Arnold Weinstein - A Scream Goes Through The House (29 page)

Read Arnold Weinstein - A Scream Goes Through The House Online

Authors: What Literature Teaches Us About Life [HTML]

It has been suggested that the entire analytic project in Hawthorne is sexually charged, so that the intimacy of "knowing" another diagnosti-cally becomes an ersatz, even a version of erotic conquest. Readers have often felt that the central love relation between Hester and Dimmesdale remains either abstracted or hidden from view in the novel, a crucial prior event, yes, but never actualized in the prose; I'd argue that the real heat and steaminess of

The Scarlet Letter

are to be found in the Chillingworth-Dimmesdale pas de deux, inasmuch as the

penetration

of the other is hot stuff indeed. Dimmesdale swears to Hester that such penetration is far more sinful than their own sexual liaison: " 'He has vi-

olated, in cold blood, the sanctity of a human heart. Thou and I, Hester, never did so!' " (140).

Doctors force their way inside us; but, then, writers do too, and no amount of "satanizing" on Hawthorne's part will blind us to the fact that the doctor's quest is imbued with a kind of hunger and energy that is fueling the entire narrative. Chillingworth is doing Hawthorne's job.

One of the most fascinating literary figures in this regard is Georg Biichner, whose tragically brief career as playwright, lecturer in natural history, and political revolutionary in Germany in the 1830s is entirely cued to the irresistible and inhuman power of scientific analysis. I have already discussed the animality theme in Biichner, but now I want to go further: his sovereign critique of political action (he understands the link between materialism and fanaticism, as he ponders ways to make peasants politically aware, evidence of which we find in his correspondence) stems from the same cold and insatiable curiosity that fuels his groundbreaking doctoral research on the cranial nerves of frogs (research so brilliant that it immediately garnered him a university professorship), and it is just this constellation of analytical intelligence-as-power that is put on trial in his magnificent play,

Woyzeck.

Biichner puts all the pieces of his life together here, as we watch the antics of the pathetic subaltern, Woyzeck,

armerKerl

(poor slob) if there ever was one, hounded and mocked by his superiors, most unforgettably exemplified in the machinations of the play's Doctor, who does human experiments with Woyzeck, subjects him to a diet of peas, has him palpated by his medical students, describes his heart-wrenching anguish in the brutal clinical terminology of science, as an affair of pulse rate and heavy breathing. For us, Woyzeck is quasi-crucified; for the Doctor, Woyzeck may be the makings of a professional article. "What makes Woyzeck tick?" is this play's subtext, and whereas we hear in this early proletarian drama the ticking of a time bomb, it is clear that Biichner himself shares the experimental obsessions of his doctor, even though he measures their inhumanity and reductiveness. Woyzeck is

reified in front of our eyes, turned into case study, an object of knowledge and horrible exposure.

If Buchner is primitive and brutal in his assault, other writers can be subtle and decorous. No more frightening example of "death by exposure" exists than that of the boy/child Miles in Henry James's novella

The Turn of the Screw,

where the governess relentlessly stalks the little boy in order to find out what he is concealing, and this drama of opening up the other appropriately climaxes in the death of the child. James alters the course of modern fiction by fashioning a narrative theory and repertory that consist, largely, of one quivering consciousness trying to make out what is happening around it, usually found in those other consciousnesses it must deal with. It is hard to convey, in my critical prose, just how decorous yet obscene this kind of thing can be: the governess realizes that the child's lies (if they are that) make up her truth (if it is that), yielding a dialectic of hounding and hunger that moves increasingly from the merely verbal to the corporeal. Take a step back from this decorous story, and you see an older woman systematically closing in on a young boy (everyone else is eventually removed from the house), hot after his secrets, pressing him, more and more urgent in her campaign. One actually feels the awful deliciousness of the contest as she moves in for the kill:

The face that was close to mine was as white as the face against the glass [the "ghost" that

she

sees, but whose "status" has been the subject of almost a century of critical debate], and out of it presently came a sound, not low nor weak, but as if from much further away, that I drank like a waft of fragrance.

