As Easy as Falling Off the Face of the Earth (12 page)

Read As Easy as Falling Off the Face of the Earth Online

Authors: Lynne Rae Perkins

F

inding Ry’s house wasn’t hard once they made their way from the scraggly it-could-be-anywhere zone to the old downtown. Ry knew his way from there. He had walked it a few times; a few lefts and a right and there it was.

His grandpa’s car was parked in the driveway. Warm relief flowed through Ry. Quick on its heels came a colder, clammier wave of apprehension. He tried to shrug it off, but he couldn’t, not quite.

The front door was locked, and so was the back. That was weird. Ry tried both doors, then rapped on them. He peered through the windows, but he couldn’t see anything. Or hear anything. No footsteps, no TV, no barking dogs.

Then he noticed that the back door to the garage was

open. Not only unlocked, but open. Ajar. Just an inch or two. He stepped inside and paused for an instant while his eyes adjusted. There was the food and the water bowls for the dogs, alongside a giant open bag of dry chow.

Ry reached for the doorknob on the door that led from the garage into the kitchen. This one was unlocked. Lucky. He stepped up into the house. Del came in behind him. They both felt the insides of their noses curl up and shrivel somewhat.

The smell turned out to be coming from the coffee pot. The little orange light was on. Ry flicked off the switch and lifted the glass carafe from the warming plate. A thick, tarry substance in the final stages of coffee death was enameled to the bottom. The aroma was no longer of anything you would want to put inside your body. Ry turned and showed Del the pot.

“It was still on,” he said. “You want some?”

“No, thanks,” said Del. “I think I’ll pass.”

He came over and looked at it, though. It was only nine o’clock in the morning. They both knew that it took more than a few hours to cook a slab of solid coffee like that. It wasn’t from today. Maybe not even yesterday.

“Let’s just take a look through the house,” Del said, “and make sure everything’s okay.”

So Ry led Del up the stairs and into the hall. When they reached a doorway, he stepped back and held out his hand as if in courtesy, “After you.” If everything was not okay, he didn’t want to find out first.

His parents’ room was disheveled, but they had disheveled it themselves, packing for their trip before they finished unpacking from the move. The covers had been pulled up on the bed, and a lone photograph had made it up onto the wall. The rest of it was a free-form jumble. Ry saw the layers of clothing draped over the back of his mother’s chair and knew that she had changed her clothes at least three times, just to go to the airport.

Ry’s room was just as he had left it, too. He didn’t know anyone in this town yet, so there had been plenty of time to set his room up the way he wanted it. The decorating style he preferred was somewhere between Extreme Lived-in and Total Pit.

Lair

was how he thought of it. So at first glance it was as chaotic as his parents’ room. Maybe more so. He had a lot more stuff on the walls than they did, and more things plugged in. He would have liked to just stay in there for a while and soak up the ambience, but Del moved on, and Ry made himself follow.

They went into the small spare bedroom where his

grandfather had set up camp. This room was orderly. The bed was made. An open book waited facedown on top of the clock radio on the nightstand. Several shirts hung in the open closet, along with a pair of blue jeans and a pair of khaki trousers, neatly folded in half on the hangers. A pair of moccasins had been dropped onto the floor.

The bathroom was tidy and clean. Almost too tidy and clean. It was as sparkly and shiny as a bathroom in a hotel.

“I wonder where his toothbrush is,” said Del, “and his razor.”

They went back into the bedroom and looked around, opened the drawers in the dresser. They saw socks and underwear, but no toothbrush, no razor or anything like that.

“That’s kind of weird,” said Ry. “His car is here.”

They went back downstairs and Ry led the way to the basement. Then up again and out onto the back porch. They went out into the yard and walked around. They looked inside the garage. Nothing seemed odd or amiss, except that no one was there. No dead bodies, but also no grandpas. No dogs. Not sure what else to do, they headed back inside.

