As Easy as Falling Off the Face of the Earth (8 page)

Read As Easy as Falling Off the Face of the Earth Online

Authors: Lynne Rae Perkins

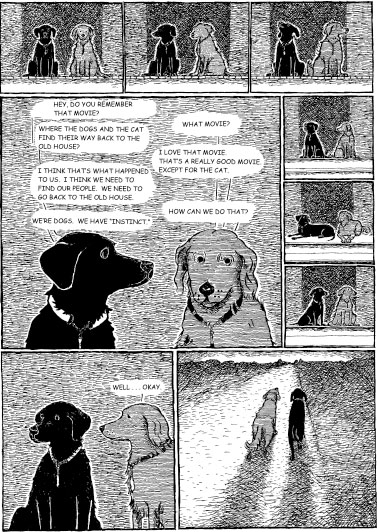

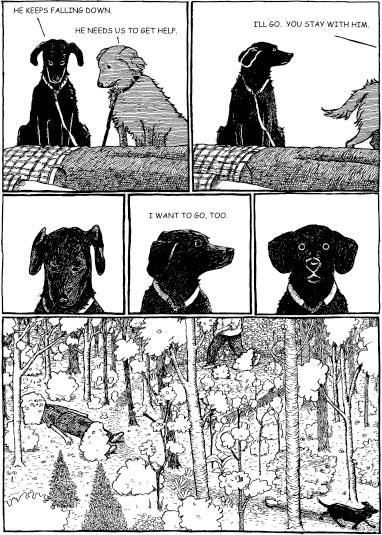

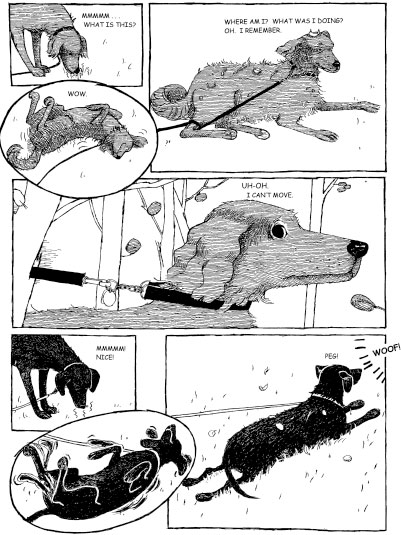

DOG VERSION

R

oughly thirty-four hundred miles to the southeast of New Pêche, the sun was setting. Ry’s mother and father dangled their feet from a dock attached to an island and watched it. Once it got close to the horizon, it fell so quickly. The sky was deep blue, lavender, peach, yellow, tangerine. Just ahead of them, the shore curved around and offered up picturesque palm trees in silhouette. Gray violet cloud wisps drifted along in the distance.

“What an absolutely beautiful sunset,” said Wanda.

“We should have done this years ago,” said Skip.

“You’re right,” she said. “I just always worry—”

“You don’t need to worry,” he said. “Everything will be fine.”

“I liked his old camp where they made them write postcards home before they could eat dinner,” she said.

“Where would he send them?” asked Skip.

“I don’t know,” she said.

“Don’t worry,” he said. “Everything is fine. Nothing’s going to happen.”

T

he crew caravanned to Del’s house to unload the hunks of chopped-up tree into stacks in his backyard. Ry fully intended to help out with all that, but he slipped into the house, for only one minute, to plug in his phone. In the kitchen he busted open the packaging of his new charger and scanned for an outlet. The voices of the others shuttled past the open window. Weren’t there any outlets in this house? Was Del waiting to see if electricity was a fad, too?

Aha! He found one. The phone lit up. He turned to go back outside, but the phone called him back. It said there were messages. He would just check.

From Nina:

You’re in Montana. Right?

From Connor:

I don’t know. So, you wanna play b-ball? Oh, wait—you moved. Duh.

Ry gave his phone raspberries. He didn’t text back. And when no one answered—grandpa, mother, father—he didn’t leave a message. He stood in the dim kitchen, thinking. He had relatives, aunts and uncles. They were far away, and he didn’t have their numbers with him, but they existed. He guessed that was the next thing he should do. He was starting to work it out when he heard Del’s voice outside the window.

