Austerlitz: Napoleon and the Eagles of Europe (31 page)

Read Austerlitz: Napoleon and the Eagles of Europe Online

Authors: Ian Castle

Tags: #History, #Europe, #France, #Military, #World, #Reference, #Atlases & Maps, #Historical, #Travel, #Czech Republic, #General, #Modern (16th-21st Centuries), #19th Century, #Atlases, #HISTORY / Modern / 19th Century

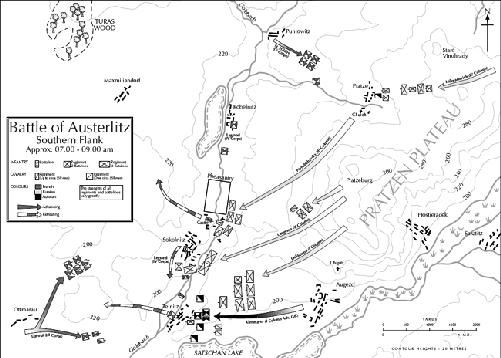

Weyrother ended his instructions by stressing that the columns should commence their movement at 7.00am, an hour before sunrise, and emphasised that once they had secured their first objectives in the Goldbach valley, they were to align themselves with their neighbouring columns before wheeling northwards.

Having listened to everything Weyrother had to say Langeron spoke up: ‘General, this is all very well, but if the enemy anticipate this and attack us near Pratze, what will we do? That scenario is not covered.’ Weyrother replied: ‘You

know the audacity of Bonaparte; if he was able to attack us, he would have done it today.’

Langeron then referred to the great illumination seen in the French camps earlier and questioned its significance. In response, Weyrother assured him that it must either signal that the French were retreating or moving back to a new position. In either case, the Austrian chief of staff asserted, ‘the orders remain the same.’

9

It was 3.00am before Weyrother finished, at which point Kutuzov, who had taken no part in the meeting, finally stirred and dismissed the commanders back to their columns. But Kutuzov was no fool – it seems likely that he listened carefully to all that was said. He did not want to fight a battle now, and having been removed from the decision making process, he had no intention of being blamed for any defeat, which he sensed would follow. Only now could Maior Toll begin making a copy of Weyrother’s orders in Russian. Around him a number of adjutants hovered impatiently while he completed his task: only then could they begin to recopy them for distribution to their columns.

Podpolkovnik Ermolov recalled that an officer arrived at his camp and handed a copy to General-Adjutant Uvarov. It ran for several pages:

‘filled with difficult names of villages, lakes, rivers, valleys, and elevations and it was so complicated that it was impossible either to understand or remember them. He was not allowed to copy them, because a lot of other officers had to read it, and there were very few copies. I have to admit that after I listened to this disposition I had as little comprehension of it as if I was not aware of its existence; the only thing that I understood was that we were supposed to attack the enemy tomorrow.’

10

But Ermolov was one of the lucky ones: some officers did not see the orders until about 8.00am, and by then the battle was already underway.

Langeron visited his outposts at a little after 4.00am and recorded that the ‘deepest silence reigned everywhere, the darkness was impenetrable and I could discover nothing’.

11

Across the Goldbach, in the French lines, Général de brigade Paul Thiébault was preparing his division for the coming battle. His men gathered ‘in the greatest silence under a clear and freezing sky’.

12

But during the early hours of the morning a thick winter’s fog settled in the valley of the Goldbach, drawing a veil all along the entire French front line, behind which the army completed its arrangements unobserved by the Allies.

FML Kienmayer, the Austrian commander of I Column’s advance guard, was first to move on the morning of 2 December, his task, to clear the village of Telnitz for the advance of Dokhturov’s main body. He knew the lie of the land well following his recent reconnaissance patrols, and with his outpost having been thrown out of Telnitz, he expected it to be vigorously defended.

The small village on the eastern bank of the Goldbach was surrounded by vineyards and ditches, making it well-suited for defence, and it lay sheltered behind a small hill interposed between it and Kienmayer’s men.