A small hill of mail had fallen to the floor from the

slot in the front door. A couple of days’ worth, maybe. Ry gathered it up and riffled through coupon flyers addressed to Occupant, a magazine, and some envelopes with the yellow forwarding stickers, something from the electric company. He set it all on the coffee table and sank into his dad’s favorite chair. He closed his eyes. He considered keeping them closed until everything had turned out okay. Then he opened them and looked around at the familiar furniture of his life that had moved into this house and taken up residence. He was glad to see it all—the lamps, the knickknacks, the throw pillows. The steadfast couch welcomed him like a childhood friend.

It seemed for a time as if he might sit in the chair all day, or forever. But then, in a surprise move, his limbs assembled themselves and propelled him to the answering machine, on the desk in the alcove off the front hallway. It was blinking. The number of messages it wanted to deliver was ten. Ry found a piece of paper and a pen, and pushed the button.

T

he first three messages were his own. Maybe the fourth, too; it was a hang-up call.

The next one was from Ry’s parents. His mother said that they had climbed a volcano, a mostly but not completely dead one.

Dormant

, that was the word. It had jungles growing all over it. And monkeys. Greenish monkeys. She wasn’t sure if that was their natural fur color or if they were moldy. She had called to tell Lloyd that they were having a really nice time, but they had lost their cell phone somewhere along the way. If he needed to reach them, he should just check the itinerary for where they were going to be and leave a message there.

The message after that was from a doctor’s office. A woman’s voice said that she was following up on Mr. Farley’s visit to the emergency room.

Would he please call this number and let her know how he was doing?

Ry scribbled down the number.

The emergency room? His grandpa?

The machine beeped, the number changed from five to four, and his mother’s voice was talking again. As if to someone next to her, she said, “It is the right number; it has Ry’s voice on it.”

And, into the phone again, “Dad, we just wanted to let you know we’re not where we’re supposed to be right now. In case you tried to call us there. We are—(aside again) where are we? Saint who? (and back into the phone) We are on Saint Anomie. Anomalie. Amalie. Ennui. Henri. Something like that. It’s a French name, it starts with an ‘ah.’ Annalee, maybe. They speak with a strong accent. It’s beautiful, but I have trouble making out some things. And I hate to keep asking.

“Anyway. We had an eventful day today. We got blown off course. We were in some fairly strong winds, but we were doing all right until the mast snapped in half. Like

a toothpick. The main one, with the biggest sail. I won’t go into all the details, I didn’t even know what was going on half the time, but let me tell you, I was glad to get to this little island, whatever it’s called.

“So, let me give you the number here.” There was some fumbling and some muffled conversation, then his mother repeated a phone number someone was giving her. “We’ll stay here tonight and then try to find another boat tomorrow. With a better mast. But everything’s fine; all’s well that ends well. Skip twisted his ankle when he jumped off the boat, but we have it wrapped up really nicely in an Ace bandage and he can walk on it. Sort of.

“And now we’re going to go find some beverages with umbrellas in them. At least, that’s what I want. Bye for now.”

Click. Beep.

Number eight was a hang-up call.

Now Ry heard his grandfather’s voice.

“Listen,” his grandfather said. “This is Lloyd. I hate to bother you, I really do. I’m sure you have a lot going on. The thing is—I don’t know where the hell I am. I

thought you might be able to tell me. Did I have any travel plans that you know of?”

There was a pause. A long pause. Then his grandfather said, “Oh, no!” Softly, as if taken by surprise. There was a crashing sound, followed by a harsh groan, as if of pain. And then a click.

A beep. Ry’s dad spoke this time.

“Lloyd? Are you there? Are you okay? We’re concerned that you’re not answering the phone. I suppose we’re just missing you, or maybe you don’t have your hearing aid turned on. We’ll keep trying.

“Anyway, listen, we’ve had another little glitch. We got the new boat, and we sailed today to a little island called Saint Jude’s. All that is fine. But we went swimming at this beautiful beach that we thought was totally deserted. Only apparently it wasn’t, because while we were in the water, everything we left on the beach disappeared. Passports, credit cards, even our beach towels.

