Austerlitz: Napoleon and the Eagles of Europe (37 page)

Read Austerlitz: Napoleon and the Eagles of Europe Online

Authors: Ian Castle

Tags: #History, #Europe, #France, #Military, #World, #Reference, #Atlases & Maps, #Historical, #Travel, #Czech Republic, #General, #Modern (16th-21st Centuries), #19th Century, #Atlases, #HISTORY / Modern / 19th Century

It was now time to take a closer view of the battle and oversee the next stage. Accordingly, Napoleon ordered the relocation of his headquarters to the newly captured height of Staré Vinohrady.

___________

*

Colonel Pierre-Charles Pouzet, 10ème Légère, to Général de division Saint-Hilaire.

Chapter 15

‘We Are Heroes After All, Aren’t We?’

*

While Vandamme’s division dispersed the final remnants of IV Column from the plateau, Saint-Hilaire’s battle for control of the Pratzeberg still raged. At about 11.00am Langeron, still personally involved in the fighting, received word from adjutants despatched from IV Column, advising him with stark simplicity of the collapse of this force. Langeron ordered these messengers to pass on the shocking news to Buxhöwden, who remained inactive about a mile away on the hillock overlooking the Goldbach. Having been away from the rest of his command, fighting in Sokolnitz, for an hour and a half, and with no sign of help coming from Buxhöwden, Langeron realised he must find reinforcements himself. Leaving Kamenski to continue the fight, Langeron galloped off back to Sokolnitz.

At around the same time Weyrother, Kolowrat and Kutuzov approached the Pratzeberg, following the defeat of the other half of IV Column, doing their best to encourage the Austrian troops. Kutuzov, accompanied by a staff officer, Prince Dmitry Volkonsky, then reached Kamenski’s brigade just as it was in danger of being broken by a French attack, but Volkonsky rallied the Phanagoria Regiment by grasping their standard and leading them forward: order was again restored.

As Langeron headed off to find reinforcements, the Austrian battalions recovering from their attack on Thiébault’s line reformed within reach of Kamenski’s brigade. Their brigade commander, Jurczik, anchored his position on a small rise, where he concentrated some of his artillery. Major Mahler brought his battalion of IR49 Kerpen to the rise and drew the battalion of IR58 Beaulieu in to protect the flank. At the same time he moved two guns to a position from where they could enfilade the French line, which brought their fire to a halt for a while. Jurczik applauded his actions shouting, ‘Bravo! Major

Mahler!’

1

Shortly afterwards Jurczik fell to the ground, fatally wounded by a French musket ball. He died two weeks later.

Once the Austrian battalions had recoiled from the French artillery, Thiébault joined his men with the rest of the division and together they attacked Kamenski’s brigade, driving them back and capturing a number of limbered Russian guns as well as retaking their own previously lost guns. Their impetus took them right to the summit of the Pratzeberg, and it was only with some difficulty that the officers managed to control the ardour of their men and halt the line. In fact, the infantry had now left their supporting artillery behind and with no word from Maréchal Soult or imperial headquarters, Saint-Hilaire felt his isolation keenly.

2

Recognising the urgent need to drive the French off the plateau, and aware of their current exposed position, the Allies prepared to make:

‘a general and desperate attack at the point of the bayonet. The Austrian Brigade, with that under General Kamenski, charged the enemy; the Russians shouting, according to their usual custom; but the French received them with steadiness, and a well-supported fire, which made a dreadful carnage in the compact ranks of the Russians.’

3

But the Russians pressed on. Thiébault, close to the centre of the action, watched as the Russians:

‘charged on all sides, and while desperately disputing the ground, we were forced back. It was only by yielding before the more violent attacks that we maintained any alignment among our troops and saved our guns … Finally after an appalling melee, a melee of more than twenty minutes, we won a pause; by the sharpest fire and carried at the point of the bayonet.’

4

According to the notes kept by Thiébault, this ‘twenty minute bayonet battle’, claimed the lives of both Colonel Mazas, 14ème Ligne, and Thiébault’s ADC, Richebourg. Thiébault was fortunate to escape injury himself when his horse fell to a Russian shot.

