April Queen (15 page)

Authors: Douglas Boyd

Nor was the emperor of Byzantium a mere western monarch, prepared to sally out and welcome the pilgrim king of the Franks as a brother. Remaining prudently in the Boukoleon palace overlooking the Bosporus, he sent minions to order the foreigners to make camp at the tips of the Golden Horn. If such a welcome was less warm than the promises at Ratisbon, Louis was reassured when a delegation of nobles bearing gifts arrived with an invitation for him and a few companions to enter the gates and wait upon the imperial pleasure within.

Odo’s chronicle was essentially hagiographic, to show his king as a great leader. He skates over the welcome to describe Constantinople as ‘the glory of the Greeks’.

Rich in fame, richer yet in wealth, the city is shaped like a triangular sail and hemmed in on two sides by the sea. Approaching the city, we had the Arm of St George on our right; on our left, an estuary four miles long.

The [landward] side of the city is fortified by towers and a double wall that extends for nearly two miles from the sea to the Blachernae palace. Within the walls are cultivated fields and market gardens that provide vegetables for the citizens. Subterranean conduits flow into the city under the walls, bringing abundant fresh water.

The city is rather squalid and foetid [and] the rich build their houses overhanging the streets, making these dark and dirty places for travellers and the poor, where murders and robberies occur as well as other sordid crimes which love the dark. Constantinople excels in

everything, surpassing other cities in wealth, but also in vice. It has many churches which, although not comparable with Santa Sophia for size, are beautified with numerous venerable relics of the saints.

6

Odo’s account is relatively unprejudiced. If he holds the Greeks’ generous hospitality to be proof that their intentions were less than honest, he understands them keeping city gates closed against the drunken French rabble who had burned many houses and cut down olive trees for firewood. The punishments frequently witnessed by Eleanor and her ladies – executions and amputations of ears, hands and feet ordered by Louis – did little to reduce these excesses.

The opulent emperor and the king in unadorned pilgrim’s tunic met accompanied by bodyguards and interpreters outside the Boukoulion imperial palace. After exchanging the kiss of peace, they moved inside for the long-drawn-out diplomatic courtesies of the East, Comnenus offering the Blachernae Palace within the outer walls for the accommodation of Louis and his nobles so that not too many of them would ever be within the inner city at any one time. The rest of the French were to sleep under canvas or in the open for the duration of their stay.

Of the Blachernae, Odo writes:

The palace affords its residents the pleasure of gazing on sea, countryside and town. The exterior of the palace is extremely beautiful and the interior excels all I can say. The walls are of gold and various colours and the floor is paved with mosaics. I do not know whether the subtlety of the craftsmanship or the preciousness of the materials gives it the greater beauty or value.

7

The sumptuousness of Comnenus’ guest accommodation was an eye-opener to Eleanor after her quarters in the dilapidated palace on the Ile de la Cité. For the first time in their lives the Amazons enjoyed running water, brought into the city by the aqueduct of Valens and distributed through a system of cisterns. Another luxury for them were the flushing toilets. Thanks to Roman sewerage, both surface run-off and ‘brown’ water were effortlessly and comparatively hygienically disposed of into the sea.

The Blachernae was a warren of several hundred audience rooms, bedrooms, cloistered harems, ornate chapels and busy kitchens. Between the outer wall of Theodosius and Constantine’s inner wall, it was on the scale of, and in the same haphazard layout as, the Topkapi Palace.

But whereas Topkapi is now bare of figurative art offensive to the Muslim eye, the Blachernae was then a treasure house of gilt and mosaic, tapestry and fresco, crystal and marble, filled with beauty from the days of the city’s ancient glory and trophies from all over the Roman Empire, from Baghdad and Mosul and India and far-off Cathay.

Within the palace precincts was a deer park stocked with game for the hunt – a pleasure forbidden by their oath to the crusaders – as well as landscaped gardens from whose shady pavilions Eleanor’s ladies could enjoy the view across the Golden Horn. From the Blachernae, they looked down on the Philopation, another palace in a park outside the walls, which had been equally luxurious before being vandalised by the German contingent recently accommodated there.

