Antarctica (29 page)

Authors: Gabrielle Walker

Â

I had been at the Pole for barely four weeks, in the bright white summer with a station continually crowded with new arrivals; and yet when I heard the moaning sound that meant the plane was coming to take me home, I felt a sadness that lingered for most of the journey back. There were only two of us on the flight to Mactown, so I wheedled my way on to the flight deck and spent the ride staring out of the window at the great white plateau and daydreaming about the final days of Scott and his men.

After they left the Pole, they followed their own tracks home, sometimes gaining enough wind to sail on their sledges, but mostly doing the Antarctic man-hauling trudge. At first all seemed well; they were reaching each of their caches of food and fuel just before their supplies ran out. But the temperature began to plummet and their skis stuck fast on the frozen snow, as if they were pulling on sand. As the way grew harder so the men grew weaker.

We were flying down the Beardmore Glacier now, where Edgar Evans succumbed to a hand injury that refused to heal, and then head injuries from a series of falls, then the depredations of frostbite. He died somewhere near the bottom of the giant ice staircase. Now we were above the floating Ross Ice Shelf, the great Barrier, where the ailing Captain Oatesâwho knew he was holding the rest of his companions backâstepped out into a snowstorm. Scott, his loyal lieutenant Wilson and the indefatigable Birdie Bowers continued onwards, but it must have been somewhere around here where the three men made their final camp.

They were less than a day's march from a depot of fuel and food, but a blizzard kept them trapped in their tent until they were too weak to move. On 29 March 1912, Scott wrote in his diary: âIt seems a pity but I do not think I can write any more.' And then later, in one famous anguished scrawl: âFor God's sake, look after our people!'

Poor Apsley Cherry-Garrard had been sent out with the dogs from Cape Evans, to reprovision the depot. He did so merrily, unaware that his companions were close to death just eleven miles away. He didn't look for them. He had been told not to. At that stage nobody imagined the polar party might be in danger and he had been warned not to put the dogs at risk. Still he was haunted all his life by the thought of what might have been.

The next spring, when the men from Cape Evans found the bodies, they turned the tent into a tomb. Long buried by successive snowfalls, it has travelled along with the ice, heading inexorably towards the coast. Nobody knows exactly where the corpses are now. But one day they will reach the edge of the great Barrier. When the ice around them calves off into an iceberg, they will go, too, and they will finally find rest, and decay, when the berg melts and they drift gently to the bottom of the sea.

Amundsen, of course, returned home to Norway, and glory. But though he was feted the world over, he was never really content with his triumph. He made voyage after voyage to his first love, the far north, almost daring the elements to take him. Eventually he disappeared in 1928 while flying on a rescue mission over the North Pole, as if that was the only fitting end for a true polar hero.

When an expedition goes fatally wrong, it is easy enough to find fault with the explorers' decisions or with their methods. Do so if you dare. But, first, remember the words of Charles Dickens, chiding those of us who would criticise too readily: âHeaven forbid that we, sheltered and fed, and considering this question at our own warm hearth, should audaciously set limits to any extremity of desperate distress! It is in reverence for the brave and enterprising, in admiration for the great spirits who can endure even unto the end, in love for their names, and in tenderness for their memory, that we think of the specks, once ardent men, “scattered about in different directions” on the waste of ice and snow.'

26

Scott may have made mistakes, but his luck was also against him. One atmospheric scientist, exasperated by all the carping she heard about Scott, decided to calculate some of the odds around the two approaches.

27

Interestingly, although Scott's two huts still stand, there is no trace of Amundsen's camp. The place he chose to spend the winter has since broken off into a giant iceberg and floated out to sea. There was a one in twenty chance this would happen while Amundsen was there. He took the risk, played the odds and won. There was also, as it happens, only a one in twenty chance that the weather would be cold enough during Scott's return from the Pole to slow him and his colleagues down until they ran out of food and fuel. Scott was also playing the odds, but he turned out to be the unlucky one.

