B004YENES8 EBOK (34 page)

Authors: Barney Rosenzweig

I was feeling on the edge. The bad news was constant and dribbled in from all sides.

My communication skills seemed to be failing me as one employee after another screwed up one assignment after the other. It would have been laughable were it not having such an awful cumulative effect on everything I was doing and, as a consequence, on me. The Howard Strickling phrase, “a fish stinks from the head,” continued to resonate.

Ronald continued to publicly flail about, blaming our production team, me, the directors, Carl, ABC—you name it. I imagine, in private, he even blamed himself. Everyone was crumbling, beginning to seek out targets to blame. Everyone, save for Carl Weathers. He seemed to not see problems, only opportunities. Mr. Weathers, at least in public, kept his game face on. One had to admire him.

Chapter 39

LET THE GOOD TIMES ROLL!

“Bigamist,” Tyne Daly was screaming at me from the toilet in Sharon’s motor home. Sharon, more than a little drunk, was trying to comfort me over the collapse of

Fortune Dane

.

Tyne, every bit as inebriated as her partner, yelled out the “bigamist” line again. I had gotten what I deserved, she bellowed. “Your place is with us!”

They went on about how it was important that my services be exclusively theirs.

Now

they needed me. Five minutes before they were turning shit into Shinola with help from no one. The conversation would bounce all over the place.

“If you’re saying you’re better than the material,” I countered, “no one will argue. You are the best at what you do on the planet. Everyone knows it, but it is very unnecessary to say so yourselves, and not particularly attractive to do so.”

We were at the beginning of what would prove to be our penultimate season; Estrin and List were now leading the writing staff. The material was not great, but certainly up to the norm for that time in a season. Tyne and Sharon were very critical, despite protestations that they “liked the new team as people.” Sharon began building a real jack story about the “unplayability” of the scenes, and both had forgotten (or didn’t care) that they had always felt this way about the scripts— whether authored by April Smith, Terry Fisher, Peter Lefcourt, or Liz Coe . Now they longed for those “great” writers from our past—and if it weren’t so sorely felt by them it would have been funny.

The women were bridling about the responsibility of having to go over and over the scenes before they would become “playable.” I strongly urged them to act. “Say the words, and don’t bump into the furniture,” I would add, paraphrasing the late, great Spencer Tracy. “Try just serving the material and don’t take on the job or responsibility of the entire entity. Let me do my job, and I’ll have the writers do theirs.”

Tyne and Sharon agreed to try. I remained sober throughout that three-hour session, taking the women’s abuse for a time, trying to insert an idea here or there, but mostly (and this was the best part) just watching them. The friendship, the guarded compliments or criticism, the occasional touched bruise, the recounting of (for what, the thousandth time?) their history together and how it came to be; the genuine affection, the lack of total honesty (out of fear of where that might take them), the miscommunications (as first one, then the other, missed a compliment or a moment of tenderness—and too bad because the moment was gone fast) it was my privilege to witness it all.

I remember considering staying sober at those sessions more often. The disadvantage to that was one felt not quite as included. I also recall considering taping those meetings of the troika but dismissing the idea as impractical.

We would finally part, hugging all around; no one wanted to be the first to leave (possibly out of fear of what might be said behind the back that wasn’t there). It was another rare evening with the ladies, one of many in my memory.

It was June 1986. Sharon, Tyne, and I were obviously on speaking terms again, but it did not come easily. The silent treatment I received as a result of the previous summer’s

TV Guide

article lasted several weeks, with Sharon finally breaking the hush by asking for a meeting in which she told me she wanted the dispute to end but that she needed an apology from me. When I asked why she would believe the apology when she did not give credence to anything else I had to say on this matter, Ms. Gless simply replied, “Because I want to.” I capitulated.

Months earlier, Steve Brown somehow, and very prematurely, learned of my plans to do

Dane

. He wasted no time in giving me his ultimatum that he would quit if I turned

Cagney & Lacey

over to Liz Coe . He managed to stir up a little hysteria at the time; first Rosenbloom called in a panic, then Gless (another nail in the Steve Brown coffin).

“You are who I act for,” Sharon had said. The good news was that this led to the subsequent talk of apology over the

TV Guide

thing. I assured both her and Rosenbloom that I was not leaving the series but merely pulling back a bit. Steve Brown was to depart with my blessings. Liz Coe would now lead the staff of Georgia Jeffries, Pat Green, and Kathy Ford. All this took a backseat to the arrival of fall and the festivities of the Academy of Television Arts and Sciences.

In 1985 (for the 1984–85 season), I received the first of my two

Emmy

statuettes as executive producer of the year’s Best Dramatic Series. I had been nominated twice before for

Cagney & Lacey

; in 1983, for the 1982–83 season, and 1984, for work in that shortened seven-show order year. This third time was definitely the charm. I won again in 1986 (for the 1985–86 season) and was then nominated for the fifth time in a row in 1987 (for the 1986–87 season).

66

I personally thought we would win in 1984 for that season of the seven-show order, not just because the episodes were among our best but because of the stir we had created by being canceled and then brought back. Steven Bochco’s

Hill Street Blues

was just too formidable, and I began to believe that if we couldn’t win then—with all that industry sentiment on our side—then we might just never prevail. I resolved to stop preparing speeches, and not because I’m superstitious (I am), but because all that rehearsing only added to the disappointment of losing. I remember being in that auditorium when the announcement came:

“And the winner is—

Cagney & Lacey

!”