5

But as both sides recovered their breath, Général de division Saint-Hilaire rushed up to his brigade commanders, Thiébault and Morand, saying: ‘This is becoming intolerable, and I propose, gentlemen, that we take up a position to the rear which we can defend.’ Almost before he finished speaking, Colonel Pouzet of the 10ème Légère interrupted: ‘Withdraw us, my General … If we take a step back, we are lost. We have only one means of leaving here with honour, it is to put our heads down and attack all in front of us and, above all, not give our enemy time to count our numbers.’

6

Pouzet’s stirring words did the trick, and reinvigorated, the French clung tenaciously to the ground they held, repelling all Russian attacks.

While the Russians doggedly continued to attack, the Austrian battalions were being pressed back, despite the best efforts of Weyrother and Kolowrat. Having reformed close to a small rise, supported by their artillery, the battalions reformed and engaged the 36ème in a firefight, halting an enemy advance with volley fire. However, the French recovered and attacked again, driving IR58 Beaulieu back. Mahler attempted a counter-attack with his battalion of IR49 Kerpen and that of IR55 Reuss-Greitz but reported coming under ‘a very severe fire’ that caused many casualties. With his left flank now exposed to attack due to the repulse of IR58, his position was becoming extremely dangerous. However, he managed to keep his men together and prevented them from falling back for a while with the help of his adjutant, Fähnrich Jlljaschek. Moreover, by maintaining volley fire, he was able to remove his wounded safely to the rear.

But elsewhere, the Austrians were gradually being forced back. Mahler started the battle with only 312 men in his battalion and was now reduced to around eighty, through casualties and men lost as prisoners. There was little more his tiny force could achieve and as the battalion of IR55 on his flank began to retreat he ordered his men away down the eastern slopes of the plateau.

7

The odds were now stacked against Kamenski’s resolute brigade as more French troops approached the Pratzeberg. Released by Vandamme, the 43ème Ligne moved to rejoin Saint-Hilaire’s division and Boyé’s brigade of cavalry (5ème and 8ème Dragons) was also on its way to add their support. The weight of French numbers now began to tell on the Russian line. On his left, the threat of an attack on his open flank by the French dragoons forced Kamenski to wheel back the extreme left-hand battalion of the Ryazan Musketeers. Having soaked up all the preceding Russian attacks, Saint-Hilaire, judging that the time was right, ordered the French line forward, in what turned out to be the decisive charge. This time Kamenski’s men had little left to offer as the French poured forward over ‘ground strewn with the dead’, leaving no wounded Russians in their wake, capturing the Russian battalion artillery and retaking the highpoint of the Pratzeberg. Yet even in this moment of victory on the Pratzeberg the Russians inflicted another notable casualty: Saint-Hilaire was wounded and forced to retire to Puntowitz to have his wound dressed.

8

Having arrived back at Sokolnitz, Langeron sent for General Maior Olsufiev, who was fighting in the village and informed him of the need to send reinforcements to the plateau. The only troops immediately to hand were the two battalions of the Kursk Musketeers, held in reserve just outside Sokolnitz. With no time to lose, Langeron directed these to the plateau. He then attempted to extract his other battalions from the village but only succeeded in pulling back 8. Jäger and the Vyborg Musketeers. The remaining battalion of Kursk Musketeers and the Permsk Musketeer Regiment, now so completely entangled with III Column and its battle for the village, could not be

withdrawn. But even as the two Kursk battalions began their march, unknown to them, they were marching to their destruction.

Kutuzov recognised that any further resistance by Kamenski’s brigade, after two hours fighting, would lead to their total destruction, so he ordered the retreat. Abandoning the plateau, they descended the south-eastern slopes to the valley of the Littawa, where they reformed. All along the valley other Allied units that had been driven off the plateau took up defensive positions or retreated to better ground. Before he left the plateau, Kutuzov despatched a hurried note to Buxhöwden, who still had not moved, ordering him to extract his three Columns from their bottleneck and retire. Soult’s two divisions were complete masters of the Pratzen Plateau, having swept away Allied IV Column along with Kamenski’s brigade of II Column by the sheer determination of their attacks. The time was probably around noon when, into this killing ground, marched the two lone battalions of the Kursk Musketeers, sent from Sokolnitz.

Believing the troops ahead of them to be Russian, they approached confidently but as they closed, Thiébault turned his exhausted men to face them and another firefight exploded. At the same time, Lavasseur’s brigade of Legrand’s division (IV Corps), which was occupying Kobelnitz, marched southwards presenting a possible flank threat to the Kursk battalions. To combat this move, the Podolsk Musketeers, part of III Column reserve, advanced to oppose them. Even without this intervention, the French troops on the Pratzeberg were in overwhelming numbers and soon began to surround the isolated Kursk battalions, who fought on for a while before collapsing amidst massive losses.

