Antifragile: Things That Gain from Disorder (36 page)

Read Antifragile: Things That Gain from Disorder Online

Authors: Nassim Nicholas Taleb

Superior knowledge?

Thales put himself in a position to take advantage of his

lack

of knowledge—and the secret property of the asymmetry. The key to our message about this upside-downside asymmetry is that he did not need to understand too much the messages from the stars.

Simply, he had a contract that is the archetype of what an asymmetry is, perhaps the only explicit asymmetry you can find in its purest form. It is an option, “the right but not the obligation” for the buyer and, of course, “the obligation but not the right” for the other party, called the seller. Thales had the right—but not the obligation—to use the olive presses in case there would be a surge in demand; the other party had the obligation, not the right. Thales paid a small price for that privilege, with a limited loss and large possible outcome. That was the very first option on record.

The option is an agent of antifragility.

The olive press episode took place about six hundred years before Seneca’s writings on his tables with ivory legs, and three hundred years before Aristotle.

The formula in

Chapter 10

was:

antifragility

equals

more to gain than to lose

equals

more upside than downside

equals

asymmetry (unfavorable)

equals

likes volatility

. And if you make more when you are right than you are hurt when you are wrong, then you will benefit, in the long run, from volatility (and the reverse). You are only harmed if you repeatedly pay too much for the option. But in this case Thales patently got a good deal—and we will see in the rest of

Book IV

that we don’t pay for the options given to us by nature and technological innovation. Financial options may be expensive because people know they are options and

someone

is selling them and charging a price—but most interesting options are free, or at the worst, cheap.

Centrally, we just don’t need to

know

what’s going on when we buy cheaply—when we have the asymmetry working for us. But this property goes beyond buying cheaply: we do not need to understand things when we have some edge. And the edge from optionality is in the larger payoff when you are right, which makes it unnecessary to be right too often.

The option I am talking about is no different from what we call options in daily life—the vacation resort with the most options is more likely to provide you with the activity that satisfies your tastes, and the one with the narrowest choices is likely to fail. So you need

less information,

that is, less knowledge, about the resort with broader options.

There are other hidden options in our story of Thales. Financial independence, when used intelligently, can make you robust; it gives you options and allows you to make the right choices. Freedom is the ultimate option.

Further, you will never get to know yourself—your real preferences—unless you face options and choices. Recall that the volatility of life helps provide information to us about others, but also about ourselves. Plenty of people are poor against their initial wish and only become robust by spinning a story that it was their choice to be poor—as if they had the

option. Some are genuine; many don’t really have the option—they constructed it. Sour grapes—as in Aesop’s fable—is when someone convinces himself that the grapes he cannot reach are sour. The essayist Michel de Montaigne sees the Thales episode as a story of immunity to sour grapes: you need to know whether you

do not like

the pursuit of money and wealth because you genuinely do not like it, or because you are rationalizing your inability to be successful at it with the argument that wealth is not a good thing because it is bad for one’s digestive system or disturbing for one’s sleep or other such arguments. So the episode enlightened Thales about his own choices in life—how genuine his pursuit of philosophy was. He had other

options.

And, it is worth repeating, options, any options, by allowing you more upside than downside, are vectors of antifragility.

1

Thales, by funding his own philosophy, became his own Maecenas, perhaps the highest rank one can attain: being both independent and intellectually productive. He now had even more

options.

He did not have to tell others—those funding him—where he was going, because he himself perhaps didn’t even know where he was heading. Thanks to the power of options, he didn’t have to.

The next few vignettes will help us go deeper into the notion of

optionality

—the property of option-like payoffs and option-like situations.

It is Saturday afternoon in London. I am coping with a major source of stress: where to go tonight. I am fond of the brand of the unexpected one finds at parties (going to parties has optionality, perhaps the best advice for someone who wants to benefit from uncertainty with low downside). My fear of eating alone in a restaurant while rereading the same passage of Cicero’s

Tusculan Discussions

that, thanks to its pocket-fitting size, I have been carrying for a decade (and reading about three and a half pages per year) was alleviated by a telephone call. Someone, not a close friend, upon hearing that I was in town, invited me to a gathering in

Kensington, but somehow did not ask me to commit, with “drop by if you want.” Going to the party is better than eating alone with Cicero’s

Tusculan Discussions,

but these are not very interesting people (many are involved in the City, and people employed in financial institutions are rarely interesting and even more rarely likable) and I know I can do better, but I am not certain to be able to do so. So I can call around: if I can do better than the Kensington party, with, say, a dinner with any of my real friends, I would do that. Otherwise I would take a black taxi to Kensington. I have an

option,

not an obligation. It came at no cost since I did not even solicit it. So I have a small, nay, nonexistent, downside, a big upside.

This is a free option because there is no real cost to the privilege.

Second example: assume you are the official tenant of a rent-controlled apartment in New York City, with, of course, wall-to-wall bookshelves. You have the

option

of staying in it as long as you wish, but no obligation to do so. Should you decide to move to Ulan Bator, Mongolia, and start a new life there, you can simply notify the landlord a certain number of days in advance, and thank you goodbye. Otherwise, the landlord is obligated to let you live there somewhat permanently, at a predictable rent. Should rents in town increase enormously, and real estate experience a bubble-like explosion, you are largely protected. On the other hand, should rents collapse, you can easily switch apartments and reduce your monthly payments—or even buy a new apartment and get a mortgage with lower monthly payments.

