As Easy as Falling Off the Face of the Earth (3 page)

Read As Easy as Falling Off the Face of the Earth Online

Authors: Lynne Rae Perkins

The train slowed further as it pulled past—humans! Sitting in lawn chairs, next to a little house. Concrete grain elevators. A scrapyard full of heaps of curled metal rubbish. And the trainyard. Suddenly there were several tracks, and other trains, and pieces of trains, unidentified industrial objects, buildings. And people working.

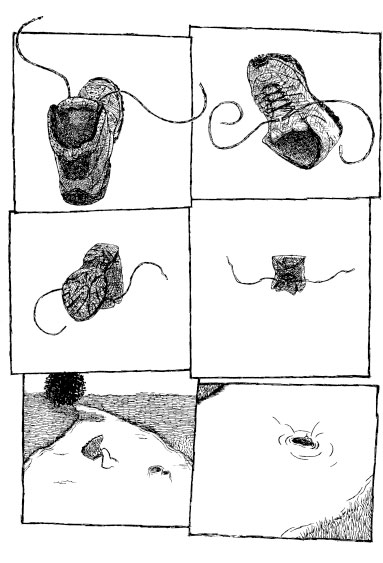

Ry decided to jump off before they saw him sitting there. The train was barely moving. He jumped without incident and limped (on account of the missing boot) hurriedly over behind some rusting piles of industrial detritus. Not seeing an inch-thick rusted steel cable because it was in shadow and coming straight at him, he walked into it. It hit him just above his right eye. He jumped back and let out a yelp and his hand flew up

to where the pain was. He clenched his eye shut and hopped up and down in a circle.

Then he stood still. He moved his hand up just slightly and opened his eye.

“I can still see,” he said. “That’s good.” He took his hand away and looked at it.

“No blood,” he said. “That’s lucky.”

He couldn’t help smiling a little despite the searing pain, because this made him think of the joke about the blind dog with three legs, no tail, and major bald patches.

“What’s his name?” someone asks.

“Lucky,” says the dog’s owner.

He stood there on the rusted, frayed edge of some town in Montana at sunset. He could feel warmth around his eye as the swelling narrowed his eye opening to a slit. But it didn’t swell shut completely. That was lucky.

“I’m so lucky,” he said to himself. “Lucky, lucky, lucky.”

Ry had been happy to see the town on the horizon, but now that he was here, what was he supposed to do? Where should he go? Who should he talk to? He pulled out his phone again and turned it on. There were five messages:

Jake was bored—how was the train? Amanda just saw that one guy at the mall. Again. From Eric:

Dude, you at camp yet?

From Nina:

Hey, have you talked to Amanda? She won’t talk to me.

From Connor:

Wanna play b-ball?

“I don’t live there anymore, remember?” muttered Ry.

He sent out a mass text:

Where am I??!!!??

No Grandpa, no parents yet. He called them both.

“Call me,” he said. “I have to turn my phone off, but leave a message.”

Food, he thought then. I have to eat.

He did have some money in his wallet.

Past another phalanx of grain elevators, he found himself in front of a sign with two arrows at the lower end of a bridge that went over the train tracks. The arrow pointing left was next to the words

Business District

. The arrow pointing to the right was next to the word

Canada

.

Ry headed for the business district. It was the old downtown. About half of it was boarded up. Of the other half, what was still open at this time of day was bars. He decided to try the next block over. The movie theater was open. He could even afford it, but it might not be the smartest move. When he came out, it would be night, full on.

He soon walked into a welcoming neighborhood of tidy houses with trees and bushes and vacu-formed and extruded plastic toys in cheerful, noxious colors sprinkled across the yards. Ry felt he was walking into a club of which he was a member, and he walked down the sidewalk with some confidence that no one glimpsing him through a front window, with the distance of a front yard separating them, would take any notice of him. (He was forgetting a few aspects of his current appearance.)

It was not the kind of club where he could walk up and knock on someone’s front door, though. Not like in the very olden days when travelers were taken in (and fed) by total strangers.

He had never before studied a street in terms of the places it provided for shelter. The pickings were slim. Maybe after everyone went to bed, he could sit on someone’s porch. He walked up one street and down another, the streets filled with houses. The houses were filled with people who had lives and families and friends, but he had no connection to any of them.

The houses had windows that were beginning to glow, golden with lamplight or blue with TV light, as dusk sifted down. Whiffs of dinners, wafts of conversation murmured through the air—good smells, friendly sounds, but he

had to keep walking as if he had somewhere to go.

How good it would feel if one of the houses would take him in. If a door opened and a familiar voice called out, “Ry! Get in here! Where have you been?”

He decided to go back to the street with the bars. At least he could get a burger or something. But he had turned a few corners and, trying to retrace his steps, he must have missed a turn. Because here was a park, with a gazebo. He was pretty sure he hadn’t passed that before. Or this school. Or this church, with its yellow bricks illuminated by lights hidden in the shrubbery.

Other than the gazebo park and the school and the church, the rows of houses and trees might as well have been twenty-foot-high hedges in a maze. Ry was the rat, searching for his cheese. Burger. The tired, hungry rat.

All of the people seemed to have gone inside. For dinner, no doubt. Chicken, maybe, or spaghetti. Up ahead, though, a guy was in his driveway, doing something with a truck and a welding torch. In the fading light, it was hard to make out what he was doing, exactly, but it looked like he had chopped apart a couple of pickup trucks and was welding them together in a new way. The cab of one pickup truck now rested somehow on top of the walls of the box of another pickup. Both pickups

had the rounded shape and the aura of automotive ancientness. The guy who was welding had his back toward Ry. As Ry approached in his weakened, famished state, he fell under the spell of the welding torch and he stopped, transfixed by the flame and the sparks flying into the onset of a night that had no place for him. He thought he might watch, just for a minute or two, and he sat down, almost without realizing it, on a small stack of tires that some lobe of his desperate mind had noticed.

