Arnold Weinstein - A Scream Goes Through The House (30 page)

Read Arnold Weinstein - A Scream Goes Through The House Online

Authors: What Literature Teaches Us About Life [HTML]

PRESERVING SECRETS, REMAINING IMPENETRABLE

"If looks could kill," the popular expression goes, and it is instructive to reflect on just how damaging looking and being looked at can be. The Lord creates light in Genesis chapter one, but we must wait until Genesis chapter three, when the apple is eaten, before the human subject is endowed with vision—"Then the eyes of both were opened, and they knew that they were naked"—which then introduces both consciousness and shame into the world. The motif of the

evil eye

extends back to folktales and magic, but, often enough, it depicts prying, invading, exposing. Poe's famous short story "The Tell-Tale Heart" is presented initially as a gratuitous act of murder: "I loved the old man. He had never wronged me. He had never given me insult. For his gold I had no desire. I think it was his eye! yes, it was this! He had the eye of a vulture—a pale blue eye, with a film over it. Whenever it fell upon me, my blood ran cold; and so by degrees—very gradually—I made up my mind to take the life of the old man, and thus rid myself of the eye forever" (1951,244). Gratuitous? We do not need to be Dr. Freud to see that the action is di-

rected against the vulture eye, that the eye seems to be the organ of authority, spying, invasion, consciousness itself, and the speaker cannot bear it.

Ibsen's late play

Little Eyolf

(his greatest, in my view) features a dead child who lies at the bottom of the sea with his eyes open,

evil eyes,

indicting his parents forever. The brilliance of the play consists in the fact that this child has been an evil eye since infancy, when he was left unattended while his parents had furious sexual intercourse, resulting in the child's falling off the table and becoming lame, so that the child's prying eyes seem to haunt this marriage in its entirety, dooming both sexuality and peace. It's worth noting that Ibsen is quite modern in positing the

child

as invading eye, as diagnostic judge for his elders—quite reversing, say, James's treatment of the child in

The Turn of the Screw,

or indeed our familiar (and pious) assumption that children are victims rather than victimizers—thereby giving us an eerie feeling that adults are even more haunted by the Pauline prophecy of being "seen and known" than children are. And why shouldn't they be? They surely have more to hide, as Ibsen well knew. I quite realize I am implying that the nuclear family is a den of espionage, but I suspect that most parents will know what I am talking about.

Privacy, social historians have told us, is not a timeless, universal concept, but rather the construct of particular social arrangements, located within the dynamics and habits of the Early Modern family. There was, we gather, a time when folks had less

pudeur,

were less squeamish about the body and about sexuality, were more on view all the time. But Genesis chapter three also tells us about privacy and exposure, about the cost of being seen. Even Hamlet resists being seen and "played upon," as he informs Rosencrantz and Guildenstern: "You would play upon me, you would seem to know my stops, you would pluck out the heart of my mystery, you would sound me from my lowest note to the top of my compass; and there is much music, excellent voice, in this little organ, yet cannot you make it speak. 'Sblood, do you think I am eas-

ier to be played on than a pipe? Call me what instrument you will, though you can fret me, you cannot play upon me" (

III.ii.332—

338).

Of particular interest, from this perspective, are those figures who refuse to be seen, who remain staunchly closed against the prying eyes of seers and tellers. Laclos's Merteuil once again comes to mind, enigmatic and triumphant in her demiurgic projects despite the lame efforts of the plot to expose and discredit her, a plot that is obliged to give her smallpox and then claim that at last her soul shines forth on her face. Much could be said of Balzac's Vautrin as well, sphinx with an agenda of his own, at least insofar as he remains beyond narrative scrutiny in

Pere Goriot,

or of Dickens's inscrutable lawyer in

Great Expectations,

Jag-gers, who seems already to know all the dark secrets that Pip must suffer to learn.

