Antifragile: Things That Gain from Disorder (37 page)

Read Antifragile: Things That Gain from Disorder Online

Authors: Nassim Nicholas Taleb

If you “have optionality,” you don’t have much need for what is commonly called intelligence, knowledge, insight, skills, and these complicated things that take place in our brain cells. For you don’t have to be right that often. All you need is the wisdom to

not do

unintelligent things to hurt yourself (some acts of omission) and recognize favorable outcomes when they occur. (The key is that your assessment doesn’t need to be made beforehand, only after the outcome.)

This property allowing us to be stupid, or, alternatively, allowing us to get more results than the knowledge may warrant, I will call the “philosopher’s stone” for now, or “convexity bias,” the result of a mathematical

property called Jensen’s inequality. The mechanics will be explained later, in

Book V

when we wax technical, but take for now that evolution can produce astonishingly sophisticated objects without intelligence, simply thanks to a combination of optionality and some type of a selection filter, plus some randomness, as we see next.

The great French biologist François Jacob introduced into science the notion of options (or option-like characteristics) in natural systems, thanks to trial and error, under a variant called

bricolage

in French. Bricolage is a form of trial and error close to

tweaking,

trying to make do with what you’ve got by recycling pieces that would be otherwise wasted.

Jacob argued that even within the womb, nature knows how to select: about half of all embryos undergo a spontaneous abortion—easier to do so than design the perfect baby by blueprint. Nature simply keeps what it likes if it meets its standards or does a California-style “fail early”—it has an option and uses it. Nature understands optionality effects vastly better than humans, and certainly better than Aristotle.

Nature is all about the exploitation of optionality; it illustrates how optionality is a substitute for intelligence.

2

Let us call trial and error

tinkering

when it presents small errors and large gains. Convexity, a more precise description of such positive asymmetry, will be explained in a bit of depth in

Chapter 18

.

3

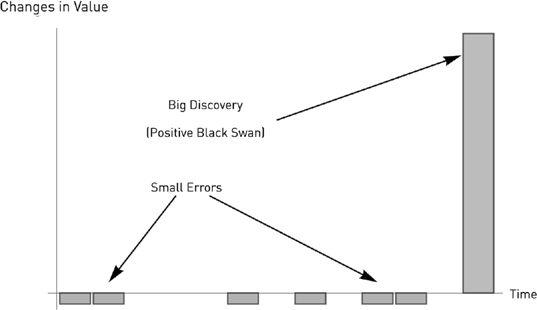

The graph in

Figure 7

best illustrates the idea present in California, and voiced by Steve Jobs at a famous speech: “Stay hungry, stay foolish.” He probably meant “Be crazy but retain the rationality of choosing the upper bound when you see it.” Any trial and error can be seen as the expression of an option, so long as one is capable of identifying a favorable result and exploiting it, as we see next.

FIGURE 6

. The mechanism of optionlike trial and error (the fail-fast model), a.k.a. convex tinkering. Low-cost mistakes, with known maximum losses, and large potential payoff (unbounded). A central feature of positive Black Swans: the gains are unbounded (unlike a lottery ticket), or, rather, with an unknown limit; but the losses from errors are limited and known.

To crystallize, take this description of an option:

Option = asymmetry + rationality

The rationality part lies in keeping what is good and ditching the bad, knowing to take the profits. As we saw, nature has a filter to keep the good baby and get rid of the bad. The difference between the antifragile and the fragile lies there. The fragile has no option. But the antifragile needs to select what’s best—the best option.

It is worth insisting that the most wonderful attribute of nature is the rationality with which it selects its options and picks the best for itself—thanks to the testing process involved in evolution. Unlike the researcher afraid of doing something different, it sees an option—the asymmetry—when there is one. So it ratchets up—biological systems get locked in a state that is better than the previous one, the path-dependent property I mentioned earlier. In trial and error, the rationality consists in not rejecting something that is markedly better than what you had before.

As I said, in business, people pay for the option when it is identified and mapped in a contract, so explicit options tend to be expensive to purchase, much like insurance contracts. They are often overhyped. But because of the domain dependence of our minds, we don’t recognize it in other places, where these options tend to remain underpriced or not priced at all.

I learned about the asymmetry of the option in class at the Wharton School, in the lecture on financial options that determined my career, and immediately realized that the professor did not himself see the implications. Simply, he did not understand nonlinearities and the fact that the optionality came from some asymmetry! Domain dependence: he missed it in places where the textbook did not point to the asymmetry—he understood optionality mathematically, but not really outside the equation. He did not think of trial and error as options. He did not think of model error as negative options. And, thirty years later, little has changed in the understanding of the asymmetries by many who, ironically, teach the subject of options.

4

An option hides where we don’t want it to hide. I will repeat that options benefit from variability, but also from situations in which errors carry small costs. So these errors are like options—in the long run, happy errors bring gains, unhappy errors bring losses. That is exactly what Fat Tony was taking advantage of: certain models can have only unhappy errors, particularly derivatives models and other fragilizing situations.

