B004YENES8 EBOK (14 page)

Authors: Barney Rosenzweig

I tried, having impressed Ms. Smith and Mr. Crais with my editorial acumen on episode one, to push my luck by getting them to visualize, prior to editorial, how what they were writing was actually going to play—what the realistic constraints of time and budget might do to their creative vision. There was a scene with Tyne Daly and an octogenarian in a wheelchair (yes, we were back to that). I would point out how static this nearly six-page sequence would appear on film. April would tell me how the moves with the wheelchair would be “choreographed.”

I knew how little money we had for sets. I knew our budget called for shooting eight to nine pages of dialogue per day. This woman was defending giving a five-and-a-half-page scene to an actor well past his professional prime (especially in terms of memorization of reams of material), keeping one of the finest actresses on television in a passive, reactive mode, and then had the hubris to talk to me about

choreography

! I threw up my hands. It was our third episode.

“Shoot it your way,” I said. “Maybe you’ll learn something.”

The less-than-six-page scene took an entire day of production. It was all the actor could do to remember two sentences back to back, let alone any wheelchair choreography. It’s just as well, for by the time we partially furnished the set and added two actors and a camera, not even Evel Knievel could have maneuvered that wheelchair through the clutter in any way other than the basic forward and back.

If Ms. Smith learned anything, she kept it to herself. The work went on. The gang of four kept me involved to some extent because they needed me to fight their battles with the network and Orion. They felt director Reza Badiyi was not in tune with their literary efforts; they needed me to dismiss him and get Orion to pay off his multiple-episode guarantee.

What, one might well ask, was I doing? Why was I pussyfooting? Initially, it was because I was still at Paramount. I was an absentee executive producer. I came to hate that. More and more I heard myself sounding like Leonard Goldberg from my bad old days on

Charlie’s Angels

.

My notes on scripts continued to be largely ignored. I was getting angry. The irregular hours of the writing staff, their seeming reticence to listen to anyone but themselves, and their penchant for assigning themselves scripts or sharing credit with freelance writers who came to work on the show only increased my frustration.

I had worked too hard, and come too far, for this. By episode six I was in there with both feet. My agreement to leave Paramount had me, along with all other personnel, moving to Lacy Street by episode seven.

This, of course, was not April’s understanding of the way things would be, but at first she seemed to almost welcome the help. She waited nearly three weeks before having her ultimatum delivered to CBS: “It’s either him or me.”

I knew nothing of this when I appeared in the office of Kim LeMasters, who was then the CBS VP in charge of drama and one heartbeat away from Harvey Shephard’s job. He innocently asked me how things were going between April and myself.

I elected to be candid. I told him how talented I thought she was, but that working with her was difficult. I added that I understood how she might have trouble with me since she had originally been given to believe (by me) that I would serve in a merely advisory role. I added that I was cautiously optimistic that now that we were all physically together at the same plant, things might get better. That’s when Mr. LeMasters told me of Ms. Smith’s ultimatum. Before I could fully react, Kim added, “Harvey laughed.”

Of course. There was no way in the world CBS, or any company, would have responded favorably to such a threat. She had been on the job only a few months. I had conceived the project, produced a super-successful M.O.W., designed a series almost overnight, delivered those first episodes as promised (on what many believed to be an impossible schedule), taken a cancellation then turned it into victory, brought them Sharon Gless, as pledged, and given up a lucrative major studio deal to come to the aid of this series. In opposition was this producer-come-lately saying, “It’s him or me.”

It was funny. It was also pathetic and foolish.

Ultimately, had she been a little patient, it would all have been hers. I wasn’t going to stay. I couldn’t afford to. Orion was not prepared to meet the economic terms that I could get almost anywhere else in town. Not only was this a problem for them psychologically (for they knew me when …), it was a real fiscal barrier. The entertainment explosion of the early eighties was in high gear everywhere, save for this fledgling company. Fees for top creative personnel were growing geometrically.

My fee of $2,500 per episode (worked out in 1978–79 for my deal with Mace) was, at Paramount in 1981, $20,000 per episode and escalating each subsequent year. This was a reflection of the burgeoning economics of the syndication marketplace for one-time network programs then in reruns. Prices for these episodes were skyrocketing with no end in sight. As a result, major television companies would pay whatever they had to in order to assure themselves of more units for future syndication and to have the talent under contract to create and produce those units.

