Austerlitz: Napoleon and the Eagles of Europe (43 page)

Read Austerlitz: Napoleon and the Eagles of Europe Online

Authors: Ian Castle

Tags: #History, #Europe, #France, #Military, #World, #Reference, #Atlases & Maps, #Historical, #Travel, #Czech Republic, #General, #Modern (16th-21st Centuries), #19th Century, #Atlases, #HISTORY / Modern / 19th Century

Russia remained unaffected by the Treaty of Pressburg and Napoleon hoped to draw the tsar into an alliance against Britain but he failed. Instead, Russia sided with Prussia, joining Britain and Sweden in a Fourth Coalition. The Russian army was too far away to assist Prussia when Napoleon attacked in 1806, and as a consequence, was obliged to maintain the struggle with limited Prussian support the following year. After a bloody draw at Eylau, the subsequent French victory at Friedland settled the war leading to a temporary alliance between France and Russia.

The condition Austria found itself in at the end of the war is clearly illustrated in a gloomy letter written a few days after the signing of the Treaty of Pressburg by Archduke Charles to his brother the kaiser:

‘Austria faces a terrible crisis. Your Majesty stands alone at the end of a short but horrible war; your country is devastated, your treasury empty … the honour of your arms diminished, your reputation tarnished and the economic well being of your subjects ruined for many years.’

11

Austria now embarked on a period of military reform, with Archduke Charles at the helm. But the kaiser could never dismiss his feeling of suspicion towards Charles, leading to numerous court intrigues; which in turn affected the implementation of his reconstruction. Although experiencing much pressure to align the Austrian army with Prussia in 1806, Charles wisely avoided committing to the cause. In 1809 Austria rose again against Napoleon, burning to avenge her losses in 1805, but although repulsing Napoleon at

Aspern-Essling, defeat in the subsequent battle at Wagram forced Austria to sue for peace.

On the eve of the departure of the Russian army from Hollitsch the tsar dismissed GM Franz Weyrother, his Austrian chief of staff. Langeron felt that the tsar was ‘finally disgusted’ with him.

12

Burdened with the stress of defeat and suffering from the effects of the huge responsibility and workload that fell to him during the campaign, Weyrother became ill and withdrew to Brünn where he died a few weeks later, on 16 February 1806, aged fifty-two.

Also in February, FML Mack faced court martial for his capitulation at Ulm. The trial lasted until June 1807 and the resulting judgement stripped him of his rank, withdrew his Maria Theresa Order and sentenced him to two years imprisonment. On his release in 1808 Mack settled to life as a virtual recluse. Later, in 1819, after the dust had finally settled on a Europe ravaged by war, his rank was reinstated and his Maria Theresa Order restored at the request of Feldmarschall Schwarzenberg. At Ulm, fourteen years earlier, Schwarzenberg had been one of the officers who abandoned Mack, leaving him to his fate by riding out of the city with Archduke Ferdinand. Mack died aged seventy-six in 1828.

And what of Charles Schulmeister, Napoleon’s ‘Emperor of Spies’? He left Vienna on 14 January 1806 and returned home a rich man. He invested his fortune in a large château at Meinau near Strasbourg. But despite this wealth, Schulmeister craved the

Legion d’Honneur

, an award Napoleon denied him, saying, ‘The only reward for a spy is gold.’ Schulmeister rejoined Savary in the war against Prussia in 1806 where, besides carrying on an extremely effective espionage campaign, he succeeded, at the head of thirteen cavalrymen, in capturing the town of Wismer and its garrison of 500 men. In 1807, at the Battle of Friedland, Schulmeister received a wound from a bullet that cut across his forehead leaving a prominent scar. At the conclusion of the campaign, with his fortune further enhanced, Schulmeister returned to Meinau and invested the money in developing his estate. Savary called for Schulmeister again in 1809, when the rewards of the campaign enabled him to purchase another château and property in Paris, but he also entertained lavishly and spent unwisely, building up extensive debts. Then, in 1814, when the Allies drove Napoleon back into France, the Austrians issued an arrest order for Schulmeister and his two chateaux were ransacked by the Prussians, forcing him into hiding. After the Waterloo Campaign, Schulmeister was captured by the Prussians and imprisoned in the fortress of Wesel but bought his freedom at vast cost, the figure variously reported but at the least £1.4 million in current terms. Schulmeister remained under surveillance by the Bourbons until 1827, during which time he invested in a series of business enterprises that invariably failed, forcing him to sell off his properties one by one to ease the debts. Finally, in 1843, he sold off his last asset, the château at Meinau, leaving him penniless. Five years later, when Schulmeister had attained the grand age of

seventy-eight, a former comrade, now the minister of finance, took pity on him. He arranged a tobacco kiosk concession for him in Strasbourg that granted him a small income for the next five years until his remarkable life came to an end in 1853, caused by a swollen artery of the heart. He outlived all the central characters of this story.