“I’ve been thinking about it,” Del said. “I think I should just give him a ride home.”

“What?” said Beth.

Ry drew closer. Beth was tossing Del chunks of wood from the bed of Pete’s pickup. Del was stacking them next to the house. Their conversation was punctuated by wood falling on wood.

“I could loan him the money for a train ticket,” said Del. “But it just doesn’t feel right to put him on a train when we don’t know for sure that someone’s going to be there at the other end. I would feel responsible if something happened.”

“That must be why you had him shinny out on a dead tree limb,” said Beth.

“He was wearing a harness,” said Del. “It was completely safe.”

Ka-thunk.

“I guess,” said Beth.

“And besides, it’s fun,” said Del.

“Uh-huh,” said Beth. “He looked like he was having a great time.

“Doesn’t he live, like, a thousand miles from here?” she asked. “That’s a bit of a hike.”

“I was thinking of heading in that direction anyhow,” said Del. “I have some errands to run out there.”

Thunk

.

“Right,” said Beth. “Errands. In Wisconsin.”

Clunk. Chunk.

“On the way there,” said Del. “More likely on the way back. People I haven’t seen for a while. It’ll only take a couple of days. Three or four, round trip.”

Ry stepped quietly backward into the shadowy house. He went out the backdoor, to where Pete and Arvin were ka-thunking their own pile of wood alongside the garage. He helped them stack, but his thoughts blurred out their conversation. They spoke to him a few times, and laughed when he didn’t answer.

“He’s somewhere else right now,” said Arvin. Pete moved his hand in front of Ry’s face. “Come back,” he said. “Anybody there?”

Ry came back into focus. “Oh,” he said. “Sorry. I was thinking about something.”

“What’s on your mind?” asked Arvin. “Hey…you all right?”

Ry needed to talk it around. So he told them about the conversation he overheard between Del and Beth.

“In a way,” he said, “It would be easier for me than anything else. Otherwise, it’s finding my relatives and them buying me plane tickets and flying me wherever when probably my grandpa just isn’t answering the phone. I hope. But what kind of person does that? Isn’t it kind of…extreme?”

Arvin answered first. “Only compared to most people,” he said. “But that’s not saying much. Delwyn is a man who likes to—how should I say it—he likes to rise to the occasion.

“Like driving you home all the way to Wisconsin. Nothing could make him happier. Unless maybe it’s picking up three hitchhikers, getting a cat down out of a burning building, and rebuilding someone’s transmission with nothing but a fingernail clipper along the way. Mainly I think he just wants to make sure everything’s okay.”

Del called to Arvin to give him a hand, and Arvin started to head over. Then, turning and smiling his big smile, he said, “Oh, yeah. Watch out for damsels in distress, or you might never get home.”

Pete had something he wanted to say, too.

“It’s true that Del is an unusual person,” he said. “He has his own rules. You know how Thoreau talks about the guy who marches to the beat of a different drum? Well, Del marches to the beat of, like, I don’t know, a harmonica or something.

“What I’m saying is, sometimes it might seem like he’s out of his mind. Maybe he is, in a way. I mean, who isn’t, right? But don’t worry. You’ll be okay.”

Then he said, “Hey, I better go help those guys.” And off he went.

But Beth materialized beside Ry like the third visitation, the Ghost of Christmas Future.

“Do you think Del is nuts?” Ry asked her.

“Who said that?” asked Beth.

“Pete,” said Ry.

Beth snorted. “I guess he should know, right?”

“Not exactly,” said Ry. “He said that Del marches to the beat of a harmonica.”

Beth tilted her head back and let out a “Ha!”

“Okay,” she said. “That I’ll buy. That’s actually pretty good.”

Ry told her how he had heard Del’s idea through the kitchen window. And how he didn’t know what to think about it.

“Are you worried?” she asked. “Because you don’t need to be.” She seemed about to go on, to say something more, when Del approached and said, “Worried? What are you worried about?”

Flustered, Ry said, “I’m worried about my grandpa. How he’s not answering the phone.”

“Let’s go find out what’s going on,” said Del.

“I already told him about your idea,” said Beth. Just to keep things simple.

