from day to day,' he said. âYou can use satellite images all you like but you don't really learn things until you are watching them every day saying “why are they doing that?”

âMost of the time on the ice they are just sleeping and nursing. But if you look at the same animals again and again you start to realiseâthat's a good mom, that's a bad one, that's one's mellow, that one's psycho.

âSometimes if you look down a hole with a parka over your head to block the light you can see them below the ice, perfectly at home in water that's at 28°F. I'm constantly amazed at how they survive in such a crazy environment that shouldn't support life. And you know what? They don't just survive there. They flourish.'

On the way back to town, I thought about those mothers urgently fattening up their pups against the coming winter, and how in spite of this four out of five of the pups would die. That McMurdo mantra may be said ironically but it was also true: this

is

a harsh continent. And I was beginning to feel that we humans, the newcomers, could learn a lot from the creatures that had spent thousands or even millions of years figuring out what adaptations it takes to flourish here.

2

David Ainley looked like an ageing surfer dude, or a mountaineer who had spent a little too much time squinting into the sun and wind. He was in his early sixties and had been coming to Antarctica for ever. He had an untamed shock of white hair, a heavily tanned face, a moustache that he keeps when he's off the ice, and a beard that was here just for the season. I had been warned that he wasn't so good with people. âTaciturn' was how some had described him to me, and âa bit wild'. He spends as much time as possible out here in his field camp, among his penguins, and as little as he can back in Mactown.

1

David was Californian, a biologist from an ecological consultancy in San Jose. He spoke slowly and hesitantly, as if he couldn't quite remember how you're supposed to talk to other humans. Sometimes he put invisible inverted commas around his words and pronounced long ones in an exaggerated way as if he were making some kind of joke. He often was making some kind of joke. I liked him immediately.

He pulled on his coat as I entered the main research tent.

âCome on then,' he said. âLet's see how many smiling faces greet us.'

âHuh?'

âPenguins are always smiling. They have no self-doubt.'

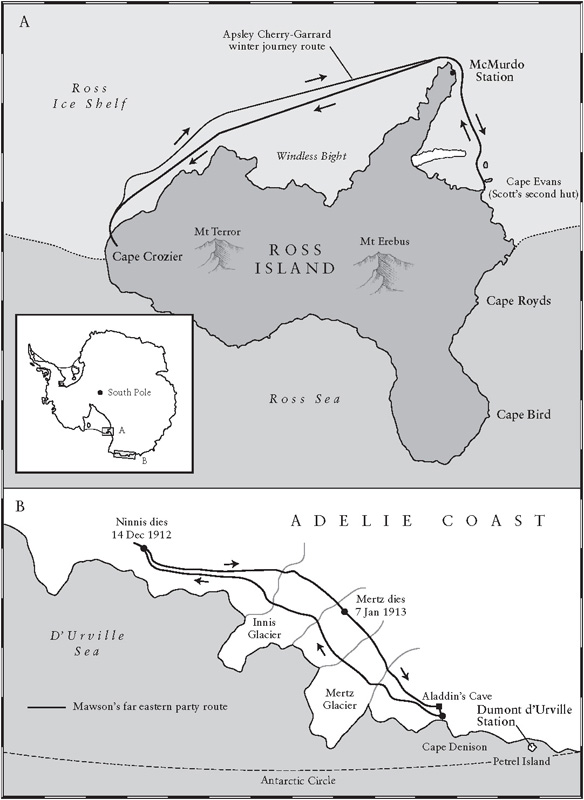

We stomped out of the tent in our bunny boots and headed down towards the sea. David's camp at Cape Royds was a short helicopter ride from McMurdo, on the westernmost tip of Ross Island, and was home to a colony of Adélie penguins. They are classic cartoon creatures, knee-high, with black heads, flippers and backs, white throats and chests, and a bright white ring around their eyes. They are pathologically busy, packing their entire breeding cycle into the brief Antarctic summer. Adélies are also cute and comical. And everybody, but everybody, loves them.

I, however, did not. Even before I met them I was already tired of penguins. From the moment I started to talk about Antarctica to my friends and family I began to receive a mountain of penguin paraphernalia. There were penguin T-shirts, penguin cards, penguin jigsaw puzzles, cups, mugs, glasses, playing cards, a penguin apron, penguin pyjamas. For birthdays, Christmases, or for no particular reason I received penguin backpacks, pencils, rulers, scarves, gloves, big furry penguins, small furry penguins, penguin place mats and cutlery. When I outlawed penguin presents they still came in. âIt's just a small one. I couldn't resist.'