Or of Faulkner's magnificent Addie Bundren who lies dying in his novel of that name, Addie who marked all who knew her, desired to whip her pupils so that they would feel her in their very blood, who yet retains a forbidding integrity, rotting in the coffin though she is, an integrity Faulkner calls pride: "that pride, that furious desire to hide that abject nakedness which we bring here with us, carry with us into operating rooms, carry stubbornly and furiously with us into the earth again" (1985,31). Note how Faulkner unerringly picks up on the medical side of this dilemma, sees the operating room as a rival force for exposure in this book where perception itself is imaged as a water hose that hits you full blast.

Or, consider, for true "good old boy" opacity, the testimony of Flan-nery O'Connor's mysterious Tom T. Shiftlet in her story "The Life You Save May Be Your Own":

"Lady," he said, and turned and gave her his full attention, "lemme tell you something. There's one of these doctors in Atlanta that's taken a knife and cut the human heart—the human heart," he repeated, leaning forward, "out of a man's chest and held it in his

hand," and he held his hand out, palm up, as if it were slightly weighted with the human heart, "and studied it like it was a day-old chicken, and lady," he said, allowing a long significant pause in which his head slid forward and his clay-colored eyes brightened, "he don't know no more about it than you or me." (147)

Country ignorance or country wisdom? One thing is clear: Shiftlet's bizarre actions in this story back up his assertion that human behavior often remains a mystery. O'Connor, more even than most writers, honors mystery, regards human motive as opaque; her characters apply the thin grids of reason to their lives (just as we do when we read her stories), but those lives are invariably fitful, animated by dark, imperious, and entirely unpredictable forces. In her work the revelatory and the traumatic are inseparable because grace or horror (or grace as horror) can pop out at any moment. So her stories make for tricky reading. We cannot, as it were,

possess

them.

As a concluding contemporary example, consider the appealing figure of Babette in Don DeLillo's comic novel

White Noise.

Babette, who is married to the narrator/protagonist and whose motivation becomes ever murkier as the text proceeds, comes fully into my argument when she forbids her husband to use words like "entering" to describe sexual congress; "We're not lobbies or elevators," she explains to him.

GETTING IN AT ALL COSTS

I would like to suggest that the narrative of exposure has this funny habit of treating its characters like lobbies and elevators, places to enter, moving places for you to ride in. It can hardly surprise us that medical narratives—whether in the form of fiction or in actual case studies— are full-fledged members of this family.

Consider William Carlos Williams's troubling story "The Use of Force" (troubling to scholars in literature and medicine, because the doctor/writer is stunningly open and unguarded in his account) in which

the emigrant girl stubbornly and passionately refuses to open herself to the doctor's ministrations. Attempting the time-honored medical entry of making us go "ahhhhh"—itself an act of forcible rescripting, of making the body speak to the scientist—this doctor runs into problems:

Come on now, hold her, I said.

Then I grasped the child's head with my left hand and tried to get the wooden tongue depressor between her teeth. She fought, with clenched teeth, desperately! But now I also had grown furious—at a child. I tried to hold myself down but I couldn't. I know how to expose a throat for inspection. And I did my best. When finally I got the wooden spatula behind the last teeth and just the point of it into the mouth cavity, she opened up for an instant but before I could see anything she came down again and gripping the wooden blade between her molars she reduced it to splinters before I could get it out again.

Aren't you ashamed, the mother yelled at her. Aren't you ashamed to act like that in front of the doctor?

Get me a smooth-handled spoon of some sort, I told the mother. We're going through with this. The child's mouth was already bleeding. Her tongue was cut and she was screaming in wild hysterical shrieks. Perhaps I should have desisted and come back in an hour or more. No doubt it would have been better. But I have seen at least two children lying dead in bed of neglect in such cases, and feeling that I must get a diagnosis now or never I went at it again. But the worst of it was that I too had got beyond reason. I could have torn the child apart in my own fury and enjoyed it. It was a pleasure to attack her. My face was burning with it.

The damned little brat must be protected against her own idiocy, one says to oneself at such times. Others must be protected against her. It is social necessity. And all these things are true. But a blind fury, a feeling of adult shame, bred of a longing for muscular release are the operatives. One goes on to the end.

