B004R9Q09U EBOK (6 page)

Authors: Alex Wright

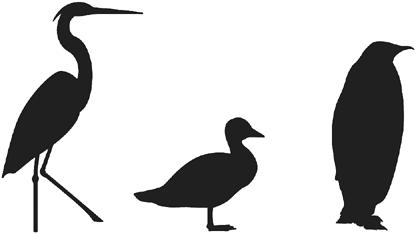

Psychologist Eleanor Rosch pioneered prototype theory, a breakthrough model of human cognition that predicts how the mind assigns things to categories not only based on cultural information but through a process of direct sensory engagement with the phenomenal world. Her theory suggests that people form categories based on “prototypes,” or best examples of a particular kind of thing. The theory explains, for example, why people in different cultures tend to recognize similar types of colors or similar kinds of animal species. For example, consider the following pictures of birds (see facing page). If you had to select one of the images below as the best example of a “bird,” which one would you choose?

Chances are, you would pick the second image as the best example of a “bird.” The crane on the left is taller than most birds; the penguin on the right cannot fly; but the bird in the middle is similar in size and shape to most other kinds of birds, so it falls closest to the best example or prototype.

Prototype theory suggests that we have not only an innate disposition toward categories, but also that we have an ability to iden

tify levels of gradation within those categories. This capacity for gradation—that is, the ability to recognize that things may be both different and similar at the same time—holds the key to our capacity for hierarchical categorization. One-dimensional categories are inherently dissatisfying to the human brain; we seem to have an innate need to separate things into finer-tuned distinctions. As a result, we form nested categories to describe the relative similarities and differences between things. In all likelihood, folk taxonomies evolved in concert with our cognitive facility for hierarchical categorization.

Rosch’s work has, alas, been widely misinterpreted. A simplistic reading of her research would suggest that categories are determined through perception alone—that is, that there are categories inherent in the world. Rosch herself even subscribed to this view in her early work, giving rise to much of the subsequent misinterpretation. But she later revised her theory, coming to the conclusion that prototypes themselves do not determine the semantic categories that people formulate; rather, these are determined through a more complex process of cultural transmission. “Prototypes do not constitute a theory of representation for categories,” she wrote. “The facts about prototypes can only constrain, but do not determine, models of representation.”

6

In other words, the categories themselves are transmitted through culture, but the human brain is born ready to receive the transmission.

In his landmark book

Women, Fire and Dangerous Things

, lin

guist George Lakoff wrote a sweeping refutation of the classical (or objectivist) view of categories. The classical view stems from the Aristotelian notion of things having intrinsic characteristics, ideal forms. It is predicated on the possibility of universal truth based on the observation of derived properties. This approach served as the foundation of the modern scientific method and Linnaean taxonomy; it would later run afoul of findings in evolution. Classical categories proceed from disembodied ideals and support the notion that ideas inhabit another plane of thought.

To question the classical view … is thus to question the view of reason as disembodied symbol-manipulation and correspondingly to question the most popular version of the mind-as-computer metaphor. Contemporary prototype theory does just that—through detailed empirical research in anthropology, linguistics, and psychology.… [H]uman categorization is essentially a matter of both human experience and imagination—of perception, motor activity, and culture on the one hand, and of metaphor, metonymy, and mental imagery on the other. As a consequence, human reason crucially depends on the same factors. And therefore cannot be characterized merely in terms of the manipulation of abstract symbols.

7

Our capacity for categorization, in other words, has a biological basis, in terms of both individual cognition and our larger social interactions. Prototype theory also meshes seamlessly with Wilson’s theory of gene-culture coevolution. The human brain appears to have evolved in concert with the social transmission of categorical information. As a result, we are all born with a deep-seated need to understand the world in terms of categories and to share that understanding with each other.

Our long heritage of taxonomic thinking has influenced more than just the way we label plants and animals. For tens of thousands of years, these archetypal information systems weaved themselves into

the fabric of human social life. Folk taxonomies became deeply entwined with the first mythologies, taking on progressive layers of meaning that became embedded in our cultural heritage. In 1903 the sociologist Emile Durkheim, along with his colleague Marcel Mauss, published a pioneering study of the larger social role of folk taxonomies entitled

Primitive Classification

. In one of the first studies of its kind, Durkheim surveyed the taxonomic practices of aboriginal peoples in Australia and North America. His research led him to probe the little-understood relationship between classification systems and human social organization.

Durkheim posited that the structure of classification systems hewed closely to the structure of existing family and kinship networks, expressing a deep unconscious need for members of tribal societies to project their otherwise inscrutable kinship relationships onto the outside world. When people described the natural world, therefore, they did so by invoking the language of family relationships: Plants and animals belonged to “families.” The fir tree was the child of the category “tree,” the sibling of the pine, and perhaps a distant cousin of the bush, but it was no relation to a chicken. Tribal conceptions of the natural world paint the animal kingdom as one big interlocking web of families. Thus, natural classification systems reflected existing kin relationships; the vastness of the natural world provided a kind of conceptual mirror that allowed tribe members to ponder the larger web of connections among themselves.

In Australia, Durkheim observed how aboriginal tribes classified the natural world using a system that meshed seamlessly with their own tribal organization. Each tribe was divided into “moieties,” or social units, each of which in turn was subdivided into so-called marriage classes, and further subdivided into smaller clans. Each of these clans, in turn, claimed an affiliation with some natural element: the trees, the plains, the sky, the stars, the wind, the rain. Each clan also followed certain dietary restrictions according to their marriage class (members of one class ate opossum, kangaroo, dog, and honey, while members of another class ate emu, bandicoot, black duck, and certain snakes). Like the Zuni people (see

Chapter 1

), the aboriginal tribes used their own family structures as living containers for cat

egorizing information about plants, animals, and the natural elements.