Well, I could, quite happily, and I was determined to resist the charms of the real Antarctic thing. Penguins are the clichés of Antarctica, annoyingly cute icons of a continent that is otherwise wild and vast and mysterious. I saw them as our way of diminishing the ice; we anthropomorphise them, personify them, imagine them to be amusing little people, and in the process we bring the continent down to a manageable human scale. I hated that idea. So although I love animals in general, I had told my friends and I had told myself that I would not, repeat not, fall in love with these creatures. I would write about penguins because there was interesting science to tell. That was all.

It was a gorgeous day, barely below freezing, with a bright sun reflecting off the sea ice that was crammed up against the shore. Most of the ground was bare volcanic rock, and Mount Erebus's bulk dominated the scene, topped with its customary cloud.

David told me that Adélies choose to settle their colonies in rocky placesâto keep their eggs safe from iceâand those that are also close enough to the sea to enable them to fish for food. But although we were looking down on to McMurdo Sound, there was no open water between here and the horizon, just endless sea ice that had been squeezed into ridges and scattered chunks as if a giant child had thrown toy blocks out of its pram. A fat Weddell seal had hauled itself out of a crack in the distance. Seven Adélies were making their arduous way back, stumbling and falling flat in the gaps between ice chunks, scrabbling with their flippers to pull them through. It looked hard. There was still a fair way to go before they reached the rocks, and then another stiff climb uphill to the colony proper.

We passed a small pond half clear of ice with a running stream spilling out over the rocks, the edges scattered with white eggshells. And then we reached the colony, and the noise raised itself from a rumour to a roar; it sounded unhinged, like a cackling orchestra of kazoos. The fishy guano smell was noticeable, but not nearly as strong as I had been expecting. Although the nests were densely packed on the ground, I supposed in this big open spot there was enough wind to whisk the ranker smells away.

By contrast with the bustling birds heading to and from the sea ice, the ones on the nests were placid, and even listless. Every so often one stood up, stretched and flapped its wings, revealing the bare pink patch on its belly that fitted neatly over the eggs, skin to shell, to ensure that maximum warmth reached the chicks inside. David told me that they would usually lay two eggs apiece but this year there had been quite a few single clutches.

A skua landed and started prowling. It looked like a seagull but larger and brown with a wickedly curving beak like a hawk. I'd seen skuas at McMurdo, and been warned that they would snatch a sandwich from your hand if you let them. They are scavengers, always out for an opportunity to harass, bully or steal. This one was clearly eyeing up the eggs. The nearest penguins stretched their necks menacingly like guard geese ready to hiss. They shuffled round, keeping their eggs out of sight beneath them, maintaining eye contact with the enemy.

âWhy doesn't the skua just attack?' I asked.

âIt's afraid of the penguins, with good cause,' said David. âSkuas may stand as tall as penguins but they are all air and feathers. They only weigh maybe nine hundred or a thousand grams. The penguins are much denserâthey can weigh seven or eight kilograms. And those flippers are very hard. A whack from one of those and a skua definitely remembers it.'

That doesn't stop them from looking for a quick thieving chance. While our skua was getting nowhere, a burst of indignant squawking erupted to our right and another bird flew overhead, barely able to hold the outsized egg in its beak. The penguins settled back down on their nests. There was no sign of where the egg had been taken from. Everyone seemed resigned.

Now in mid-December, the Adélies were almost halfway through their race against time. Each year they must pack every relationship stage of meeting, wooing, mating, hatching, rearing and weaning their young into the few short months of the summer season.

They come here in early November at the start of the southern summer and hastily reconvene with last year's partners. There is little time wasted on courting niceties or on excessive fidelity. If you're a day or two late, your former mate will already be on to someone else. The first eggs come about a week later, and by two weeks most of them are laid.

The penguins are fat when they first arrive, having stocked up on fish for the season. As soon as she has laid her eggs the female heads back to open water to replenish, and the male incubates the eggs and keeps the skuas at bay. If he's lucky, she'll be back within two weeks to relieve him.