B004R9Q09U EBOK (2 page)

Authors: Alex Wright

For all the barrels of ink and billions of pixels spent chronicling the rise of the Internet in recent years, however, surprisingly few writers seem disposed to look in any direction but forward. “Computer theory is currently so successful,” writes philosopher-programmer Werner Künzel, “that it has no use for its own history.”

9

This relentless fixation on the future may have something to do with the inherent “forwardness” of computers, powered as they are by logics of linear progression and lateral sequencing. The computer creates a teleology of forward progress that, as Birkerts puts it, “works against historical perception.”

10

My aim in writing this book is to resist the tug of mystical techno-futurism and approach the story of the information age by looking squarely backward. This is a story we are only beginning to understand. Like the narrator in Edward Abbott’s

Flatland

—a two-dimensional creature who wakes up one day to find himself living in a three-dimensional world—we are just starting to recognize the contours of a broader information ecology that has always surrounded us. Just as human beings had no concept of oral culture until they

learned how to write, so the arrival of digital culture has given us a new reference point for understanding the analog age. As McLuhan put it, “one thing about which fish are completely unaware is the water, since they have no

anti-environment

that would allow them to perceive the element they swim in.” From the vantage point of the digital age, we can approach the history of the information age in a new light. To do so requires stepping outside of traditional disciplinary constructs, however, in search of a new storyline.

In these pages I traverse a number of topics not usually brought together in one volume: evolutionary biology, cultural anthropology, mythology, monasticism, the history of printing, the scientific method, eighteenth-century taxonomies, Victorian librarianship, and the early history of computers, to name a few. No writer could ever hope to master all of these subjects. I am indebted to the many scholars whose work I relied on in the course of researching this book. Whatever truth this book contains belongs to them; the mistakes are mine alone.

I am keenly aware of the possible objections to a book like this one. Academic historians tend to look skeptically at “meta” histories that go in search of long-term cultural trajectories. As a generalist, I knowingly run the risks of intellectual hubris, caprice, and dilettantism. But I have done my homework, and I expect to be judged by professional standards. This work is, nonetheless, fated to incompleteness. Like an ancient cartographer trying to draw a map of distant lands, I have probably made errors of omission and commission; I may have missed whole continents. But even the most egregious mistakes have their place in the process of discovery. And perhaps I can take a little solace in knowing that even Linnaeus, the father of modern biology, was a devout believer in unicorns.

I am a firm believer that without speculation there is no good and original observation.

Charles Darwin, Letter to A. R. Wallace, 1857

When the Spanish conquistadores first encountered the Zuni people of the North American southwest, they noticed something strange about their villages. The tribe had divided each of its six “pueblos” (as the Spanish called them) into a set of identical quadrants, aligned with the four points of the compass. Each quadrant housed a troop of clans within the larger tribe: The clans of the Crane, the Grouse, and the Evergreen lived in the north; the clans of Tobacco, Maize, and Badgers lived in the south. Each clan enjoyed a set of special relationships with the natural world. To the people of the north belonged wind, winter, and the color yellow. The people of the west knew water, spring, and the color blue. The people of the north made war. The people of the west kept the peace. When the villagers sat together, they sat apart, like hawks and doves. To the four cardinal directions, the Zuni added three vertical ones: the sky, the earth, and a middle realm in between. In the sky, all the colors of the world swirled together; down below, the earthen realm was black. In the middle, everything came together; heaven and earth were joined. To one of these seven directions the Zuni assigned everything in the cosmos: animals, natural elements, supernatural forces, social responsibilities, families, and individual members of the tribe. This all-

encompassing system equipped the Zunis with a taxonomy of the natural world, a social and political system, a mythology, and a framework for spiritual belief.

1

The Zuni system represents one people’s solution to a problem we all share: how to manage our collective intellectual capital. For more than 100,000 years, human beings have been collecting, organizing, and sharing information, creating systems as varied as the cultures that produced them. Along the way, we have invented a panoply of different tools: taxonomies, temple archives, books, libraries, indexes, encyclopedias, and, in recent years, computer networks.

Today, we live in an age of exploding access to information, awash in what designer Richard Saul Wurman calls a “tsunami of data.” Human beings now produce more than five exabytes

*

worth of recorded information per year: documents, e-mail messages, television shows, radio broadcasts, Web pages, medical records, spreadsheets, presentations, and books like this one. That is more than 50,000 times the number of words stored in the Library of Congress, or more than the total number of words ever spoken by human beings.

2

Seventy-five percent of that information is digital. Most of it will soon disappear. Amid this welter of bits, perhaps some of us worry, like Plato’s King Thamus, whether our dependence on the written record will weaken our characters and create forgetfulness in our souls.

As the proliferation of digital media accelerates, we are witnessing profound social, cultural, and political transformations whose long-term outcome we cannot begin to foresee. Organizational charts are flattening, as electronic communication tools enable employees to bypass old chains of command; national borders are growing more porous, as networked data flows across old boundaries; and long-established institutional knowledge systems (like library catalogs) are fast becoming anachronisms in the age of Web search engines. Wherever networked systems take root, it seems, they disrupt the old hierarchical systems that preceded them. Indeed, a faith in the death of

hierarchy has become a durable nostrum of the digital age. In the popular 1999 tract

The Cluetrain Manifesto

, the authors proposed a credo for the Internet age: “hyperlinks subvert hierarchy.”

