Attila the Hun (30 page)

Authors: John Man

Tags: #History, #General, #Biography & Autobiography, #Historical, #Ancient, #Rome, #Huns

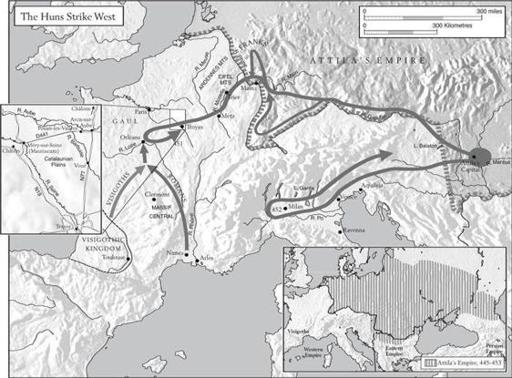

And now, with little time to spare, Aetius sent messengers to every major city and every barbarian clan that had found new land and new life in Gaul. The greater threat of Attila’s Huns won new allies: the Swabians of Bayeux, Coutances and Clermont, the Franks of Rennes, the Sarmatians of Poitiers and

Autun; Saxons, Liticians, Burgundians and other clans of yet greater obscurity; even some of the wild Bagaudae from Brittany. Many had their own insights into Attila’s progress, for traders brought news, and barbarian clans had friends and relatives fighting for Attila. Information leaked back and forth – so it was not too surprising that Aetius heard of Sangibanus’ offer to side with Attila in the coming siege of Orléans.

A

fter the Roman and barbarian armies linked up, somewhere unrecorded, they raced the Huns to Orléans, a race that Aetius won by a whisker, a day perhaps, or more likely several days, with enough time to suck Sangibanus, the vacillating Alan chief, into his ranks and ‘cast up great earth-works around the city’.

Some say that the Huns beat them to it, which is unlikely, but it made a great story that continued the drama of Anianus, now back in the city after his frantic journey to Arles.

With the Huns at the very gates and the townspeople prostrate in prayer (of course, this being a Christian account), Anianus twice sends a trusty servant to the ramparts to see if help is coming. Each time he returns with a shrug. Anianus despatches a messenger to Aetius: ‘Go and say to my son Aetius, that if he does not come today, he will come too late.’ Anianus doubts himself and his faith. But then, thanks be, a storm brings relief from the assault for three days. It clears. Now it really, really is the end. The town prepares to surrender. They send a message to Attila to talk terms.

Terms? No terms, he says, and sends back the terror-stricken envoys. The gates are open, the Huns already inside when there comes a cry from the battlements: a dust cloud, no bigger than a man’s hand, recalling the coming relief from drought in Elijah – the Roman cavalry, eagle standards flying, riding to the rescue. ‘It is the aid of God!’ exclaims the bishop, and the multitude repeats after him, ‘It is the aid of God!’ The bridge is retaken, the riverbanks cleared, the invaders driven from the city street by street. Attila signals the retreat. It was of course the very day – remembered as 14 June – that Anianus had given Aetius as the deadline.

1

Such a close-run thing makes good Christian propaganda, and therefore is not much favoured by historians. But it may contain an element of truth, because Sidonius mentions it, and he was a contemporary. Writing to Anianus’ successor, Prosper, in about 478, Sidonius refers to a promise he had made the bishop to write ‘the whole tale of the siege and assault of Orléans when the city was attacked and breached, but never laid to ruins’. Whether or not the Huns were actually inside the walls when Aetius and Theodoric arrived, there can be no doubt that their arrival saved the city. The event would remain bound into the city’s prayers for over 1,000 years, St Agnan’s bones being revered until they were burned by Huguenots in 1562, at which point the city gave its

affection to its even more famous saint, Joan of Arc, who had saved it from the English in another siege a century before.

In a sense, it didn’t matter whether Attila actually assaulted the city or not. His scouts would have told him of the city’s newly made defences and its coming reinforcements. There was no bypassing Aetius and the Goths; no chance of easy victory against this well-fortified city; no succour from Sangibanus, after all; nothing for it but a strategic withdrawal from the Loire’s forests to open ground, where he could fight on his own terms.