“Fortunately, we have clothes on the boat and some cash that we tucked away. But we will be here for a few days, anyway, waiting for our stuff. Tomorrow is some kind of a holiday, and I guess nobody does anything over the weekend, unless maybe your life is in danger.

“By Monday we should have everything we need. I’m not sure where we’ll go then; we’re a little up in the air about that. We’re just going to bunk on the boat; we don’t have a number where you can reach us right now. We’ll call again as soon as we know more.

“Okay. I guess that’s it. Bye for now. Answer the phone next time, okay?”

The familiar voices floated in the air, then they were gone. The machine announced the End of Messages. Ry had pulled the chair out to sit down at the desk while the messages played and, for a moment, he sat there without moving. He wanted to hear the voices again, but he wanted them to say different things. Or to be coming out of the actual people, who would be standing there beside him.

I

t wasn’t like a soap opera, where the person has amnesia and doesn’t remember who he is. Lloyd knew exactly who he was. The part of his brain that had been bruised and jumbled was the part where more recent information was processed. The waiting room of his brain, the lobby, where information paced back and forth while it waited to find out what room it would be housed in. Sometimes the information went around a corner, and he couldn’t locate it. Then it would appear again. Sometimes the information just disappeared and never came back.

This made it hard to watch television. He could watch game shows, where they asked for trivia from the past. But the programs that required you to keep track of what had happened just before the commercials? No. Mostly not. His hand went to a bump on his head. It felt tender.

He did not know how he had come to be in this hotel room.

Looking for clues in his wallet, Lloyd found a piece of index card cut down to fit inside one of the slots. Three phone numbers were written there, in his own handwriting, next to the names of his daughter, her husband, and his grandson. He had noted that two of the numbers were cell phone numbers.

There was a telephone in the room. Lloyd called all three numbers. No one answered. “Leave a message,” they all said. Well, what good would that do? What if he wasn’t here anymore when they called back? He decided to leave a message anyway, at the number that wasn’t a cell phone. As he spoke, he pushed open the drapes and looked out the window. For Pete’s sake, he thought. I’m a reasonably intelligent person. I know my address and I have credit cards; I’m sure I can get home. Then he would go see his doctor and figure it out.

He had the feeling he had already been to a doctor, but it was a blurry feeling. There was a blind spot in his thinking that kept moving around. But he thought he could work around it. He would just write things down as he figured them out. A notepad and a pen sat on the desk by the phone, and Lloyd picked them up.

He still held the phone to his ear, but he stopped speaking as he studied the scene outside. The license plates were a different color. What state was he in? Down on the quiet morning sidewalks, a movement caught his eye.

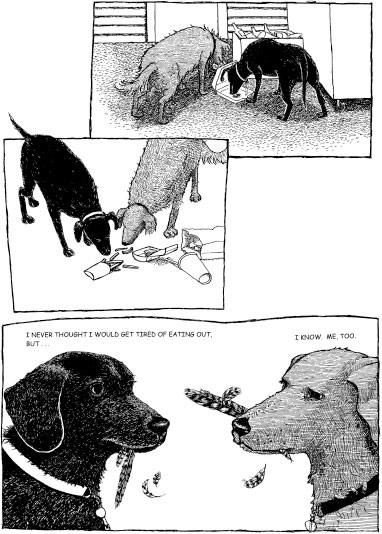

Two dogs, a reddish one and a black one, nosed along. They weren’t accompanied by a human, which seemed odd on a city street. The black one rose up on its hind legs, rested its front paws on the lip of an overflowing trash can, and retrieved a wad of paper. Something fell from the paper when the dog shook its head, and both dogs snarfed it up.

Two dogs. A reddish and a black one.