The victorious Thiébault, now mounted on his third horse – a small grey liberated from a captured Russian artillery limber – surveyed the destruction all around him. His own brigade had lost about a third of its strength, while another of his regimental commanders, Houdard de Lamotte of the 36ème Ligne, joined the growing list of wounded.

While this final struggle to clear the Allies from the Pratzen Plateau had reached its climax, elsewhere on the battlefield matters were also coming to a bloody conclusion.

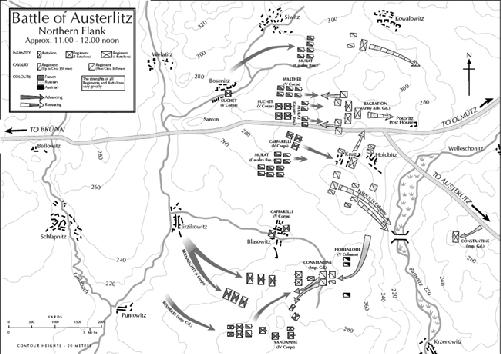

Grand Duke Constantine, at the head of the Imperial Guard, had received no orders since a request arrived for him to send a battalion of infantry up onto the plateau. Since then his Guard Jäger had fallen back from Blasowitz, along with a supporting battalion of Semeyonovsk Guards. With only limited military experience, Constantine considered his options. To his right, masses of French infantry and cavalry were pressing aggressively towards Bagration, while to his left the Austrian cavalry, which had offered some protection on that flank, were withdrawing, having temporarily held back the advance of a massed infantry formation (Rivaud’s division of Bernadotte’s I Corps). Further to the

left, up on the plateau, he could see that the French were driving back at least part of IV Column. Having surveyed the position, Constantine elected to pull back to his left rear (south-east), towards the Austrian cavalry and hopefully a junction with a reforming IV Column somewhere near Krzenowitz. At around 11.30am he turned his force, deploying the Guard Jäger as a flank guard.

In fact, he had not moved very far when he realised that the French troops previously held in check by the Austrian cavalry were now slowly advancing towards him. Up until now, Bernadotte had shown a marked reluctance to move forward since he crossed the stream at Jirschikowitz earlier that morning. Napoleon sent his aide, de Ségur, to ensure that Bernadotte carried out his orders, but the imperial messenger found the commander of I Corps agitated and anxious. Bernadotte indicated the Austrian cavalry to his front and bemoaned the fact that he had no cavalry of his own with which to oppose them, begging de Ségur to return to Napoleon and obtain some for him. De Ségur did as he requested but Napoleon had none to offer. However, now that the Austrian cavalry had withdrawn, Bernadotte cautiously advanced his corps, Rivaud edging slowing forward between the plateau and with Blasowitz to his left front, while Drouet led his division onto the lower slopes of the plateau in support of Vandamme.

Aware now of this forward movement, Constantine halted the Guard and faced them to confront this new threat. Behind him, the single bridge over the Rausnitz stream represented a very dangerous bottleneck. To gain time for his crossing, Constantine decided to strike a blow at the advancing French in an attempt to halt their advance. Forming the two Guard fusilier battalions from both the Preobrazhensk and Semeyonovsk Regiments for the attack, he held back the battalion of Izmailovsk Guards in reserve and organised the cavalry in a supporting role. Hohenlohe’s three Austrian cavalry regiments took up positions protecting the left and right rear of the Russian Guard: 5. Nassau-Kürassiere to the left with 1. Kaiser and 7. Lotheringen-Küirassiere to the right. The four battalions leading the attack advanced with much confidence, roaring ‘Oorah! Oorah! Oorah!’ and when still 300 paces from the opposing French line, they broke into a run that their officers were unable to control. Although facing a withering barrage of musketry, the Russian guardsmen did not halt and smashed straight through the first line of massed skirmishers, pushing them back onto a formed second line of infantry, which they attacked with the bayonet. These too gave way, but although elated with their success, the Russian attack ground to a halt and when French artillery opened up on them they began to fall back in disorder.

9

But the threatening presence of the Russian Guard cavalry prevented any attempt at pursuit and kept Rivaud’s division firmly anchored to the spot.