The Treaty of Pressburg destroyed the Third Coalition by withdrawing Austria from the war. The original plans of the signatories called for flanking attacks in Hanover and the Kingdom of Naples in which British troops would participate. Accordingly, Swedish and Russian troops arrived in Swedish Pomerania early in October and advanced on Hanover. In mid-November a British army joined them, having sailed from England two days after the receipt of news of Mack’s surrender at Ulm. Prussia also sent troops into Hanover but the prevarication of Frederick William in joining the coalition caused confusion and prevented the pursuit of decisive action against French forces occupying Holland. When news arrived of Austerlitz and of the treaty concluded between Prussia and France, as well as that between Austria and France, Allied troops began to draw back from their forward positions. By February 1806 they were embarking for home.

At the same time the Anglo-Russian force detailed to land in the Kingdom of Naples arrived only belatedly, in early January 1806, and learning of Austerlitz abandoned the plan, re-embarking a few days later.

In London, the prime minister, William Pitt, had waited expectantly for the positive results from the coalition he had done so much to bring together and finance. The news that Napoleon had abandoned plans to invade Britain and was marching to face the armies of Austria and Russia brought him great relief, but this was followed by the shocking details of Mack’s defeat at Ulm, which reached him on 3 November. However, the arrival of full details of the great naval victory of Trafalgar four days later lifted his mood again. On 9 November, at the Lord Mayor’s banquet in London, guests fêted the prime minister as the ‘Saviour of Europe’. In response he declared, ‘Europe is not to be saved by any single man. England has saved herself by her exertions, and will, as I trust, save Europe by her example.’ It was his last public speech.

Pitt had suffered from ill health all his life and now the stresses and strains of office were taking their toll on him, as were crippling debts and an addiction to port wine. On 7 December he left London for Bath, to ‘take the waters’, in the hope that it might benefit his constitution. It was here that he received the crushing news of Austerlitz. This, followed by the destruction of the coalition brought about by Austria’s treaty with France and the failure of the Allied expedition to Hanover, conspired to weaken his spirit dramatically. He returned to his home in Putney Heath in London on 11 January. As he entered his house he pointed to a map of Europe and with great foresight announced, ‘Roll up that map, it will not be wanted these ten years.’ Two days later a

meeting to discuss bringing the army home from Hanover seemed to drain him even further and a friend who visited on 15 January observed that ‘his countenance is extremely changed, his voice weak, and his body almost wasted’. The following day he took to his bed and on 23 January, William Pitt, the implacable opponent of Napoleonic France and leading architect in the creation of the Third Coalition, died. His last words embodying the failure he felt in his heart: ‘Oh my country! how I leave my country!’

In Paris, Napoleon stood victorious, casting his long shadow of dominance over Europe. But peace did not follow. Within a few short months he would again unsheathe that finally honed weapon, La Grande Armée, and cast it towards Prussia. It was the beginning of a sanguinary journey that was to last almost ten years: a journey that would cost the lives of many thousands of men, and finally end on the rolling, muddy fields of Waterloo.

___________

*

Count Alexander Suvorov (1729–1800), Russian Field Marshal.

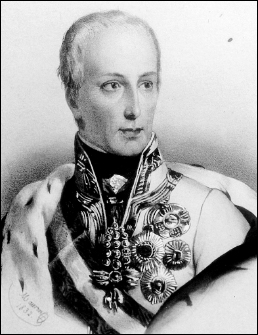

Francis I came to the Habsburg throne in 1792 and for the next twenty-three years led Austria through the turbulent period of the Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars. In 1804 he gave up the title ‘Kaiser Francis II of the Holy Roman Empire’ and took in its place that of ‘Kaiser Francis I of Austria’.

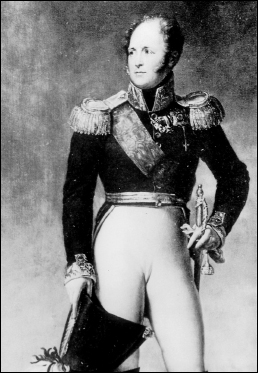

Tsar Alexander I succeeded his murdered father, Paul I, in 1801 at the age of twenty-three. A grandson of Catherine the Great, he saw himself as the arbiter of Europe, once his initial admiration for Napoleon waned.

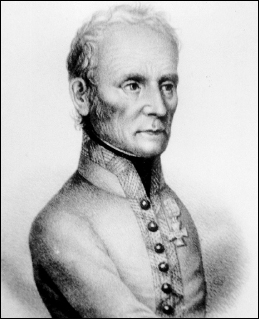

Karl Mack, de facto commander of the Austrian army that marched into Bavaria. Mack was appointed chief of staff to Archduke Ferdinands’s army, but carried secret authority from the kaiser allowing him to overrule the young archduke.

Mikhail Kutuzov, the commander of the Russian forces. Although exiled from St Petersburg prior to the commencement of the campaign and not consulted on the Russian strategy, he agreed to lead the army into Bavaria.

(Sammlung Alfred und Roland Umhey)