28

And yet, these dramatic tales and the language that goes with them do help to burnish the image of the ice as hostile and alien, inimical to those warm-blooded creatures foolish enough to try to penetrate it. The changes at Amundsen-Scott South Pole Station seem similarly designed to perpetuate the myth. The Dome is now gone and the new space-age station finished, cladded with its iron-grey coat. Today the thirty-foot South Pole Telescope has begun probing deeper into the afterglow of the Big Bang. The last string has been frozen in for Ice Cube and the South Pole's neutrino eyes have opened.

These changes lend further weight to the notion of the South Pole as distant and alien. But there is another scientific side to the Pole, one that's looking inwards rather than out. Think of ARO, testing our own world's air, and SPRESSO's seismic ear, pressed close to the ground to hear the slightest ringing of the quiet Earth.

Larry Rickard's last words to me, when he came to see me off at the plane, echoed this from the personal side. âI've listened to people talking about what's the meaning and the feel and the heart and the soul of this place,' he said. âBut you can't. It's like trying to find the meaning of life. To me, this place, it just is. But I'll tell you one thing. When you come here you're not finding something in a desert, you're seeing a mirror. Antarctica tends to knock you down to what you really are.'

Jake Speed clearly understood this. He lay on the snow in the dark, cold winter, watching sastrugi grow grain by grain: but he also said that it is all about the people. And I remember now how Jake described this place that he knew better than anyone else alive. He didn't use words like âhostile' or âunforgiving' or even âindifferent'.

He called it âpatient'.

5

Â

It is 800,000 years before the first humans set foot on Antarctica, and snow is falling. Not the exquisitely intricate flakes that you find near the coast; the snowflakes here in the interior are more like tiny misshapen lumps. Most of their delicate fingers have been sucked away by the dry air, and the rest break off as the crystals tumble and roll on the surface, harried this way and that by the wind, until they finally settle into a hollow and are buried by more flakes from above.

Dim light filters through as snow piles upon snow. Someone walking on the surface now might hear a muffled popping sound, like bubble wrap bursting, as pressure from their footsteps causes the snow crystals to join together and break apart. But there is nobody to do the walking.

Homo sapiens sapiens,

the human race itself, has not yet evolved.

Still, the snow changes subtly where it lies. The warmth of the summer sun is just enough to meld its crystals into a distinctive crusted layer, which will mark out this year's snowfall from the one below, like the growth ring on a tree. And then winter comes and then summer, and another year's snow has fallen, and another. The layer gets buried, and the weight of snow overhead presses it into a new form called âfirn'. It becomes rigid, with the texture of polystyrene, threaded with crannies and tunnels through which the air passes freely from above.

Years pass. Now there is no more daylight. The burden overhead grows heavier, until finally it squeezes so hard that the crannies and tunnels collapse, slamming shut the exits, and trapping tiny bubbles of ancient atmosphere. The firn layer has now officially become ice and its cargo will turn out to be a precious one.

In far-off Africa, the ancestors of modern humans are making their way out into the world, outcompeting the Neanderthals for the world's resources. They are surviving ice ages, making tools and fire, growing crops, building cities and burning them down. And all the while our layer descends in the silent darkness towards the bedrock as a mountain of ice builds from above.

And now the humans are building roads and cars and factories. They are learning to burn fossil fuelsâcoal and oil and natural gas. And they are belatedly learning that their activities are changing the atmosphere, and perhaps also the climate that they depend on for their life.

The only way to find out for sure is to measure what came before. But it's too late for that. The air around them is already pumped full of pollutants, and the information these humans need to understand their world is now long gone. Except, that is, in those deep dark pockets of ice, where ancient air still lingers. Perhaps scientists can find these places, beneath the continent's great domes where the ice is thickest and oldest. Perhaps they can drill down into this ice, capture its unpolluted air and read the many layers of its long, cold climate history.

Â

Dome C is one of a handful of points on the East Antarctic Ice Sheet even higher and drier than the South Pole. The summit stands more than 10,000 feet above sea level; the ice sheet is almost as thick as it gets, and the layers of ice at its base are among the oldest on Earth.

From the air I was half expecting it to look obviously pointed, like an ice mountain. But in fact its summit was so broad and its slopes so distant and gentle that it seemed just as flat and white as every other part of the vast Antarctic interior.

