Antifragile: Things That Gain from Disorder (16 page)

Read Antifragile: Things That Gain from Disorder Online

Authors: Nassim Nicholas Taleb

Let us consider bones again. I have a thing for bones, and the idea I will discuss next made me focus on lifting heavy objects rather than using gym machines. This obsession with the skeleton got started when I found a paper published in the journal

Nature

in 2003 by Gerard Karsenty and colleagues. The tradition has been to think that aging

causes

bone weakness (bones lose density, become more brittle), as if there was a one-way relationship possibly brought about by hormones (females start experiencing osteoporosis after menopause). It turns out, as shown by Karsenty and others who have since embarked on the line of research, that the reverse is also largely true: loss of bone density and degradation of the health of the bones also

causes

aging, diabetes, and, for males, loss of fertility and sexual function. We just cannot isolate any causal relationship in a complex system. Further, the story of the bones and the associated misunderstanding of interconnectedness illustrates how lack of stress (here, bones under a weight-bearing load) can cause aging, and how depriving stress-hungry antifragile systems of stressors brings a great deal of fragility which we will transport to political systems in

Book II

. Lenny’s exercise method, the one I watched and tried to imitate in the last chapter, seemed to be as much about stressing and strengthening the bones as it was about strengthening the muscles—he didn’t know much about the mechanism but had discovered, heuristically, that weight bearing did something to his system. The lady in

Figure 2

, thanks to a lifetime of head-loading water jugs, has outstanding health and excellent posture.

Our antifragilities have conditions. The frequency of stressors matters a bit. Humans tend to do better with acute than with chronic stressors, particularly when the former are followed by ample time for recovery, which allows the stressors to do their jobs as messengers. For instance, having an intense emotional shock from seeing a snake coming out of my keyboard or a vampire entering my room, followed by a period of soothing safety (with chamomile tea and baroque music) long enough for me to regain control of my emotions, would be beneficial for my health, provided of course that I manage to overcome the snake or vampire after an arduous, hopefully heroic fight and have a picture taken next to the dead predator. Such a stressor would be certainly better than the mild but continuous stress of a boss, mortgage, tax problems, guilt over procrastinating with one’s tax return, exam pressures, chores, emails to answer, forms to complete, daily commutes—things that make you feel trapped in life. In other words, the pressures brought

about by civilization. In fact, neurobiologists show that the former type of stressor is necessary, the second harmful, for one’s health. For an idea of how harmful a low-level stressor without recovery can be, consider the so-called Chinese water torture: a drop continuously hitting the same spot on your head, never letting you recover.

Indeed, the way Heracles managed to control Hydra was by cauterizing the wounds on the stumps of the heads that he had just severed. He thus prevented the regrowth of the heads and the exercise of antifragility. In other words, he disrupted the recovery.

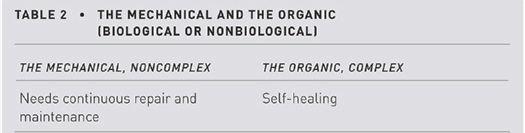

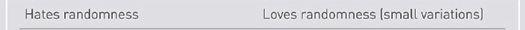

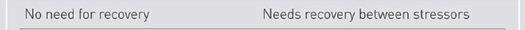

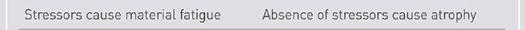

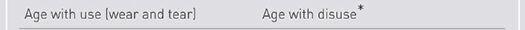

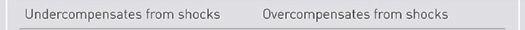

Table 2

shows the difference between the two types. Note that there may be intermediate steps between engineered and organic, though things tend to cluster in one bucket or the other.

The reader can get a hint of the central problem we face with top-down tampering with political systems (or similar complex systems), the subject of

Book II

. The fragilista mistakes the economy for a washing machine that needs monthly maintenance, or misconstrues the properties of your body for those of a compact disc player. Adam Smith himself made the analogy of the economy as a watch or a clock that once set in motion continues on its own. But I am certain that he did not quite think

of matters in these terms, that he looked at the economy in terms of organisms but lacked a framework to express it. For Smith understood the opacity of complex systems as well as the interdependencies, since he developed the notion of the “invisible hand.”

But alas, unlike Adam Smith, Plato did not quite get it. Promoting the well-known metaphor of the

ship of state,

he likens a state to a naval vessel, which, of course, requires the monitoring of a captain. He ultimately argues that the only men fit to be captain of this ship are philosopher kings, benevolent men with absolute power who have access to the Form of the Good. And once in a while one hears shouts of “who is governing us?” as if the world needs someone to govern it.

Social scientists use the term “equilibrium” to describe balance between opposing forces, say, supply and demand, so small disturbances or deviations in one direction, like those of a pendulum, would be countered with an adjustment in the opposite direction that would bring things back to stability. In short, this is thought to be the goal for an economy.

Looking deeper into what these social scientists want us to get into, such a goal can be death. For the complexity theorist Stuart Kaufman uses the idea of equilibrium to separate the two different worlds of

Table 2

.

For the nonorganic, noncomplex, say, an object on the table, equilibrium

(as traditionally defined)

happens in a state of inertia. So for something organic, equilibrium

(in that sense)

only happens with death.

Consider an example used by Kaufman: in your bathtub, a vortex starts forming and will keep going after that. Such type of situation is permanently “far from equilibrium”—and it looks like organisms and dynamic systems exist in such a state.

2

For them, a state of normalcy requires a certain degree of volatility, randomness, the continuous swapping of information, and stress, which explains the harm they may be subjected to when deprived of volatility.