"Yes—I took it." [the child's "confession" of his secret] At this, with a moan of joy, I enfolded, I drew him close; and while I held him to my breast, where I could feel in the sudden fever of his little body the tremendous pulse of his little heart, I kept my eyes on the thing at the window and saw it move and shift its posture. (85)

The libidinal heat here is overwhelming—the reader measures the almost vampirish feelings of the governess (that "waft of fragrance" she drinks in)—and James has given us a virtually medical notation of the child's condition: a sudden fever, a tremendous pulse. And why not: folded as he is in the arms of this hungry woman, his entire system tells him he is in trouble.

There are few outright detectives in James, but no one surpasses him in sleuthing prowess, and the elegance and fastidiousness of these performances (for they now seem almost operatic to today's readers) convey a wonderful mix of the licit and the illicit, of such ferreting out as the social game par excellence, as well as a test of both intellect and power. The libidinal underpinnings of such probing and digging are unmistakable in both Hawthorne and James, and no reader can miss the sexual hunger that accompanies the epistemological challenge at hand. No less unmistakable, however, is the parallel between this theme of diseased detection and the emerging view of fiction itself, as if storytelling were inseparable from these acts of violation and vampirism, as if the viewing of the human being in terms of signs and symptoms were at once the origin and end of narrative: origin because the speculative, interpretive work of decoding the signs, the hermeneutic drive, is the very pulse of storytelling; and end because the final revelation can kill as well as close.

Nineteenth-century literature is brimming over with comparable scenarios. The heated confections of Dickens and Dostoevsky and the genteel parlor romances like Austen's have been mentioned, but outright teasers like Melville's story "Bardeby the Scrivener" also derive much of their energy from this source. Ibsen's entire enterprise revolves around the exposure of hidden secrets and dirty laundry in the affairs of his Norwegian burghers, but with each successive play he comes to understand the sanctity of secrets, the vulnerability of the exposed human subject. I find Ibsen especially provocative in this regard, inasmuch as the diagnostic imperative is initially seen as the key to his entire dramatic agenda; audiences would flock to see his plays in order to discover what he was going to unveil, unmask, diagnose "this time."

Yet, soon enough in Ibsen's plays, the diagnostician, the man who ferrets out lies and secrets, comes to be seen as monster, not hero, and a sick monster to boot, so that the very urge to get inside gets increasingly understood as at once exploitative and also a cover for one's own neurotic needs. Moreover, as dramatist, Ibsen gradually shifts his focus from secrets themselves to the complex dance of those with secrets, a dance he wonderfully terms the

life-lie,

expressing the view that our dodges and illusions and fantasies are the fuels that get us through life. The brilliance of Ibsen's late dramaturgy derives from showing how we are all the walking wounded, how all of us are using crutches of some sort in order to move at all. In this Ibsen becomes remarkably postdiagnostic, in a way that mirrors the dilemma of modern medicine: not so much what our ailments are, but how we manage to live with them is what we need to know. In the hands of Ibsen, just as in the clinical tales of Oliver Sacks, we come to see just how breathtaking these antics can be.

Ibsen's mad Scandinavian confrere, Strindberg, offers us in

The Ghost Sonata,

his surrealist masterpiece of 1907, Western theater's most astounding send-up of diagnosis. Working with the trusty convention of roof lifting, of exposing what is hidden behind the walls of the prosperous bourgeoisie, Strindberg proceeds surgically to unmask the most diseased and incestuously intertwined group of people in the history of the theater. The great exposer, Hummel, is cast as a version of Thor, the god of war, with a special prowess in crashing through walls, penetrating secrets. Here is how Hummel undoes the Colonel (whose promissory notes he has already bought up):

COLONEL: Are you trying to run my house?

old man: Yes! Since I own everything here: furniture, curtains,

dinner service, linen . . . and other things! colonel: What other things?

old man: Everything! I own everything! It's all mine! colonel: Very well, it's all yours. But my family's coat of arms, and

my good name—they remain mine!

old man: No, not even those!