A

week and 160 kilometres later, the Huns approached Troyes once again, the wagons trailing along the dusty roads, the foot soldiers forming a screen over the open countryside, the mounted archers ranging all around, and Aetius’ army hungry on the flanks, awaiting its moment.

There had to be a showdown, and the place was perhaps dictated by an encounter between two bands of outriders, pro-Roman Franks and pro-Hun Gepids leading the way in the retreat. They met and skirmished, possibly near the village of Châtres, which takes its name from the Latin

castra

, a camp. Châtres is on the Catalaunian Plains, the main town of which was Châlons – Duro-Catalaunum in Latin (‘The Enduring Place of the Catalauni’) – and the coming battle is often referred to by later historians as the Battle of Châlons. In fact, Châlons is 50 kilometres away to the north; Latin sources closer to the time refer to it as the Battle

of Tricassis (Troyes), 25 kilometres to the south, which, they say, was fought near a place called something like Mauriacum (spellings vary), today’s Méry-sur-Seine, just 3 kilometres from Châtres.

Now it was time for a decision. Attila was on the defensive, and his army tiring. Which was better: to risk all in conflict, or continue the retreat to fight another day? But there might not be another day. An army retreating through hostile territory was like a sick herd, easy prey. Besides, to cut and run, even were it possible, was no way for a warrior to live, certainly no way for a leader to retain his authority. Was this perhaps the prophesied moment of national collapse, from which young Ernak would rise as the new leader? His shamans would know. Cattle were slaughtered, entrails examined, bones scraped, streaks of blood analysed – and disaster foretold. The shamans had some good news among the bad. An enemy commander would die. There was only one enemy commander who mattered in Attila’s eyes: his old friend and new enemy, Aetius. So Aetius was doomed. That was good, for ‘Attila deemed the death of Aetius a thing to be desired even at the cost of his own life, for Aetius stood in the way of his plans’. And how was Aetius to die if Attila avoided combat?

Attila had with him an immense throng of semi-reliable contingents from subordinate tribes, and his unwieldy, essential wagons full of supplies. But he also had the Hun weapon of choice, his mounted archers. If he could strike fast, as late as possible in the day, the onset of night could allow a chance to regroup and fight on the next day.

It was 21 June, or thereabouts, 1500 hours. The battle-ground was the open plain by Méry, which undulates away eastwards and northwards. The Huns would have to avoid being forced to the left, where they would be trapped by the triangle of waters where the Aube and Seine came together. They would fight as the Goths had at Adrianople, with a defensive laager of wagons acting as a supply base, and mounted archers launching their whirlwind assaults on the heavily armed opponents. The Huns put their backs to the river, and faced the pursuing Roman armies as they spread out over the plain. Attila placed himself at the centre, his main allies – Valamir with his Ostrogoths and Ardaric with his Gepids – to left and right, and a dozen tribal leaders ranging beyond waiting for his signal.

On the Roman side, Aetius and his troops took one wing, Theodoric and his Visigoths the other, with the unreliable Sangibanus in the middle.

Across the gentle undulations of the plain, all of this would have been in full view of both sides, and each would have seen the strategy of the other. Attila would hope his archers would break through the Roman centre; Aetius would hope his two strong wings could sweep in behind the archers and cut them off from their supply wagons.

Just nearby the plain rose in one of its slight billows, offering an advantage, which perhaps Attila had not spotted soon enough. When he did, and ordered a troop of cavalry to seize it, Aetius was ready. Aetius, either by chance or by shrewd planning, was closer. The

Visigoths, with cavalry commanded by Theodoric’s eldest son Thorismund, reached the summit first, forcing the Huns into a hasty retreat from the lower slopes.

First round to Aetius. There was nothing for it but a frontal assault. Attila regrouped, and addressed his troops, in a brief speech (in Hunnish, of course) that Jordanes, a Goth, quotes in Latin as if verbatim. It’s fair to conclude the king said something, and perhaps the words were indeed remembered and found their way into folklore; but Jordanes was writing a century later, when the Huns were long gone, so what Attila actually said is anyone’s guess. If Attila recalls Henry V here, it is Shakespeare’s version, not the real thing. Here’s the gist:

After you have conquered so many peoples, I would deem it foolish – nay, ignorant – of me as your king to goad you with words. What else are you used to but fighting? And what is sweeter for brave men than to seek vengeance personally? Despise this union of discordant races! Look at them as they gather in line with their shields locked, checked not even by wounds but by the dust of battle. On then to the fray! Let courage rise and fury explode! Now show your cunning, Huns, your deeds of arms. Why should Heaven have made the Huns victorious over so many, if not to prepare them for the joy of this conflict? Who else revealed to our forefathers the way through the Maeotic marshes, who else made armed men yield to men as yet unarmed? I shall hurl the first spear. If any stand at rest while Attila fights, that man is dead.