So consider the asymmetry. You benefit from lower rents, but are not hurt by higher ones. How? Because here again, you have an option, not an obligation. In a way, uncertainty increases the worth of such privilege. Should you face a high degree of uncertainty about future outcomes, with possible huge decreases in real estate value, or huge possible increases in them, your option would become more valuable. The more uncertainty, the more valuable the option.

Again, this is an embedded option, hidden as there is no cost to the privilege.

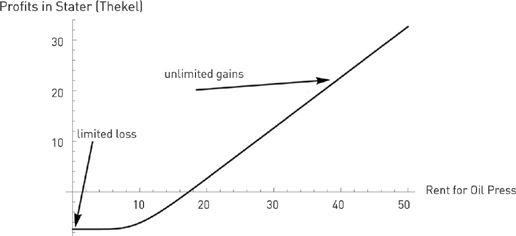

Let us examine once again the asymmetry of Thales—along with that of any option. In

Figure 5

, the horizontal axis represents the rent, the vertical axis the corresponding profits in thekels.

Figure 5

shows the asymmetry: in this situation, the payoff is larger one way (if you are right, you “earn big time”) than the other (if you are wrong, you “lose small”).

FIGURE 5

. Thales’ antifragility. He pays little to get a huge potential. We can see the asymmetry between upside and downside.

The vertical axis in

Figure 5

represents a function of the rent for oil presses (the payoff from the option). All the reader needs to note from the picture is the nonlinearity (that is, the asymmetry, with more upside than downside; asymmetry is a form of nonlinearity).

One property of the option: it does not care about the average outcome, only the favorable ones (since the downside doesn’t count beyond a certain point). Authors, artists, and even philosophers are much better off having a very small number of fanatics behind them than a large number of people who appreciate their work. The number of persons who dislike the work don’t count—there is no such thing as the

opposite

of buying your book, or the equivalent of losing points in a soccer game, and this absence of negative domain for book sales provides the author with a measure of optionality.

Further, it helps when supporters are both enthusiastic and influential.

Wittgenstein, for instance, was largely considered a lunatic, a strange bird, or just a b***t operator by those whose opinion didn’t count (he had almost no publications to his name). But he had a small number of cultlike followers, and some, such as Bertrand Russell and J. M. Keynes, were massively influential.

Beyond books, consider this simple heuristic: your work and ideas, whether in politics, the arts, or other domains, are antifragile if, instead of having one hundred percent of the people finding your mission acceptable or mildly commendable, you are better off having a high percentage of people disliking you and your message (even intensely), combined with a low percentage of extremely loyal and enthusiastic supporters. Options like dispersion of outcomes and don’t care about the average too much.

Another business that does not care about the average but rather the dispersion around the average is the luxury goods industry—jewelry, watches, art, expensive apartments in fancy locations, expensive collector wines, gourmet farm-raised probiotic dog food, etc. Such businesses only care about the pool of funds available to the very rich. If the population in the Western world had an average income of fifty thousand dollars, with no inequality at all, luxury goods sellers would not survive. But if the average stays the same but with a high degree of inequality, with some incomes higher than two million dollars, and potentially some incomes higher than ten million, then the business has plenty of customers—even if such high incomes are offset by masses of people with lower incomes. The “tails” of the distribution on the higher end of the income brackets, the extreme, are much more determined by changes in inequality than changes in the average. It gains from dispersion, hence is antifragile. This explains the bubble in real estate prices in Central London, determined by inequality in Russia and the Arabian Gulf and totally independent of the real estate dynamics in Britain. Some apartments, those for the very rich, sell for twenty times the average per square foot of a building a few blocks away.

Harvard’s former president Larry Summers got in trouble (clumsily) explaining a version of the point and lost his job in the aftermath of the uproar. He was trying to say that males and females have equal intelligence, but the male population has more variations and dispersion (hence volatility), with more highly unintelligent men, and more highly intelligent ones. For Summers, this explained why men were overrepresented

in the scientific and intellectual community (and also why men were overrepresented in jails or failures). The number of successful scientists depends on the “tails,” the extremes, rather than the average. Just as an option does not care about the adverse outcomes, or an author does not care about the haters.

No one at present dares to state the obvious: growth in society may not come from raising the average the Asian way, but from increasing the number of people in the “tails,” that small, very small number of risk takers crazy enough to have ideas of their own, those endowed with that very rare ability called imagination, that rarer quality called courage, and who make things happen.

Now some philosophy. As we saw with the exposition of the Black Swan problem earlier in

Chapter 8

, the decision maker focuses on the payoff, the consequence of the actions (hence includes asymmetries and nonlinear effects). The Aristotelian focuses on being right and wrong—in other words, raw logic. They intersect less often than you think.

Aristotle made the mistake of thinking that knowledge about the event (future crop, or price of the rent for oil presses, what we showed on the horizontal axis) and making profits out of it (vertical) are the same thing. And here, because of asymmetry, the two are not, as is obvious in the graph. As Fat Tony will assert in

Chapter 14

, “they are not the same thing” (pronounced “ting”).