And when we landed, the sunlight on snow was just as blinding as at the Pole, the shock of taking my first breath in a temperature of -40°F was the sameâas the air flash-froze the mucus in my nose and scoured the back of my throat. But there were some differences. At the Pole, it was always windy but here I could feel no wind at all. That was a benefit of being in a place where the great Antarctic winds were born. The air from these domes might spill down to the coast with great ferocity, but here it was surprisingly still.

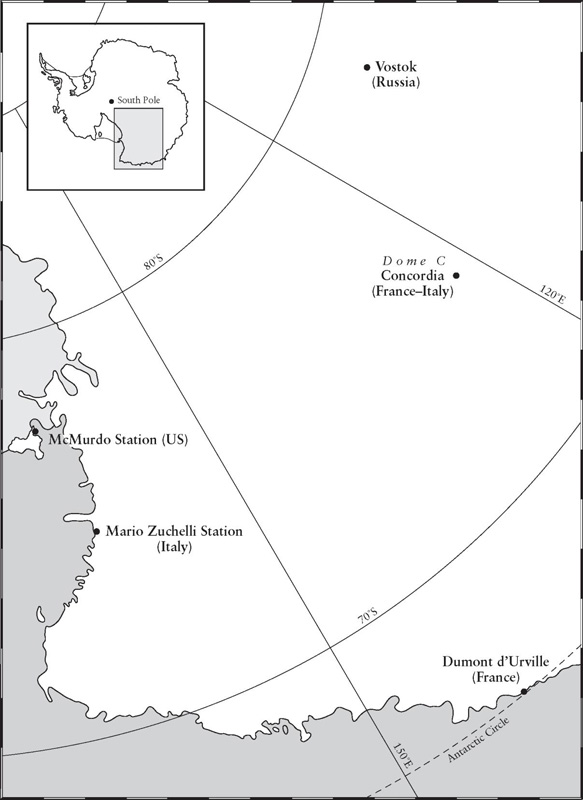

Dome C lies about 600 miles south of the French coastal base of Dumont d'Urville, about the same distance from the Italian coastal base of Mario Zuchelli Station at Terra Nova Bay, and nearly 1,300 miles from the South Pole. Its name came originally from an unimaginative application of letters of the alphabet to the various high points that geographers discovered, and it has been variously dubbed Dome Charlie and Dome Circe. But these days the C is more likely to be associated with âConcordia', because that is the name of the new station being built here, jointly, by France and Italy. The previous base had temporary buildings that could be occupied only in the summer. This one would now be available in the winter, too.

I was intrigued to see the only station on the ice that was run by two completely different countries. True, the French and Italians share a certain romance in their language and culture, and a similar obsession with food, but a co-owned base seemed odd even for Antarcticaâthe most collaborative of continents.

Their influence was immediately obvious. I remembered arriving at the South Pole and receiving stern injunctions from the Americans on preventing altitude sickness. Drink plenty of water, they had said. Avoid caffeine. Avoid alcohol. Here, our Twin Otter was greeted by a Frenchman bearing a tray of glasses filled with champagne; and at the first building we reached an Italian offered us dense, rich espressos.

The clichés extended to my hosts' clothing. As usual on the ice, the nations were neatly colour-coded, with the French wearing blue cold-weather gear and the Italians red. But although my American gear was also red, my parka felt suddenly ungainly The Italian parkas were svelte and sleek. Some people were wearing one-piece suits, nipped in at the waist, with darts and tucks and strategically placed black patches. They looked like Formula One racing drivers. The Americans may have the only ATM on the continent, the French may pay most attention to food, but it was immediately evident that the Italians wore the most stylish clothes.

The base was much smaller than the Pole, more like Dumont d'Urville in scale, with about fifty people here in the summertime. From the outside the buildings looked like shipping containers welded together. The first room, the one with the espressos, was lined with wood, like a chalet. As I lingered there, Rita Bartolomei, the station secretary, came to show me where to go. She was Italian, open, cheerful and very beautiful, with an air of utter dependability. As we walked down the dormitory corridor to a small room with two bunks, and a square window through which the sunlight was pouring, she told me I was lucky. Most of the workers here slept outside in long cylindrical tents heated with stoves. If you left your clothes on the floor at night there, in the morning they would be frozen. In fact, most of the other buildings here were tents, and the locals referred to this as a âsummer camp' rather than a station.