The words cannot be genuine, of course. Jordanes was keen to capture something of the fight-to-the-death spirit that has infused warriors down the ages: the Sioux’s battle cry ‘Today is a good day to die!’, Horatius in Macaulay’s Victorian epic (‘How can man die better than by facing fearful odds?’), and the ageing Anglo-Saxon who urged his fellows on against the Vikings at the Battle of Maldon in 991:

Courage shall grow keener, clearer the will,

The heart fiercer as our heart faileth.

And the battle itself? Jordanes rose to the occasion, with grand phrases that echo in the evocations of many battles in many languages. In translation, it even falls easily into free verse:

Hand to hand they clashed, in battle fierce,

Confused, prodigious, unrelenting,

A fight unequalled in accounts of yore.

Such deeds were done! Heroes who missed this marvel

Could never hope to see its like again.

A few telling details with the smack of truth survived the passage of time, pickled by folklore. A stream ran through the plain, ‘if we may believe our elders’, that overflowed with blood, so that parched warriors slaked their thirst with the outpourings of their own wounds. Old Theodoric was thrown and vanished in the mêlée, trampled to death by his own Visigoths or (as

some said) slain by the spear of Andag, an Ostrogoth.

2

Dusk was falling, on the evening of what could have been the year’s longest day. The whirlwind tactics of the Hun archers had not had enough impact on the Roman and Visigothic lines, which forced their way forward, breaking the Hun mounted formation, slashing their way into the rear lines protecting the wagons. Surrounded by his personal guard, Attila pulled back through the heaving lines to the circle of wagons that formed a wheeled fortress in the rear. Hard behind him, through the gap, came Thorismund, who got lost in the gloom and thought himself back at his own wagons, until a blow on the head knocked him off his horse. He would have died like his father, if one of his men had not hauled him to safety.

With the coming of night, the chaos stilled. Troops found comrades and settled into scattered camps. The night was fine: if it had rained, Jordanes would surely have mentioned the fact. But there were, I think, clouds, because it would otherwise have been a peculiarly dramatic sight. It would have been lit by a half-moon, as we know from the tables of lunar phases. Consult Herman Goldstine’s

New and Full Moons 1001

BC

to

AD

1651

,

3

and you learn that the new moon had fallen on 15 June, a week before the battle. So imagine a balmy summer night, darkened by cloud, ghostly figures, the snorts of horses, the clank and creak of armour, the groans of the wounded. Men mounted and on foot wandered in search of comrades, unable to tell friend from foe unless they spoke. Aetius himself was lost among the Huns, unnoticed by them, until his horse, stumbling over corpses, came to a Goth encampment and delivered him to safety behind their wall of shields, and perhaps to a couple of hours’ sleep for the rest of the short night.

There is something else that Jordanes does not mention. The early-morning twilight should have witnessed a wonderful sight – Halley’s Comet rising in the north-east, tail first, like a searchlight scanning the sky ahead. It was there all right, as astronomers have known since the orbit of Halley’s Comet was accurately calculated in the mid-nineteenth century. Since then calculations have been refined.

4

The comet was noted by Chinese astronomers on 9 or 10 June, and became visible in Europe by 18 June. A vision like this would have imprinted itself on the minds of warriors as sharply as an arrowpoint, for nothing would more forcefully have marked the significance of the occasion. Many other sightings did. In their cuneiform records, Babylonian astrologers remarked that the comet’s appearance in 164

BC

and 87

BC

coincided with the death of kings. Embroiderers stitched it into the Bayeux Tapestry to record its appearance when William the Conqueror invaded England in 1066. In the early fourteenth century, Giotto painted its 1301 return into

his

Adoration of the Magi

. Surely, if it had been seen, men would have marvelled, and written, and sung.