On arrival, Louis dictated to Odo a letter to Suger, praising God for bringing them safely through the dangers and hardships of the journey so far. Like so many commanders-in-chief, he seemed surprised that expenditure was way over budget. The letter ended, as they all did, with an urgent plea for more money.

8

Once she had explored the marvels of the palace the 25-year-old queen and her ladies could explore the city itself. The back streets may have been narrow, dark and gloomy, as Odo said, but so were most of the streets in Paris, whereas Constantinople’s main thorough-fare had a grandeur unknown in Europe’s capitals. From the emperor’s palace a long arcaded street ran west, linking forums and marketplaces adorned with monuments and fountains and bordered by the domes and minarets of a hundred churches. Sumptuously decorated, they enshrined relics, many brought back by Constantine’s mother Saint Helena from her visit to the Holy Land in the third century. These included alleged bones of several disciples, the True Cross from Golgotha and a thorn from the Crown of Thorns.

But the greatest marvel was the glorious Hagia Sophia or Church of the Holy Wisdom. Built six centuries earlier to replace Constantine’s basilica, which had been destroyed in a riot, and completed in less than six years, Constantinople’s architectural masterpiece was at the time of Eleanor’s visit more than an object of beauty, with its columns of finest marble to delight the senses of sight and touch and its walls and roof decorated entirely in rich mosaics that have now disappeared.

It was also a technical triumph by Antithemius of Tralles and Isidorus of Miletus. By brilliant use of the Persian squinch and the innovative Syrian pendentive – among the first devices that deflected vertical thrust and avoided unsightly masses of load-bearing masonry – the two architects of genius had solved the apparently impossible

challenge of translating a square ground plan into a load-bearing circle flanked by two semicircles on which the immense and perfectly circular dome and its two flanking semi-domes rested in lofty eastern grandeur, so different from the vertical Gothic lines of Suger’s basilica at St Denis and more breathtaking by far than any Romanesque church. To Louis, all was symbolic: the square represented man’s creation, the circle above the perfection of Heaven.

When he was invited to Mass in Hagia Sophia, eyes and ears were equally pleasured. The polyphony and counterpoint of the Greek litany sung by disciplined choirs of

castrati

echoing from the glittering dome outdid anything in contemporary western music. With the emperor and his guests surrounded by ranks of functionaries and accorded obsequious oriental respect, there was no need for Louis to beat a passage for himself through the common mob with a staff, as he had been obliged to do at the consecration of St Denis. The servility of the imperial eunuchs and slaves contrasted with the casual attitude of Eleanor’s servants. Even the satraps of Byzantium humbled themselves before the emperor and spoke in his presence only when he told them to. It was all most unlike the physical jostling and constant challenges to her authority which were the norm among her own insubordinate vassals.

On the Greek Orthodox feast of Louis’ patron saint Dionysius the Areopagite, Manuel sent to the Blachernae a chorus of priests chosen for their superb voices. Bearing crosses and lit candles, they performed for Eleanor and Louis an exquisitely choreographed sung Mass in the saint’s own language. It was a most thoughtful gift for a king who dressed like a pilgrim and spent in venerating the relics of the saints and in fasting the time he should have devoted to preparing for departure before the approach of autumn.

For Eleanor’s ladies with money to enjoy the pleasure of shopping, the souks of the city and the warehouses of the Italian merchants across the water in Galata provided the more sensuous pleasures of perfumes, jewellery and works of art in silver and gold, glass from Hebron and Antioch, carved ivory from India and Africa. There was fine metalwork of a quality unobtainable in the West, carpets from Persia and Afghanistan, and sumptuous materials including the finest silk from China, linen from Egypt, brocades from Tripoli, Baghdad and even the Turkish capital of Mosul, which had been fabled Nineveh in the time of Assyrian greatness. As entertainments, there were horse races, tournaments and public games in Constantine’s hippodrome adjacent to the imperial palace, which she attended with Comnenus’ European wife. The empress and the queen had much in common: they were

young and beautiful, each had been married for political reasons to a husband who spoke another language and sent to live in what was, to her, a foreign and friendless court.