In a final unreasoning assault I overpowered the child's neck and jaws. I forced the heavy silver spoon back of her teeth and down her throat till she gagged. And there it was—both tonsils covered with membrane. She had fought valiantly to keep me from knowing her secret. She had been hiding that sore throat for three days at least and lying to her parents in order to escape just such an outcome as this. (59-60)

The critics have had a few problems making Williams politically correct, and many of his doctor stories are quite disturbing in their callousness and unconcealed biases. But of course that is grist for my mill, because this passage pays explicit homage to the uncontrollable, almost ecstatic high that accompanies forcing open the patient. Williams's doctor forces open the girl's throat and finds her secret: tonsils covered with membrane (indicating diphtheria). James's governess corners the little boy, Miles, squeezes him mercilessly for his secret, and he dies. The outcomes are different, but the pride alluded to by Faulkner seems common to both.

Of course, we understand that verbal breaking and entering cannot be flatly equated with physical penetration. And yet everything I have said in this chapter—beginning with the parallel between my mother's exposure to the sun and the Proustian exposure to sexual activity, and continuing to the mystery of Chillingworth's impact on Dimmesdale— suggests that the human subject is invadable both physically and mentally, that the desire to "go in" takes both physical and mental shapes.

Feminists will say that this desire for penetration is a gendered affair (a male fixation), but we need to realize how such hunger constitutes the very pulse of fiction. Some might add, "the pulse of colonialism," as evidenced in the famous image of the ship in Conrad's

Heart of Darkness:

"In the empty immensity of earth, sky, and water, there she was, incomprehensible, firing into a continent" (41). In today's academy, Conrad is now seen along increasingly ideological lines, and citations such as the above offer evidence for the European hunger to colonize and control

the non-Western. But the sheer ferocity of the image—"firing into a continent"—also conveys for me an extraordinary appetite of a different sort altogether, a diagnostic and readerly "tracking" that Conrad's famous narrative technique (Marlow "reading" Kurtz) displays to perfection. Marlow's pursuit of Kurtz into the dark continent keeps covenant with the earlier diagnostic projects of Richardson and Diderot, even if Conrad has created a conjectural mode of fiction that accommodates ignorance, guesswork, and outright personal fantasy.

Not that the personal and the ideological are at odds with each other. We have seen that Charlotte Perkins Gilman's version of a male doctor "reading" and "tracking" his sick wife plays entirely into a cultural nexus that infantilizes women and regards any resistance as hysteria. Conrad's Kurtz ultimately resists any definitive reading that Marlow can foist on him; his motives stay shrouded in darkness. But the story of the "target," the human subject slated for "study" and "knowledge," is indeed one that can and must be told.

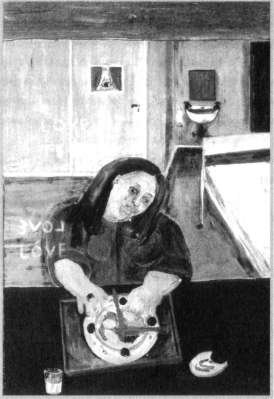

How does it feel to be on the receiving end of the diagnostic attack? The Swedish artist Lena Cronqvist has left us some remarkable paintings testifying to her stint as caged object of study when she was confined in the mental hospital, St. Jorgens, in the wake of a depression.

Locked Up

(see next page) provides a poignant image of the patient's disarray. All is twisted and tilted in this picture: the subject's dazed eyes and wrenched face, the knife and fork ajar on the plate, the skewed perspective of the entire piece with its sense of both falling and weightlessness, as if the tray were vertical rather than horizontal, the eating surface falling away, the glass insolently perched, the partly eaten sandwich (which looks like a carving) flaunting its reified status—all compounded by the groping fingers that fumble at the (strange, inedible) food. Everything is made alien here, and the inscription of "LOVE" written both forward and backward, as if to signal the awful dislocation and reversal at work here, tells it to us in yet another key. As every spectator immediately notes, the crowning touch of this depiction of consciousness at once amok and under surveillance is the obscene eye in the door, an eye