Orion was not a major television company; its new management team wasn’t even sure it wanted to be in television. They had already gotten rid of Iannucci and would keep Rosenbloom and his division only so long as he delivered on his guarantee of little or no deficits. That meant a lean and mean production plan, no fancy offices, and no highly paid creative personnel.

I liked my fancy offices at Paramount, the luxurious frills that accompanied any major studio deal, and my high fees. There was more. When Orion paid me one dollar, they had to pay Mace Neufeld fifty cents. Because of the settlement with Mace, I was actually more expensive than anyone else they might hire.

There was no way they were going to match what I could get elsewhere. I knew it and didn’t even ask. I would move into Lacy Street on a very temporary basis, exercise my contractual creative control, get this series on the right track, and then turn it over to April Smith. All this I would do for my $10,000 per episode non-exclusive executive producer’s fee—money Orion was contracted to pay for the life of the series even if I elected to move to Hawaii and sit on the beach leisurely reading scripts and commenting on them by trans-Pacific telephone. My offer to do the hands-on work for no additional compensation, even on a temporary basis, was thus most welcomed by all parties—save, of course, for the gang of four.

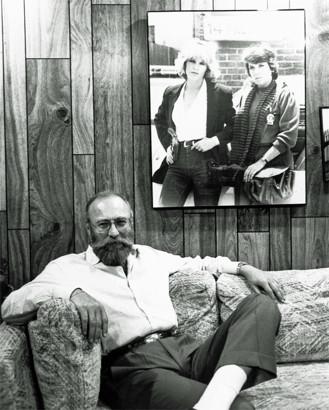

In my office at Lacy Street with my favorite photo of Sharon and Tyne in the background.

Photo: Rosenzweig Personal Collection

Chapter 17

COMINGS AND GOINGS

The crisis over April’s ultimatum was, as far as I was concerned, nonexistent. I continued on in a “business as usual” fashion, never mentioning the incident or acknowledging that I had even been told about it.

We were in production on episode eight, preparing and casting episode nine, cutting episode seven, spotting and dubbing episode six, and beginning our script meetings on episode ten.

The show had debuted with episode five to good reviews and not bad ratings. I would do my best to bury episodes two and three. “Stringing beads” or no, I was not going to open with weak material. Where necessary, we re-shot scenes to accommodate the new continuity imposed by this release pattern.

Despite industry-wide predictions that the show would fail—that Harvey Shephard had been victimized by his own hype—the ratings were more than acceptable, performing from 15% to 20% better than the previous inhabiter of the time period,

Lou Grant

. There was reason for optimism. I believed that at any time Harvey Shephard would phone and increase our order by nine additional episodes to the full season complement of twenty-two.

April’s original script for episode ten—the aforementioned “Recreational Use”— was excellent, tough, and sophisticated: Cagney romantically involved with a fellow officer from another precinct, a cop who used drugs “recreationally.” It was bold and uncompromising. Even the network asked for very few concessions, and, although I had yet to earn the kind of power I would eventually have, what fights I did have with the network for this material were largely and comparatively easily won.

Meanwhile, I had script notes of my own. My concerns were mostly for purposes of clarity. April’s writing style was sparser than I was used to. Ninety percent of my notes addressed the issue of this minimalist approach. I met with the gang of four in a small brick building we called the schoolhouse. It was adjacent to our Lacy Street factory complex and was used almost exclusively by the writers for their gang-bang approach to material.

I believe I’m good with script. It’s a subjective call, but one that I feel comfortable in making. Too many fine writers have endorsed this view for me to feel very modest about it. I have written, and do write. Basically, however, I do not consider myself a writer. I

am

a storyteller. I also feel I’m a friend of writers. I invariably (sometimes to the project’s detriment) work within the universe they have created. I do not generally throw out material and start speculating with a litany of what-ifs. My job, at least this part of it, was to try to get on the page the things that would help the reader, the director, the actor, the staff, and the crew, visualize and realize the concept for which the writer is striving.

In addition to feeling I’m good at it, I also believe I am a benign and friendly force. Not only am I noncompetitive, I am supportive. That’s my immodest belief. That’s my view of how I operate with writers. Imagine then my reaction when one or the other of April’s staff would, in support of their leader and in reaction to my notes, scoff or even titter at my comments.