But an enormous gulf of culture separated the Byzantines from most of their unwanted French guests. Eleanor had many times ridden past the imposing ruins of the Roman baths at Chassenon on the main road from Saintes to Lyon, but in Constantinople the public baths were still functioning and well patronised, as were the scores of

hammams

.

9

In Europe

alousia

or not washing was considered a sign of holiness. The Byzantines abhorred the stink of the unwashed French and the smell of their breath, due to their habit of chewing raw garlic as a prophylactic.

Although the Roman amphitheatre with over thirty rows of banked seating held no more spectators than had in their heyday those at Bordeaux and Saintes with which Eleanor was familiar, those were ruins used as quarries for their marble and dressed limestone. In what had been the capital of Rome’s eastern empire, the public still gazed up at life-size and gigantic statues of men and animals atop the walls, some of them automata that moved or roared or appeared to sing for the crowd’s amusement. Like Caesar’s entourage at the games in Rome, Comnenus and his guests were not hustled by the crowd in the

vomitoria

– the claustrophobic corridors by which the common people gained their seats – but moved sedately through a separate network of private passages to the royal lodge, in which they presided over and were part of the spectacle.

10

Invited to dine with the emperor in the Boukoleon, a palace even more luxurious than their own lodgings in the Blachernae, the French royal party did not sit, but reclined on couches in the old Roman fashion to be regaled with delicacies of which their palates could not distinguish the subtly combined ingredients. In late summer there was still snow a-plenty from the Caucasus to chill the sherbets and cool the wine, served in precious glasses. Spices unknown in Europe teased the palate, as new and exciting harmonies teased the ear, vying with the plashing of scented fountains and the singing of golden birds in a mechanical tree. Musicians, dancing girls and acrobats entertained them during the banquet.

The purpose of all this oriental hospitality was to delay the French until they could not possibly join up with Conrad’s army to defeat the Turks and turn back to Constantinople in force. If Eleanor and the ladies were happy to continue enjoying the delights of the most civilised city of the day, Thierry Galeran and Louis’ other military advisers were chafing at the inactivity because they knew how

important it would be to cross the high mountain passes of what is now southern Turkey before the first snows of winter.

After Louis’ uncle the Count of Maurienne arrived with a smaller contingent that had travelled via Italy, the king’s last letter to Suger before departure echoed the first:

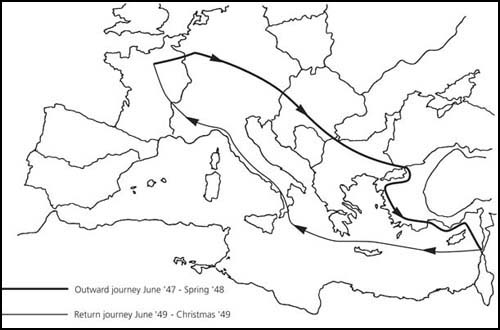

send more money

. The expedition was already way over budget, but the army could not move through a hostile semi-desert country without adequate supplies. They crossed the Bosporus into Asia Minor about 16 October 1147 and followed the line taken by the modern motorway along the Izmit inlet to Nicomedia.

From there, three possible routes diverged, the shortest being the age-old caravan trail from Constantinople to Tarsus – where St Paul was born – and onward to Aleppo and Edessa. Odo spells out the advantages and disadvantages of each route:

The left-hand road is the shortest. However, after twelve days it reaches Konya, the Sultan’s capital, which is a very noble city. Five days beyond, this road reaches the land of the Franks. An army strong in faith and numbers could fight its way through, except in winter when the mountains are snow-covered. The right-hand road is less dangerous and better-supplied, but three times as long, running along

the indented littoral with rivers and torrents in winter as dangerous as the Turks and the snow on the other road. The middle road is a compromise between the other two, longer but safer than the left route, and shorter than the right route, but ill-provided with food.

Therefore the Germans split into two parties. Many risked setting out with the Emperor via Konya, the others turning right under his brother. The middle road was chosen by us.

11