“What if something happened to him?” said Ry. “What if—?”

“Then we would have to go find your parents,” said Del.

Ry looked at him. Trying to tell if Del was serious. He couldn’t tell.

“I don’t even know exactly where they are,” he said. “There are, like, a thousand islands down there. And I don’t have any money. It would be impossible.”

“Uh-oh,” said Beth. “Those are magic words to Del. But I don’t think even you can drive to a Caribbean island, Del.”

“We’d have to get to San Juan,” said Del. “Then we’d have to borrow a boat.”

“San Juan,” said Beth. “Hmm…isn’t that where Yulia lives?”

“It’s just a hypothetical situation,” said Del. “It’s pretty unlikely that it would ever actually come up.”

Maybe that piece of the conversation made driving to Wisconsin seem completely reasonable. Because then the talk went from whether they should go, to which vehicle they should take. Not the double-decker; there were only two of them. Del decided on a Willys. He had two. They were really old Jeep station wagons. He had modified them in a number of ways, one being that he made them longer in the back, so that two sleeping bags could fit there, stretched out full length. And he decided that, if they were going, they might as well get started. Before Ry knew it, Del had thrown the sleeping bags in and they were saying good-bye.

Beth took Ry’s head between her hands and kissed him on each cheek. She was that kind of person. She also gave him a little peck on his bruised eyebrow.

“Makes you look like a tough customer,” she said. Then she took his right hand in both of hers and shook it.

“Don’t worry,” she said, still holding on. “I’m betting everyone is fine. I bet it’s just a bunch of mix-ups.”

“Watch out for those damsels,” said Arvin. “If you see one, make sure Del is looking the other way.”

“What damsels?” asked Del.

“Just joking,” said Arvin. He winked at Ry.

“Well, I guess we better go then,” said Del.

And then they were going, backing out of the driveway, waving good-bye, rolling down the street. Houses, streets, minutes, and miles came and went, all ordinary enough. Ry could not identify the odd sensation he had as they rolled along. Maybe it was what a lobster feels when it finds itself in a pot of water that started out cold enough but seems to be starting to boil. Or what a snake feels as it warms on a rock, having shed the skin it has outgrown. Or maybe it was just the truck’s heater in the cool of the evening. But it seemed to signal the beginning of something, a change. A sea change. Or, in this landlocked place, a shifting of the ground beneath.

Lights were appearing: headlights, dashboard lights, lights in houses. It was the hour when lights start to matter. They were exiting New Pêche almost exactly twenty-four hours after Ry had entered it. One day.

Back out into the uninhabited veldt they went. From the inside of the Willys, though, with a half-eaten Skilletburger wrapped in paper in one hand and the other half working its charms within him, the friendly thrum of the engine, another human being nearby, even scratchy music fighting its way through the airwaves

and out of the old radio, the darkling world outside them seemed large and lonely in a more homey, though still mysterious way. The oncoming night blurred and swallowed up most of the vastness, leaving Ry and Del a more manageable, headlight-sized portion to deal with. Two lit cones merging into one, gray road, white and yellow traces of paint, the shoulder of gravel, dirt, and weeds. Occasionally the headlights of an oncoming car or truck appeared in the distance, grew closer, then swept by with a Doppler-ating groan.

When the burger and the cola were long gone, the darkness around the headlights was all enveloping, and focusing on the lit patch of asphalt always moving under them was like watching a scene in a movie where nothing happens, where nothing ever will happen. As if the camera was left on accidentally, pointed at nothing, and you wait for the scene to change. It was then that a picture formed itself in Ry’s mind. The clutter on Del’s countertop. Including his phone, plugged into the kitchen wall. Four hours behind them. He reached into his pocket.

Crap.

Is it any different to have a phone when no one you call answers, than not to have a phone at all? It did seem

different. If you had the phone, there was the possibility that someone would answer, eventually. The night outside seemed blacker without it. Bleaker.

But at least they were on their way to his house.

The engine balked and stuttered, then stopped. They rolled for a short distance in silence before Del guided the truck off the road, where it came to a standstill, in the middle of the night, in the middle of nowhere.

“Damn,” he said.

But he sounded happy.