At 6.30am, in the pre-dawn darkness, Kienmayer advanced from Augezd, probing tentatively forward with the 1. Szeckel-Grenzregiment. These tough soldiers from Siebenburgen (now Transylvania in Romania), on the turbulent frontier of the Habsburg Empire, had only joined Kienmayer’s command the previous day, under Generalmajor Carneville. The leading battalion closed on Telnitz with the regiment’s other battalion in support. Detachments of French light cavalry (GB Margaron’s brigade, including Lieutenant Sibelet’s 11ème Chasseurs à cheval) were observed towards Menitz and on the high ground west of Telnitz. To oppose these, Kienmayer sent a detachment towards Menitz and formed the 4. Hessen-Homburg-Husaren to the right of the

grenz

infantry and the 11. Szeckel-Husaren to their left as protection against cavalry attacks. The 2. Szeckel-Grenzregiment stood further back in reserve with a single battalion of the 7. Brod-Grenzregiment from Slavonia.

In front of them, defending the hill shielding Telnitz, and in the ditches that surrounded the village, waited the weak battalion of the Tirailleurs du Pô, possibly supported by elements of the Tirailleurs Corses. These two battalions of foreign troops, from Italy and Corsica, would experience a long and distinguished career in the French army, but for now the ravages of campaign had taken their toll and between them they mustered less than 900 men. However, behind them a battalion of 3ème Ligne hastily prepared the village for defence, while the remaining two battalions of this regiment stood behind the village in support. In all, some 2,500 infantry, supported by about 1,000 light cavalry as well as artillery, waited for Kienmayer’s attack.

Against these men the single

grenz

battalion, about 600-strong, advanced in silence. It was still dark as they approached the hill, led forward by Oberst Knesevich, but as they came into view, the

tirailleurs

lining the crest opened a devastating fire. Soldiers were falling all around and the supporting cavalry suffered too, but they maintained their position on the flanks. It came as a rude awakening to those who anticipated only light opposition along the Goldbach.

With casualties mounting, the battalion of 1. Szeckel fell back, seeking what cover it could in the vineyards. Seeing the attack grind to a halt, Kienmayer ordered the supporting battalion of the regiment forward. Twice these battalions advanced together up the hill and both times a murderous defensive fire repulsed them. The entire success of the Allied battle plan now depended on I Column leading the way across the Goldbach, so Kienmayer ordered Majorgeneral Stutterheim to lead a new attack. This time the 1. Szeckel succeeded and the

tirailleurs

fell back to occupy positions along the stream towards Sokolnitz. Only now did the Austrians realise the extent of the task confronting them as below, barricaded in the village, the 3ème Ligne awaited their assault.

Kienmayer ordered Carneville to bring forward the other three battalions of

grenz

infantry to support the attack. The Austrians now committed some 3,000 men to the attack on Telnitz, but as the reserve moved forward, they passed through the bodies of hundreds of casualties from the initial attacks. A number of attacks rolled forward and one almost reached the village, causing the defenders to commit their reserve: stubbornly fighting for every wall, tree and ditch, the French infantry threw the Austrians back.

It was now about 7.30am and the battle had been underway for about an hour, but to Kienmayer’s surprise, the main body of Dokhturov’s I Column was still not in sight. The two Szeckel regiments, supported by the Brod battalion, continued to make fresh attacks on the village, but they lacked the urgency and determination of their earlier forays. Then, out of the lifting early morning gloom, the head of Dokhturov’s column came into view. It had finally emerged from the chaos and confusion which reigned on the plateau, as each of the allied columns struggled to assemble their men in the dark prior to their advance on the Goldbach.

Kienmayer sent a message to Buxhöwden, overall commander of the left wing, requesting urgent assistance. General Leitenant Fedor Fedorovich (Friedrich Wilhelm) Buxhöwden, a 55-year-old Estonian, had joined the army as a cadet officer at fourteen. He married well and through his wife’s connections, had entered the Russian court, making quick promotion through the officer ranks. Langeron, who served under him and had an axe to grind, later described his commander as, ‘the perfect emblem of stupidity and self-importance,’ adding that he was a ‘rather good subordinate officer … but as a general no one was more incapable of being commander-inchief.’