(pause)

You're not a nobleman.

colonel: How dare you?

old MAN:

(taking out a paper)

If you read this extract from the Book of Noble Families, you'll see that the name you bear died out a hundred years ago.

colonel:

(reading)

I've certainly heard such rumors, but the name I bear was my father's . . .

(reading)

It's true, you are right . . . I'm not a nobleman!—Not even that remains!—Then I'll take off my signet ring.—It too belongs to you . . . Here, take it!

old man:

(pocketing the ring)

Now we'll continue!—You're not a colonel either.

colonel: I'm not?

OLD man: No! You were a former temporary colonel in the American Volunteers, but when the army was reorganized after the Spanish-American War, all such ranks were abolished . . .

colonel: Is that true?

old man:

(reaching into his pocket)

Do you want to read about it?

colonel: No, it's not necessary! . . . Who are you, that you have the right to sit here and strip me naked like this?

old man: We'll see! But speaking about stripping . . . do you know who you really are?

colonel: Have you no sense of shame?

old man : Take off your wig and look at yourself in the mirror! Take out your false teeth too, and shave off your mustache! We'll have Bengtsson unlace your corset, and we'll see if a certain servant, Mr. XYZ, won't recognize himself: a man who was once a great sponger in a certain kitchen . . . (295-296)

There is something adrenaline filled and vaudevillian in Strindberg's handling of the exposure motif, as he cavalierly moves from false papers to false teeth, suggesting that the sleuthing diagnostic gaze operates on the order of PacMan, a voracious mouth that gobbles up everything it encounters, an X-ray machine that delights in shredding every surface it sees through.

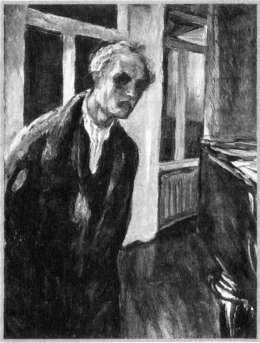

Self-Portrait (Night Wanderer),

Edvard Munch, 1923-1924.

The maniacal humor here suggests that the ever-so-serious mysteries confronted in Dickens, Ibsen, and company are now becoming the material for sitcoms. And yet, Strindberg's play is under the aegis of sickness and exhaustion: at the very beginning, the medical student (whom Hummel seeks to use in his revenge scenario) asks the ghostlike milkmaid to cleanse his eyes, eyes that are inflamed, eyes that he cannot touch because his hands have been touching the injured and the dead. We are hard put not to see the aging Strindberg here, a playwright whose eyes are inflamed by so much unmasking of filth and hypocrisy, so much horror. One senses a judgment being rendered on the diagnostic gaze itself, as if the capacity to read surfaces, to see what they conceal, to espy the human drama behind the facade, were something grueling, dirtying, finally unbearable.

I'll close this line of reasoning by noting one of Edvard Munch's later paintings,

Night Wanderer,

a self-portrait that seems to relate the horror of having been Edvard Munch, above all of having had Edvard Munch's

eyes

for an entire lifetime. This gaunt, precarious figure, backgrounded by windows giving on to the dark night, has black hollows for eyes, as if what he had seen had gradually eaten up his flesh, a kind of ocular leprosy as it were, offered here as occupational hazard for artists and diagnosticians. Hogarth's sadistic and cruel Tom Nero had his eye plucked out; Hawthorne's Dimmesdale is said (by some, as the savvy Hawthorne puts it) to have an

A

carved in his breast, and although the pious reading would ascribe this to the minister's guilt, I prefer to see it as the fleshly incision caused by Chillingworth's prying eye; Munch finishes our parade and suggests that peering into the mysteries and exposing what is hidden there exacts its toll in your own flesh.