Once he sat down, it seemed unlikely that he would be standing up anytime soon. The streetlights flickered on, and one of them lit Ry up like a lone actor on a stage. But still, he didn’t move. He couldn’t move.

The welder took his mask off, then. He noticed Ry, and nodded. He worked for a few minutes longer, putting his tools in order. He saw that Ry was still sitting there, and said, “How’s it going?”

Ry opened his mouth for the word

okay

to come out. Instead, his lips lost their ability to form that word, or any word. A sound issued from his throat, but it left his mouth unshaped. Tears were forming and welling up in his eyes. He clenched his jaw and fixed his gaze on the odd-looking truck in an effort to stop the tears from spilling out onto his cheeks. He focused on the truck.

The two trucks. Seeing, without seeing, the door handles, the bumper, the dull red spots of primer, a sticker on a window.

“What’re you doing?” he croaked finally. He was embarrassed by his voice, but relieved that he had managed to speak. He cleared his throat and said, “I mean, it looks cool, but can you actually drive it, on regular roads?”

By the end of the sentence, his voice sounded almost normal. Normal was what he was going for. Forgetting, just briefly, how not ordinary it was to materialize in a total stranger’s driveway at nightfall, filthy and bruised and on the verge of tears, in a torn bloody T-shirt, wearing only one shoe.

Del had taken note of all this while Ry was gazing fixedly at the truck. He guessed at Ry’s age—fourteen? Fifteen? And wondered who had roughed him up. He wondered if the boy would tell him. “How’s it going?” had apparently been way too intrusive. Maybe he was hungry. Maybe the best thing would be to feed him.

“I was just about to go get a bite to eat,” he said. “Have you eaten?”

“You mean, like, today?” asked Ry.

“I mean, like, recently,” said Del.

“No,” said Ry. “I had breakfast.”

“Okay,” said Del. “Wait a minute.” He opened one of the truck doors, leaned inside, and emerged with a clean, folded T-shirt and a pair of flip-flops.

“Here,” he said. “Put these on. We’re not going anyplace fancy, but your shirt’s looking a little unappetizing, and you need to have shoes on both feet. My name is Del.”

“I’m Ry,” said Ry.

“Do you want to go inside and wash up first?” asked Del. “The bathroom is straight ahead.”

Ry had never before been so happy about soap and warm water, and then a towel. He felt like singing. But didn’t. He examined his reflection in the mirror. It was true that his T-shirt was now a shredded dirty rag. Looking down, he remembered that it was bloodstained, too, from his nose. He pulled it off and put on the fresh one, which was tan and had a picture of a tree on it.

He checked himself out in the mirror again, this time admiring his blossoming black eye. His eyeball blinked back at him through a crevice in the swollen discolored hillock that was now the most striking feature of his sunburned face. Kind of cool looking except that it hurt. A dull ache with a throb.

It occurred to him that the mirror was the door of a

medicine cabinet. On the premise that medicine cabinets were like bathrooms in fast food restaurants—a shared resource for the common good—he opened the door. There was a razor and a shaving brush. Toothpaste and toothbrush. Earwax removal fluid. A jar of Vaseline. A bottle of generic aspirin that had two tablets left.

Ry hesitated. He put the bottle back on the shelf and closed the door.

The velvet black sky was crammed thick now with stars. And the air was chilly, especially on sunburned flesh. Ry shivered, and put his hands as deep in his pockets as they would go. His bare toes and heels hung over the edges of the flip-flops. They looked like girl flip-flops. Kind of skinny, and they were turquoise. Del came out of the garage, pulled the door down, and nodded toward the truck.

“Hop in,” he said. “Let’s see if we can drive it on a regular road.”

Climbing up into the old truck was like stepping into a time machine. The worn leathery seat and the spacious darkness of the cab, with lighted dials glowing from the dashboard, lighting the rounded edges of knobs and levers, gave off an immense feeling of safety. Ry wanted to stay there forever, except that he was starving. His stomach was

now making the cartoon sound effects for two space aliens having a fistfight. Or whatever kind of fight they had.

“What are you doing to this truck?” he asked again. “I mean, why are you putting the other truck on top of it?”

“Everyone wants to ride in the front seat,” said Del. “Everyone wants to look out the front window.”

“How will people get up there?” asked Ry.

“I haven’t quite figured that out,” said Del. “But I’m working on it. I have some ideas.”

“Do you have a big family?” asked Ry. Because he was wondering who “everyone” was, who needed to have seats in the front.

Del considered the question before answering.

“Not strictly speaking,” he said. “Do you?”

“No,” said Ry. “Just my mom and dad. And our dogs. And my grandpa.” Mentioning them was like looking down from the tightrope, remembering the precariousness of his situation, losing his balance. Looking up, he saw that they were pulling into a small gravel parking lot alongside a boxy gray building.

“Do they know where you are?” ventured Del as they got out of the truck. The doors ka-thunked shut, they walked the short distance to the restaurant.

“I don’t even know where I am,” said Ry.

The restaurant had a theme of mining. There was a framed brownish photograph of old-time guys with suspenders and brimmed hats standing at the opening to a mine, right inside the door, and a pickax and shovel hanging from the wall behind the counter. Aside from that, the theme of the place was brown. Even if your eyes were closed, the tiny molecules of gravy and meat, the golden brown molecules of the crust of rolls and of French fries, suspended in the air as thick aroma, would tell you that.

Eyes open, there was brown paneling on the wall, wood-grain Formica tabletops, an all-over brownness. With white lighting: bare fluorescent tubes over the counter and fake oil lanterns on the tables. It was nice. Not like his own home, but homey somehow.