B004YENES8 EBOK (20 page)

Authors: Barney Rosenzweig

It was some rare meeting.

I reported all this to Rosenbloom. He, too, was in disbelief. We agreed to keep all this to ourselves and to play out the hand to see what would happen.

The following Monday we were contacted by Metromedia , the station group that was responsible for keeping

Fame

alive after network cancellation. Orion’s Jamie Kellner, Dick Rosenbloom, and I were in their offices the day after that. Their first question was where had we been? They loved the show and were most anxious to put it on their stations. I glared across the room at Kellner. It was a terrific meeting, and the only question was would we be able to produce the show for the smaller dollars Metromedia had to offer? We promised to look into that and get back.

At 4:04 pm the following afternoon, Wednesday, September 21, 1983, Alan Levin, the senior VP in charge of business affairs for CBS, was on the phone. “Can you put it all back together again?”

I told him I believed it was possible. Levin was a business man, and this was a no-nonsense corporate kind of conversation. Six minutes later Harvey Shephard called. He was happy for me and gave me a sense of what was being talked about. An order of six or seven episodes, to be ready by spring, a protected time period, then—if all went well—on to the fall of 1984 with an order for twenty-two and success.

The summer of 1983 was over. For two weeks I had been operating under my new overall deal with Orion Pictures Corporation. My new deal, which did not anticipate the renewal of

Cagney & Lacey

as a series—a series, that two months earlier I could have purchased for maybe a dollar and a half. Had I had a single notion that such a renewal was possible, I certainly could have had Lee Rosenberg address it in my new deal—but who would have thought of such a thing?

I would not rain on my own parade as I focused back to that incredible call from CBS: “We have made a mistake; can you put it back together again?”

I drove over to Rosenbloom’s office in Century City. We would plunge immediately into the work. No time to celebrate. On arrival, I was told Bud Grant, Shephard’s boss from CBS, was on the telephone. He wanted this all finalized by the

Emmy

broadcast that Sunday. He believed we were going to win Best Series, and he had an image of me, “

Rocky

-like,” holding that statue aloft and making the announcement to the world that Cagney and Lacey were back. I told him I appreciated the imagery, but there was a lot to be done between now and then.

Rosenbloom and I huddled. Our presumption was that Sharon would be the stumbling block; after all, she was the one who hadn’t stopped working since the show’s demise. She would give up the most by returning to our series.

I wanted to get everyone in a room around a large conference table and hammer this out as if this were an international peace parlay. I was optimistic that there was a lot of goodwill here and that this nontraditional approach would work better than the conventional “us versus them” negotiating stance so common to labor/management talks. Rosenbloom turned me down. I backed off of this position but insisted on bringing in the agents for Tyne and Sharon.

At 5:30, Merritt Blake, Tyne’s agent, was there. He wanted to make it work but did not want to be stupid. I assured him that he and his client would be treated equally with Sharon and her agent, Ronnie Meyer. Meyer came in at 6:40. He’s a lot tougher than Merritt, though he conceded he wanted it to happen. That night I talked to both of the women, and it was clear to me that they were excited, happy, and wanted this to work out. Could it be done by Sunday?

The next day, Thursday morning, Tyne and I talked on the phone. “Barney,” she said, “it’ll work out, but it can’t happen by week’s end. There’s too much for me to think about.” I went to the office and called Rosenbloom.

“I don’t think we can settle this before the

Emmys

,” I said.

“You’re telling me!” he exclaimed, and then he read me Ronnie Meyer’s demands for Ms. Gless: a long list and very expensive. CBS was dismayed and Levin suggested pulling the offer, but Rosenbloom mollified him. We continued strategy meetings, trying to ascertain what we wanted, what the actresses would settle for, and what we could get from CBS. Those questions were put on the back burner that Friday morning when Army Archerd’s column in

Daily

Variety

revealed the whole story as his lead item.

We had pleaded with everyone for secrecy. We did not want this out prematurely because it effectively now let CBS off the hook. I had been quoted extensively in the press urging CBS to ask us back. Well, they had, and now the world knew it. The shoe was on the other foot—the ball, very much, in our court.

I did several phone interviews that day. We appeared nationally and locally on television with the news. I was attempting to sound encouraged while committing us to nothing and, at the same time, trying to maintain public support and not have us appear greedy.

I had a lovely lunch break with Tyne, complete with champagne, then on to a meeting at CBS to pitch a new project to drama VP Carla Singer, set up over a week before the

Cagney & Lacey

news. What a reception at the network! From Harvey Shephard, Carla Singer, and Tony Barr. The secretaries and assistants literally applauded as I walked down the hall.