“Oh, no!” he said softly. He was supposed to—

The two dogs trotted into an alley in the middle of the block and out of sight. Lloyd spun around so quickly that he went off balance, which didn’t help the workings of his brain any. It was injured and susceptible, in the way that when you bite your tongue once, it seems to swell and then you chomp on the same spot over and over. Flailing to steady himself, he dropped the phone and knocked into the lamp with his elbow, his funny bone. The lamp crashed to the floor, and Lloyd let out a load groan of frustration and funny bone pain.

He replaced the receiver and righted the lamp. He

scrawled “dogs!” on the notepad and slipped it into his pocket, along with the pen. Then he hurried from the room, found the staircase, descended three floors worth of worn blue-carpeted steps and exited the building.

His eyes fell on the trash can and the fast food wrappers. A light summer breeze sent the crumpled paper skittering into the alley where the two dogs had disappeared, and Lloyd followed, too. The dogs weren’t there anymore, but maybe he would be able to see them from the other end.

That street was a big street, and busy. Cars and trucks fumed in both directions, inching along, then shooting forward without mercy. There weren’t a lot of people on the sidewalks, but the ones who were there meant business. The air was full of diesel exhaust, the sound of truck brakes, and the not-too-distant

peep-peep-peep

of something backing up. A motorcycle revved its engine. Pigeons stepped by, unconcerned. Their iridescent feathers were magnificent in the sunlight that fell straight down between the buildings. It was an east-west street.

Lloyd pulled the notepad from his pocket—“dogs.” Right. He was looking for the dogs. He looked to his left, but saw no dogs. To his right, no dogs. He took out the

pen and added, “Peg red, Olie black.” That had popped into his head.

Across the street was a square green park. A vendor was setting up his hot dogs, buns, and condiments on a silvery cart. Beyond that, the park had a pond, with ducks. And there, watching the ducks, were the two dogs. Lloyd hurried to the corner and pushed the Walk button. His view of the pond was now blocked by bushes. When the light changed, he walked briskly across the street and into the park. Once there he saw the dogs leaving through an opening in the bushes on the far side.

“Peg!” he shouted. “Olie!” The dogs continued on their way. They made a right turn and then vanished. Lloyd hastened through the park in hot pursuit. The two dogs, who were not Peg and Olie, found their way to their own doorstep. By the time Lloyd walked past the tall narrow house in a row of many such houses, the dogs were having kibble and water in their kitchen.

Lloyd walked up and down the strange streets, looking for them. He could not recall how he had misplaced them in the first place. He was not familiar with this town. A map might help. If he could remember where he was supposed to go.

He felt he was on the verge of remembering all of it.

He came upon a restaurant with tables set up outside on a patio and decided to sit down there and think. He ordered coffee and a pastry. The license plates on the cars, he observed, were mostly Illinois plates. What the hell am I doing in Illinois? Lloyd wondered. The face of a woman flashed through his mind. He had met a beautiful woman. She had helped him in some way. When the waitress left the check, he reached for his wallet, only to find that it wasn’t there. He stood up and checked all of his pockets. Twice. He had the notepad and the pen, and some loose change. No wallet. No cash. No credit cards. No phone numbers.

Lloyd smiled at the waitress as she refilled his cup and thanked her. Then he did something completely un-Lloydlike. He left his pocket change on the table—it wasn’t enough, but it was all he had—and walked out on his check. He didn’t look back. Feeling like a criminal, a fugitive, or at least a creep, he turned a corner at the first opportunity.

As Lloyd walked along, a car pulled up alongside him and kept pace with him. He was afraid to look at it directly, but he could see it from the corner of his eye. This was a seedier part of town, no sidewalk cafes or parks with ponds here. No houses, even. He glanced to

his right into a derelict storefront. The display windows offered party supplies from some previous decade, one he hadn’t paid attention to. The dirty windows reflected the image of the car behind him and he tried to see who might be inside, but that part of the reflection was blocked by his own image. In a burst of bravado, he turned and looked into the car. And wondered, calmly enough, if he might be hallucinating. Because there were two of them in there.