“Scoff” and “titter” are not commonplace verbs in my vocabulary. They are the only terms I can conjure to portray the behavior to which I felt I was being exposed. My not understanding something or asking for clarity somehow seemed to make me a fool in their eyes. They had what appeared to be a sense of their own personal power (individually and cumulatively) that must have been somehow intoxicating. It was as if they were all “on” something, and April’s smiling, somewhat-girlish demeanor only served to encourage her minions.

We were midway through my comments and the writing staff’s titterings on “Recreational Use” when I excused myself from the schoolhouse and phoned April’s secretary, requesting that she tell her superior that I wished to see her in my office as soon as possible.

“It is to my eternal discredit,” I began my spiel to Ms. Smith, “that I allowed you to deride Barbara Corday, who, by the way, was instrumental in the creation of this series, and that in reaction to your behavior in this matter, I never said a word.” April was now in my office, sitting opposite my desk as I continued on, with deadly calm, giving no indication by action or inflection of my emotional state. I would leave it to my words to convey my sense of outrage.

“It is also reprehensible that I did, and said, nothing when you so trivialized Richard Rosenbloom that he will no longer even visit this plant. That I again did, and said, little when you drove Reza Badiyi (one of the sweetest men I know) to tears, is unforgivable. But now you have gone too far. You have finally insulted me, and I tell you, lady, that does not happen. Not in my store. Not on my show. Not from one of my employees.”

I left no room for a rejoinder. I don’t think she had one. I went on. “If you are operating from the illusory position that you have some kind of power around here, let me disabuse you of that. This is my schul,

26

and only at my pleasure are you allowed to worship here. Now, I want changes in this script. My notes are simple. If you cannot—or will not—do them, then I have a very fine writer standing by who will execute them this weekend. The choice is yours.”

Before she could speak I made an addendum. “Understand something: for however long you remain in my employ, you and I will meet privately in my office one-on-one. I will never again attend a meeting with your staff. They are unworthy of my time or patience, and I will expect drastic changes in that department in the very near future.”

“Can I take the weekend to think about this?” April wanted to know. “No,” I responded. “I will need this weekend to have the script reworked if you are not going to do it.”

“Even if I agree, I can’t be finished by the weekend,” she said.

“Can you have the first two acts by Friday?”

She nodded.

“That’s OK with me,” I said. “I can make a judgment from that just how seriously you are addressing my concerns.”

Two days later, Harvey Shephard called. We would be picked up for the full season. He was giving us an order for nine more episodes.

I had April and her staff join me in the squad room set, as I had the company hold up work on this first day of episode nine to inform them of the happy news: four more months of employment on a good-paying job for everyone. Good reason to celebrate. I then called the attention of all gathered to April Smith and her “fine staff,” who had done so much to bring us this far. Everyone applauded. I don’t believe I have talked to Frank Abatemarco or Jeffrey Lane since.

Back in the producer’s wing, we celebrated the pickup. April had her arm around my waist. I held her close and offered her champagne. She declined. She had a lot of work to do by Friday.

The threat that I had another writer in position to rewrite over the weekend was not an idle one. Ronald M. Cohen had agreed to work with me on the assignment should I need help. We had become quite good friends since our sojourn together on

American Dream

. I had been instrumental in getting him his new deal at Paramount, and, just prior to my decision to leave the studio, we were to work together on a project of his. Ronald had showed a friendly interest in

Cagney & Lacey

almost from the beginning, and we often talked of it. He was the one who had encouraged me to exhort the writers to search for, and explore, the moral dilemmas that would become a cornerstone of our series.

He was now a gun I did not have to use. April did the rewrite, addressed herself to all my notes, and easily accomplished 80 percent of them on her first go-round. Naturally, I was pleased. April was happy enough with the results on paper but not with our relationship. She tried different variations on her original ultimatum, first going to Rosenbloom with a proposal he would not even discuss. Then, with nowhere else to go, she elected to come directly to me.

She had a plan that called for a sort of production troika. She would be in charge of script with little or no input from anyone else. I was to supervise post-production, while the physical plan for the series itself, including casting, would be divided between April and Orion’s designee, as long as that person was not me.