8

Looking deeper into the symbolic relationships between family organizations and the associated animals and elements, Durkheim discovered the correlation between family subdivisions and the ethnobiological ranking systems. “In fact the moiety is the genus,” he wrote. “The marriage class is the species; the name of the genus applies to the species,” and so forth. “We are no longer dealing with a simple dichotomy of things,” wrote Durkheim, “but with hierarchized concepts.” For these remote tribal societies, Durkheim came to the conclusion that the structure of early human classifications reflects macro social structures, projections of human social relationships. The two systems reinforce each other—indeed, in the “primitive” mind they are indistinguishable.

The first categories may have emerged as outward expressions of existing social relationships: an attempt to make visible otherwise invisible relationships like “parent,” “sibling,” or higher-level abstractions like “family.” As Hobart and Schiffman write, “Genealogy provides the ideal classificatory tool, for it narrates a sequence of actions. It thus sustains the tradition while, at the same time, subjecting it to a hierarchical ordering that clarifies the nature of various figures. When gods are considered, genealogy becomes a means of understanding the cosmos … when mortals are considered, it becomes an encyclopedic framework for historical and geographical as well as social information.”

9

Durkheim believed that the tendency toward categorical hierarchy simply reflects the natural hierarchy of family structures, thus explaining the prevalent human tendency to describe groups of plants and animals in kinship terms. The family tree, in other words, works as a two-way metaphor: Families are shaped like trees, and trees are shaped like families. “The first logical categories were social categories; the first classes of things were classes of men, into which these things were integrated. It was because men were grouped, and thought of themselves in the form of groups, that in their ideas they grouped other things, and in the beginning the two modes of grouping were merged to the point of being indistinct.” So in Durkheim’s

view, categories derived from existing social structures, forming a conceptual template into which the tribes poured their knowledge about the natural world. “Moieties were the first genera; clans, the first species. … It is because human groups fit one into another—the sub-clan into the clan, the clan into the moiety, the moiety into the tribe—that groups of things are ordered in the same way.”

10

If tribal classifications do indeed represent externalized projections of social relationships, it seems fair to surmise that these systems must also entail some level of emotional investment. These systems succeeded because they tapped into the reinforcing power of human emotion by mirroring existing family relationships. If we accept Greenspan’s assertion that higher-order information exchange relies on emotional triggers in our limbic system (see

Chapter 1

), then we could accept Durkheim and Mauss’s assertion that “a species of things is not a simple object of knowledge but corresponds above all to a certain sentimental attitude.”

11

Berlin, however, questions Durkheim’s conclusions about the social origins of taxonomies: “[T]he ethnobiological data suggest strongly that [Durkheim and Mauss] were wrong in their proposal on the social origins of classification. My strong intuition is that it was just the other way around; knowledge of natural kinds and the similarities and differences between and among species provided the model for the social classifications that humans ultimately constructed to provide meaning to social relations.”

12

In other words, perhaps people did not create taxonomies to mimic the structure of social relationships; instead, they modeled their social relationships after their observations about the natural world. Regardless of which came first—the human family or the taxonomic one—there is no question that taxonomies and human social structures evolved in concert with each other.

Multilayered, socially pregnant taxonomies would eventually find a complex and beautiful expression in advanced mythological systems like those found in Greece, China, and elsewhere, where systems of astronomy, astrology, geomancy, and divination merged into complex, highly stylized classification systems with deep taxonomic roots. The Chinese folk classification centers on the division of space into four cardinal points, each of which is further divided in two, resulting

in eight compass points that, like the Zuni system (see

Chapter 1

), represent the natural elements: heaven, earth, clouds, fire, thunder, wind, water, and mountains. For example, the south is associated with the father principle, as well as with sky, pure light, force, the head, heaven, jade, metal, ice, red, and horses. In opposition to the fatherly south stands the motherly north, associated with earth, darkness, docility, cattle, the belly, and cloth, among other things. Thus, the basic genealogical principle of mother and father expands into a broad classification system framing the Chinese people’s understanding of the world. Each direction is also associated with a season (each of which is further subdivided into six, making for the 24 seasons of the Chinese calendar), an animal (the dragon to the east, red bird to the south, white tiger to the west, and black tortoise to the north), a color, an element, and certain underlying principles.

13

The classification of natural phenomena into eight categories resembles the strategies employed by other human cultures that developed oceans away: The Australian Aborigines, Zunis, and numerous other human societies have developed analogous systems relying on the correlation of cardinal directions with seasons, animals, elements, and genealogical relationships.

The Chinese astrological calendar also has deep taxonomic roots, connecting each year in a 12-year cycle with a totemic animal: rat, cow, tiger, rabbit, dragon, snake, horse, goat, monkey, rooster, dog, and pig. The animals divide into four groups of three, each associated with a compass direction and with one of four natural elements (fire, water, earth, wind). Thus the entire classification system pulls together an integrated worldview, encompassing time, geography, the animal kingdom, and elemental forces. As Durkheim and Mauss put it, “Here we have, then, a highly typical case in which collective thought has worked in a reflective and learned way on themes which are clearly primitive.”

14

The guiding principles of Chinese classification provided the philosophical framework guiding everything from architecture (as in the well-known practice of

feng shui

) to affairs of state, personal relationships, and the Chinese conception of the natural world. Over a period of several thousand years, Chinese civilization became a living manifestation of a vast and all-encompassing

classification system. The Chinese system provides perhaps the most compelling example of an ancient classification that survived and adapted itself through long periods of upheaval: wars, empires, and the emergence of a vast institutional bureaucracy.