3

That sentiment captures the widely held belief that the rise of the Internet signals the permanent disruption of old institutional bureaucracies and the birth of a new, enlightened age of individual expression: a renaissance of creativity and personal freedom. In this utopian view, hierarchical systems are restrictive, oppressive tools of control, while networks are open, democratic vehicles of personal liberation. When networks triumph over hierarchies, then, humanity takes a great leap forward.

This comforting narrative is, alas, too tidy by half. Networked information systems are not entirely modern phenomena, nor are hierarchical systems necessarily doomed. There is a deeper story at work here. The fundamental tension between networks and hierarchies has been percolating for eons. Today, we are simply witnessing the latest installment in a long evolutionary drama.

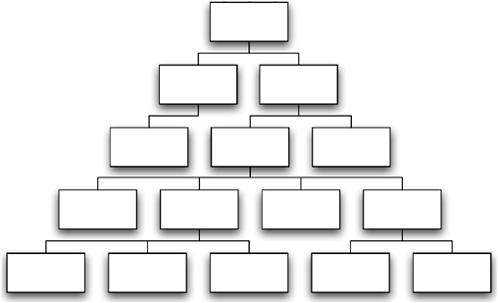

Since the words “network” and “hierarchy” will recur throughout this book, let me spend a moment with the terms. A hierarchy is a system of nested groups. For example, an organization chart is a kind of hierarchy, in which employees are grouped into departments, which in turn are grouped into higher-level organizational units, and so on. Other kinds of hierarchies include government bureaucracies, biological taxonomies, or a system of menus in a software application. Computer scientist Jeff Hawkins suggests that human memory itself can be explained as a system of nested hierarchies running atop a neural network.

4

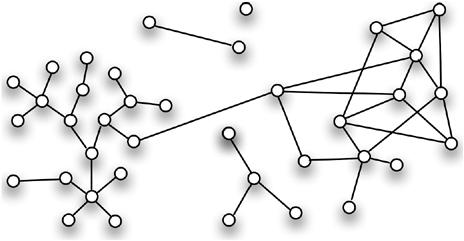

A network, by contrast, emerges from the bottom up; individuals function as autonomous nodes, negotiating their own relationships, forging ties, coalescing into clusters. There is no “top” in a network; each node is equal and self-directed. Democracy is a kind of network; so is a flock of birds, or the World Wide Web.

Networks and hierarchies are not mutually exclusive; indeed, they usually coexist. We might, for example, work for a company with a formal organization chart; at the same time, we probably also maintain a personal network of colleagues that has no explicit representation in the formal organization: a network within a hierarchy.

Similarly, the Internet—ostensibly a pure network—is actually composed of numerous smaller hierarchical systems. At its technical core the Internet works by breaking large groups of data into small packets, tiny hierarchical units of information stored on a server which are then dispersed across the network and reassembled in a client application, such as a Web browser. At a higher level, much of the content of the Web is generated within organizational hierarchies—like companies, educational and nonprofit institutions, and government agencies—as well as by ostensibly self-directed individuals who nonetheless rely on hierarchical organizations (like computer manufacturers or service providers) to participate in the network. And for all the seeming flatness of the global Internet, most of us make sense of the Web in hierarchical terms: by navigating through menus on a Web site, for example, or selecting from a narrow list of search results. In other words, networks and hierarchies not only coexist, but they are continually giving rise to each other.

Hierarchy

Network

Science writer Howard Bloom has suggested that the tension between networks and hierarchies is not an exclusively human phenomenon, but part of a deeper process embedded in the fabric of the universe itself, stretching all the way back to the Big Bang.

5

We needn’t look quite so far back, however. Two billion years will do.

While our reliance on networked information systems may seem like an acutely modern dilemma, we are not the first generation—nor even the first species—to wrestle with the problem of information overload. The information age started not with microchips or movable type, but with the first flowering of complex life. To approach the history of information systems from a purely human-centered perspective is to overlook the lessons of billions of years’ worth of evolutionary history. Just as our brains carry around some very old reptilian equipment, so our collective strategies for managing information bear the traces of patterns that took shape long ago.

John Locke famously argued that “beasts abstract not.” But in

recent years, thanks to the breakthrough work of geneticists and evolutionary psychologists, we are beginning to appreciate the surprising complexity of nature’s nonhuman information systems. The animal world is rife with examples of organisms developing collective strategies for accumulating, storing, and distributing information in groups. An assertion like that seems to beg for a definition of the word “information,” so let me offer one:

Information is the juxtaposition of data to create meaning.

If we accept the familiar construct of information as lying on a continuum from data to wisdom (data > information > knowledge > wisdom), then there is no question that other animals create, share, and organize information. And while animal minds may not harbor the abstractions of human thought, they frequently employ information-pooling strategies that bear startling resemblances to our own.