What also struck me was the option blindness of us humans and intellectuals. These options were, as we will see in the next chapter, out there in plain sight.

Indeed, in plain sight.

One day, my friend Anthony Glickman, a rabbi and Talmudic scholar turned option trader, then turned again rabbi and Talmudic scholar (so far), after one of these conversations about how this optionality applies to everything around us, perhaps after one of my tirades on Stoicism, calmly announced: “Life is long gamma.” (To repeat, in the jargon, “long” means “benefits from” and “short” “hurt by,” and “gamma” is a name for the nonlinearity of options, so “long gamma” means “benefits from volatility and variability.” Anthony even had as his mail address “@longgamma.com.”)

There is an ample academic literature trying to convince us that options are not rational to own because

some

options are overpriced, and they are deemed overpriced according to business school methods of computing risks that do not take into account the possibility of rare events. Further, researchers invoke something called the “long shot bias” or lottery effects by which people stretch themselves and overpay for these long shots in casinos and in gambling situations. These results, of course, are charlatanism dressed in the garb of science, with non–risk takers who, Triffat-style, when they want to think about risk, only think of casinos. As in other treatments of uncertainty by economists, these are marred with mistaking the randomness of life for the well-tractable one of the casinos, what I call the “ludic fallacy” (after

ludes,

which means “games” in Latin)—the mistake we saw made by the blackjack fellow of

Chapter 7

. In fact, criticizing all bets on rare events based on the fact that lottery tickets are overpriced is as foolish as criticizing all risk taking on grounds that casinos make money in the long run from

gamblers, forgetting that we are here because of risk taking

outside

the casinos. Further, casino bets and lottery tickets also have a known maximum upside—in real life, the sky is often the limit, and the difference between the two cases can be significant.

Risk taking

ain’t

gambling, and optionality

ain’t

lottery tickets.

In addition, these arguments about “long shots” are ludicrously cherry-picked. If you list the businesses that have generated the most wealth in history, you would see that they all have optionality. There is unfortunately the optionality of people stealing options from others and from the taxpayer (as we will see in the ethical section in

Book VII

), such as CEOs of companies with upside and no downside to themselves. But the largest generators of wealth in America historically have been, first, real estate (investors have the option at the expense of the banks), and, second, technology (which relies almost completely on trial and error). Further, businesses with negative optionality (that is, the opposite of having optionality) such as banking have had a horrible performance through history: banks lose periodically every penny made in their history thanks to blowups.

But these are all dwarfed by the role of optionality in the two evolutions: natural and scientific-technological, the latter of which we will examine in

Book IV

.

Even political systems follow a form of rational tinkering, when people are rational hence take the better option: the Romans got their political system by tinkering, not by “reason.” Polybius in his

Histories

compares the Greek legislator Lycurgus, who constructed his political system while “untaught by adversity,” to the more experiential Romans, who, a few centuries later, “have not reached it by

any process of reasoning

[emphasis mine], but by the discipline of many struggles and troubles, and always choosing the best by the light of the experience gained in disaster.”

Let me summarize. In

Chapter 10

we saw the foundational asymmetry as embedded in Seneca’s ideas: more upside than downside and vice versa. This chapter refined the point and presented a manifestation of

such asymmetry in the form of an option, by which one can take the upside if one likes, but without the downside. An option is the weapon of antifragility.

The other point of the chapter and

Book IV

is that the option is a substitute for knowledge—actually I don’t quite understand what sterile knowledge is, since it is necessarily vague and sterile. So I make the bold speculation that many things we think are derived by skill come largely from options, but well-used options, much like Thales’ situation—and much like nature—rather than from what we claim to be understanding.

The implication is nontrivial. For if you think that education causes wealth, rather than being a result of wealth, or that intelligent actions and discoveries are the result of intelligent ideas, you will be in for a surprise. Let us see what kind of surprise.

1

I suppose that the main benefit of being rich (over just being independent) is to be able to despise rich people (a good concentration of whom you find in glitzy ski resorts) without any sour grapes. It is even sweeter when these farts don’t know that you are richer than they are.

2

We will use nature as a model to show how its operational outperformance arises from optionality rather than intelligence—but let us not fall for the naturalistic fallacy: ethical rules do not have to spring from optionality.

3

Everyone talks about luck and about trial and error, but it has led to so little difference. Why? Because it is not about luck, but about optionality. By definition luck cannot be exploited; trial and error can lead to errors. Optionality is about getting the upper half of luck.

4

I usually hesitate to discuss my career in options, as I worry that the reader will associate the idea with finance rather than the more scientific applications. I go ballistic when I use technical insights derived from derivatives and people mistake it for a financial discussion—these are only techniques, portable techniques, very portable techniques, for Baal’s sake!