My counter was that things go on as they had been with one important change. I would insist that Abatemarco and Lane not be renewed at the end of the first thirteen episodes and that April replace them for the back nine. I would be happy to continue with Crais, but that was her decision. This was unacceptable to April. Whatever we negotiated between us, her staff would have to remain intact. I was not negotiating. The gang of four was toast.

My adamancy about two of the foursome was multifaceted. It was necessary, in my view, to break up this offensive (to me, for openers) quartet. Still, I had hoped not to throw the proverbial baby out with the bathwater. Abatemarco and Lane were the most recent additions to the staff, the two I respected (by far) the least and—in my view—the most easily replaced. The fact that Abatemarco had a harder time altering one of his scripts to my notes, or those of the network, than any writer I have ever dealt with, and that Mr. Lane had involved us in a plagiarism suit over his most recent teleplay, might also have added to my equation.

The conversations went on for days. April and I were immutable on this one issue. She was loyal to her staff, and I simply would not put up with that group any longer.

Finally, a new element: April said if she could not control who was on her staff then she would ask that she be allowed to resign and that the option on her contract not be exercised for the back nine. I accepted her resignation with genuine regret.

Bob Crais was in my office minutes later. He, too, asked to be relieved of his contractual responsibilities. I tried to talk him out of it and even went so far as to offer him a directing assignment, which I knew he dearly coveted. He held firm. It’s possible these two thought they had me in a box. I like to think it was more than the old “nobody can write this show but me” syndrome. I felt these were principled people who believed in their duty to be loyal to their troops. I wanted Abatemarco and Lane out, and they did not. They were protesting this decision with the only power they had: the will to withhold services and give up their jobs.

Within an hour of all this, Frank Abatemarco’s agent was on the phone. She had heard that April and Bob would be leaving the series and wanted me to know of her client’s interest in continuing—provided he be given April’s position as writer-producer. The body wasn’t even cold. Loyalty among the gang of four, I observed, was very one-way.

I could not resist. I told April of the call and that I felt she was a fool to go to the mat for these guys who would not do the same for her. She refused to believe that I had not made up the whole thing.

The grave news of April’s departure went through our little company. One by one, the actors—then Dick Rosenbloom and even April’s husband, who came by to introduce himself—asked me to reconsider. I was clear with them all. April was welcome to stay. I wanted her to stay, but there was, and could be, only one boss on this show. That boss would be me.

Finally, Tyne and Sharon came in tandem to see me, requesting my rapprochement with Ms. Smith.

“Writers will come, and writers will go,” I began. “The same is true of directors, of crew and staff—even members of our acting ensemble. The only constants,” I went on, “are you and me. We are here for the duration. You have contracts, I have a vested interest unlike that of any mere employee. Get used to it, and get used to dealing with me, year in and year out. I will be here for you as you will be for me. That’s our deal. I will never say to you, ‘It’s only television,’ and you must never unfairly exploit your power over me by refusing to do your work. As long as that remains true, I will continue to use every possible moment and every bit of power I have, right up to the final edit, to make what we do deeper, richer, fuller, better.”

27

The war was over.

The next day at lunch, Harvey Shephard told Dick Rosenbloom and me of his pleasure at the success of the series thus far. We had averaged a 28 share against Monday Night Football and the NBC movies, and that was fine. I was learning to appreciate the value of being in a slot where the expectation level was not too high; I’ll take that any day and leave the inheritance of a 38 share to the other guys.

“You’ll get clobbered during February sweeps,” Shephard went on, “but if the show comes back in March and April to these kinds of numbers, I can guarantee a pickup for the fall.”

That afternoon, I met with the writing team of Steve Brown and Terry Louise Fisher. They had done a good job on

This Girl for Hire

and, now, for the first time, were considering doing episodic television. I had explored this with them several months before but had been turned down. Now they were ready. The deal was in place for them to join the

Cagney & Lacey

company with only the issue of credit still being open; they wanted to be called producers.

I pleaded with them not to press this issue. They had never done episodic television before, had never produced before. I told them how I felt personally about the proliferation of credits issue, how I would never go after their credit as writers and how multiple producers on a show leads to confusion on a production and, ultimately, hurt feelings (witness my very recent debacle with Ms. Smith).