13

However, Buxhöwden responded promptly to Kienmayer’s plea and hurried forward General Maior Löwis’ brigade: a single battalion of 7. Jäger and all three battalions of the New Ingermanland Musketeer Regiment. The

jäger

advanced straight up the hill to join the Szeckel infantry, while the musketeers formed a reserve behind them on the level ground. Together, the

jäger

and two of the Szeckel battalions stormed down on Telnitz, followed by the other three

grenz

battalions. The sight proved too much for the battered 3ème Ligne, who abandoned Telnitz before they could be overwhelmed and regrouped just over half a mile back on a rise by the road to Ottmarau.

Kienmayer quickly ordered his cavalry to push on beyond the village and probed towards a low plateau occupied by Margaron’s cavalry. The two mounted bodies skirmished but neither side gained any advantage. Buxhöwden remained immobile some distance back, with Dokhturov and his two remaining infantry brigades. Holding this position he peered northwards searching for any sign of II and III Column: a necessary condition before contemplating an advance beyond the Goldbach.

Buxhöwden was not the only one awaiting developments. A mile away, across the frozen lake in Satschan, some of the villagers gathered and watched nervously from the church tower as the battle for Telnitz developed:

‘We were terrified by the noise of a very raucous fight between advance guards on the fields over Telnitz and Augezd … There were more and more shots, and when dawn finally broke, the first cannon shot hummed from Augezd Hill, by the small Chapel of St Antonin, and after that, a second shot rang out, followed by yet a third. After this, very intense gun fire started, so loud and rapid you could not separate one shot from another, and cannon shots thundered in brief succession. The ground shook and the tower itself seemed to tremble with us. We all turned pale and looked to each other silently, because we were unable to speak with the fear we were feeling. Finally, when the bright day began, it was possible to see many deep rows of soldiers, who were running against each other on the fields between Telnitz and Augezd. Eventually, smoke and dust completely clouded the horrifying theatre that surrounded us, and one could only hear the thundering of cannons, the clatter of muskets, and the war cries of the soldiers.’

14

Up on the Pratzen Plateau the situation in the camps was indeed chaotic. Having arrived after dark and grabbed what rest they could, the column commanders attempted to form up their men before daybreak, prior to marching them towards destinations they could not see, and for which many officers still had no orders. At about 6.00am Langeron, commanding II Column, discovered the Russian cavalry of V Column amidst his men. They had misunderstood their orders and should not have even been on the plateau. Amongst the milling mass of cavalry and infantry Langeron located General Leitenant Shepelev and informed him that he should be 11/2 miles to the north. In response, Shepelev assured Langeron that Prince Liechtenstein had ordered him to this position, adding that if in the wrong, he would move at daybreak, as he did not know where to go in the darkness.

15

The black winter sky began to lighten just before 7.00am. At this signal Langeron prepared II Column to move off the plateau and descend towards the Goldbach. Langeron formed his men behind 8. Jäger, the only unit under his command to have battle experience. Following the

jäger

came a company of pioneers, then Olsufiev’s infantry brigade (the Vyborg, Permsk and Kursk Musketeer Regiments) with Kamenski I’s infantry brigade (Ryazan Musketeer and Phanagoria Grenadier Regiments) forming the rear of the column. Just as 8. Jäger began to move off, the Russian cavalry that had appeared on the plateau an hour earlier recognised their mistake, and having reformed, began to march off, cutting right through II Column. Langeron halted his men and stood with

increasing impatience for about an hour as the cavalry moved slowly through his formation: then, deciding enough was enough, he pushed his men straight through their mounted comrades, thus adding to the confusion.

These delays meant Langeron was already roughly an hour behind schedule when he finally moved forward at around 8.00am. But Kamenski’s brigade, bringing up the rear of the column, again found their path blocked by the cavalry, who presumably did not take kindly to Langeron’s actions.

As his column moved slowly down from the plateau, Langeron observed I Column holding a position on his left while Kienmayer’s advance guard cleared Telnitz. Drawing level with I Column, Langeron rode over to speak to Buxhöwden, who was only 300 paces away. He advised the commander of the army’s left wing that there was no sign of III Column yet, which should have appeared on his right by now. III Column, commanded by General Leitenant Przhebishevsky, another foreign officer in Russian service who Langeron felt ‘was not a distinguished general and had set his sights too low to be useful, but was a brave and honest man’, had also suffered disruption at the hands of the cavalry. Having cleared Langeron’s camp, the horsemen progressed through that of Przhebishevsky, north-east of Pratze village.