The next morning I received a phone call from Mace Neufeld. “I have to read about this in the papers? You couldn’t call?”

I smiled as I paraphrased his comment to me of nearly two years before. “Mace, baby. It’s payday. What do you care? It’s only television.”

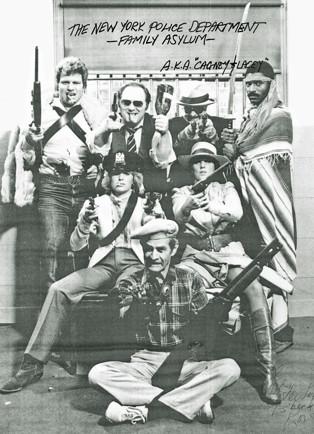

Halloween at Lacy Street. Everyone showed up with a Rosenzweig mask, including the award winner, who had earrings and lipstick added and was called Mary Beth Rosenzweig. This all led to editor Chris Cooke’s invention of “Barney, the Stick;” it was sort of a fly-swatter topped off with my picture and accompanied by the legend that one could take it to network meetings or battles with an in-law or whomever and be assured of … oh, I don’t know … something.

Photo: Rosenzweig Personal Collection

The gang in an attempt at humor. That is Sidney Clute in front, flanked by Sharon and Tyne with (from left) Marty Kove, Al Waxman, John Karlen, and Carl Lumbly. No one remembers now, but I am betting this was Kove’s idea.

Photo: Rosenzweig Personal Collection

Chapter 22

BACK BY POPULAR DEMAND

What was happening to me, or more precisely, to

Cagney & Lacey

, had never happened before. Sponsors had, in the fifties and sixties, brought back TV shows because some member of their board of directors liked what he or his spouse had seen. Bill Paley had resurrected a show every now and then because it was a personal favorite. One network had licensed another’s reject, in some desperate ploy to get out of the ratings cellar, or brought back one of its own out of an elongated hiatus, but this was different.

The sets for

Cagney & Lacey

had been dismantled or sold; its actors, writers, crew, and staff were no longer under any kind of contractual obligation. The show was over—except it wasn’t.

Cagney & Lacey

was brought back by popular demand.

Other forces were at work; CBS had lost over seventy million dollars that year in the cable business, forcing economies throughout the corporation, including program development. That made Mr. Shephard and his staff a lot needier in 1983 than they had ever been before. There was Gloria Steinem, who would publicly chastise Messrs. Paley and Wyman at CBS for their short-sightedness in prematurely ending the only dramatic show on television to feature women. There were those incredible ratings for the summer—all that press, the reviews, the nominations, and the letters. Harvey Shephard called it “an avalanche of mail”.

Now the monolith had been brought to its knees in the best David and Goliath tradition. It was a great story, and it has been retold many times. It took everything mentioned heretofore to pull it off, plus eleven weeks of the most grueling, emotional negotiations in which I have ever been involved.

Needless to say we did not get our announcement at the

Emmys

. First of all, Bud Grant’s fantasy required that the series win. It did not (

Hill Street Blues

won for the second year in a row), though Tyne Daly did for Best Actress in a Dramatic Series. Everyone around us at the ceremonies that Sunday was buzzing about the story published the previous Friday. Was it true? Would

Cagney & Lacey

be back on the air and, if so, when? Mostly we answered with knowing smiles.

I mentioned that all contracts with the artists were void; all save one: mine. My old deal on

Cagney & Lacey

was in place in perpetuity; my old deal, calling for me to work for $10,000 per episode (less than one half of my newly negotiated fees on any upcoming show, now memorialized in my new contract at Orion at $25,000 per episode); my old deal, with its measly share of profits and no mention of gross. My old deal, which called for my former associate and eternal nemesis, Mace Neufeld, to be tied to my fee structure and owning three times my share of the profits. My old deal, which no one seemed to remember, was only created in the first place to allow me just enough time to get the series up and running then pulling back to “clip coupons”.

Now we had an “opportunity” at CBS to audition yet again. I was, as far as anyone knew, still “of the essence.” I was the key to getting Tyne and Sharon to re-up. I was the guy who everyone acknowledged knew how to handle this show, and I was the guy now being asked to suspend his new deal (with all that terrific upside potential) at a time in his career when he had the most heat, in order to... what? Take a chance? To possibly sully that memory with a very minimal seven show order?

CBS had said they had made a mistake; they were not saying, “Come on, we’re going to make you rich.”

Cagney & Lacey

was the greatest come to me/go from me act in the history of network television. We had been rejected on a national scale, and now we—the actors and me—were being asked to forgive all that and come back and try out once again. Not only that, I was being asked to do it under an antiquated deal. I balked. I submitted that this new circumstance with CBS should fall under the terms of my new arrangements with Orion.

“What about Mace Neufeld?” they wanted to know. There was no way they felt they could accommodate my current pact plus his.

“Put

Cagney & Lacey

under my new deal, and I’ll take care of Mace out of my end,” I said.

They wouldn’t do it. That should give some indication of the disparity in the two contracts.

All this put a pall on what should have been the happiest time of my life. I kept on trusting something would work out, while laboring at bringing together again the things needed to make our series.

Rosenbloom and I attended a meeting in the CBS conference room with Shephard, Levin, Shephard’s lieutenant, Kim LeMasters, and Levin’s second in command, Bill Klein.

It was sort of an official start to negotiations, and it was here we would learn the parameters of what we needed to know to begin the real work of putting everything together again.

What was actually going on was celebratory. Something rare had happened, and we were the participants. It wasn’t a question of who won and who lost; maybe we all won. It was just that it was kind of an historical moment, which had everyone smiling and enjoying the afterglow.

Then LeMasters spoke up: “Since the show obviously failed in its last incarnation, what changes do you anticipate making in these next seven episodes to fix the series?”

Talk about your wet blanket. I said something about us being invited to come back and that I was not aware any fixes would be required. Shephard stifled his lieutenant, and we got on with the business at hand.

That meeting took place on September 28: three days after the

Emmys

, one week after the CBS capitulation. Up to this point, the women and their representatives had been relatively patient, awaiting Orion’s response to their opening salvo.

I had urged Rosenbloom to have open negotiations with the talent (Sharon, Tyne, and their representatives) and to rent a large table for the event (treating it all like the IA-AMPTP contract talks

36

), but I did not insist or fight for this idea hard enough. If I had been adamant, it probably would have happened; Rosenbloom rarely turned me down when I got that forceful. I was not adamant.

Rosenbloom’s plan was to prepare carefully, to negotiate first with the CBS network, and then, empowered by the network to do so, he would negotiate individually with Tyne and Sharon, treating them as equally as possible. This plan was supported by Rosenbloom’s management completely. I was the lone dissenter.

I felt the women needed to voice their frustrations to people in power. I felt they wanted—and needed—their day in court. I felt there were certain items (mostly billing) that could only be worked out between the women in a face-to-face situation. I also worried that the time consumed by Rosenbloom’s plan would only feed the women’s anxieties and lead us closer to Tyne’s departure date for the film she had committed to do in Europe:

The Aviator

, produced, as luck would have it, by none other than Mace Neufeld, which, despite the title similarity, was not the movie made famous by Martin Scorsese and Leonardo DiCaprio.

Three weeks passed; three agonizing weeks in which Sharon’s and Tyne’s ambivalence, paranoia, and fantasies flourished. Tyne’s departure date for Yugoslavia and her role in the Neufeld film drew near.

Three weeks. Rosenbloom finally called me to tell me the offer: “$50,000 per episode, per woman. Double their previous salary. What,” he asked proudly, “do you think of that?”

“It’s only money,” I countered. I did not think it would solve the problem.

Rosenbloom and I argued over this for a time, but it was now his ball, and he was playing this his way.

Why not, I asked, offer Tyne $35,000 per episode (a savings of $15,000 per episode) plus—through Orion—a $250,000 development fund for her and Georg’s company? It would be cheaper in the long run, and Orion might benefit from the association with Tyne and her husband. What about offering Sharon less cash per episode and deal with her primary fantasy of a beach house? I quickly invented a free rental and ultimate (after 100 episodes) free deed to Ms. Gless for this. Why not, in other words, find out what these people believed might make them feel good about the perpetual come to me/go from me commitment they were about to make and deal with what they really wanted?

Rosenbloom did not want to be bothered. He did not believe they could turn down this kind of money, and indeed he was right; they did not turn it down. In fact, the Orion economic package was immediately gobbled up. But, to Rosenbloom’s dismay, negotiations were far from over.

“Now,” said the two agents, “let’s talk about our other needs.”

Rosenbloom had operated from his own sensibilities and those of his management. He had shot his bolt in the first round. I had lived with these gals for months—for twelve to fourteen hours a day—I knew better. I should have been more adamant.