I remember it, not only because it was an important event—a biography name changing event (instead of Barney Rosenzweig or Producer Barney Rosenzweig, I became for all time—at least in the trade press—

Emmy

Award–winner Barney Rosenzweig ), but I remember it because of something I felt midst that throng. There was something I felt, and there was something else that was absent.

For the first time in all my years of attending these occasions, I felt consensus, without a trace of envy from my peers. What was absent was the sound of the gnashing of teeth. I strode down that aisle to collect my reward, and the feeling I had from every one of those people applauding was:

“That guy worked hard for this,” or, “you can’t begrudge anyone who pulled off what he did” or maybe—just maybe—a sense that there could be justice in Hollywood .

Corny? It was my moment. My stroll down that aisle, and that’s how I remember it. I was one happy guy!

Weeks after that first win, our 1985 opening night garnered a rave review from

The New York Times

. We got a 34 share and easily took the hour. Harvey Shephard was delighted and called me with the good news. That same fall, Tyne had her baby and Sid Clute finally succumbed to cancer.

The

Emmy

excitement had not worn off. Mail congratulating me continued to pour in, and it was all very gratifying. People stopped me in elevators and on the street, recognizing me from the award show on TV, and congratulating me. Celebrity was something I was enjoying.

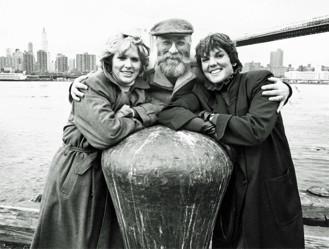

The view from Brooklyn. On location in New York, Sharon and Tyne give me arms full of talent in one of my favorite photos.

Photo: Rosenzweig Personal Collection

Our annual New York shoot for

Cagney & Lacey

was upon us, and I was looking forward to that—ten days in the Big Apple with Sharon and Tyne. I had to laugh as I found myself viewing this as an escape from Ronald Cohen and Carl Weathers. My female stars would, I was sure, present me with plenty of

mishigas

67

on their own.

The week in New York was excellent. It was true quality time with the women, plus some good footage shot, culminating with the storied Stage Deli asking the women to create a

Cagney & Lacey

sandwich. The two women had now entered the realm of such legends of the past fifty years as Joe DiMaggio and Frank Sinatra. (Typically, Sharon and Tyne, without regard for things commercial, created some awful combination that could not possibly remain on any menu for long.)

Tyne and I then went on to Washington DC as part of the promotion on our abortion show: Eight solid hours of public speaking and meetings. Ms. Daly was tired but in her element. I attended the National Conference of Working Women luncheon in DC, where the show was to be among several honored. A full house of nearly a thousand heard speeches and saw a tape montage of the year’s award winners and runners-up. The format then called for each of the recipients to stand at the appointed time at their respective tables, introduce themselves and their project, and say a word or two. This went on for some time to a polite, if unenthusiastic, audience. Finally it was my turn.

“Hello,” I began. “I’m Barney Rosenzweig, executive producer of

Cagney & Lacey

.”

The room erupted into applause. I was standing there a long time drinking it in. This was nice. This was better than smelling the flowers.

Back in L.A., I lunched with Peter Lefcourt. He was tempted to return to

Cagney & Lacey

and would let me know the following week. My day continued, ending at Lacy Street around 2 am, another in a series of late nighters. In Sharon’s dressing room around midnight, I remember attempting to explain why, as a director, Ray Danton was unique.

I pointed out, as I have so often before, that “he has no life, no friends. He just lives for the work.” The irony of making that fairly disparaging statement about someone else near the end of my own seventeen-hour day did not escape either Ms. Gless or me.

Liz Coe was getting closer to becoming a memory on

Cagney & Lacey

, as she was less and less able to inspire anyone’s confidence, except mine, and that was no longer good enough. Lefcourt would finally decide against a return, so my courtship of the writing team of Jonathan Estrin & Shelley List thus went into full gear with positive results; Liz would elect to leave the series, rather than “serve” under the new team. After our read-through of the season’s penultimate

Cagney & Lacey

script, I took Dan Shor aside and let him know his character (Jonah Newman) would be killed in that season’s final Chapter. He said he understood.

I had a nice half hour on the set with Sharon. She had just turned down a million-dollar offer to star in the twelve-hour miniseries Amerika, despite her feeling that it was the best script she had ever read. The problem was that it could not be done during the

Cagney & Lacey

hiatus. It was clear that the gossip of her trying to hold up Orion by not returning to the series was overstated. She pointedly expected me to return full-time next season, and I was able to hedge an answer long enough to allow her to be called back to the set. It is what I wanted to do, but I was not sure it was possible.

Could I simply stop the deal with Columbia? Tell them to keep their $800,000 per year? Could I ask them to suspend and extend? Would ABC roll over the six-show commitment to me for another year? I doubted it. Should I return to

Cagney & Lacey

because I love it, playing the fool to Orion and Mace Neufeld once more? To hell with them, you say. “Do what you want.” But how would I react months later, having possibly given up all the above? How would I react to one of those “lovers’ quarrels” between Tyne and/or Sharon and myself? I needed to make some very hard decisions.

Late one evening in February of 1986, even as

Fortune Dane

was winding down, John Karlen, Al Waxman, Marty Kove, Harvey Atkin, Carole Smith, Sharon, and I all gathered in my Lacy Street office after the day’s work. It was a minor laugh riot. Sharon called later to say that we had to make it a weekly event. It was great to feel my head on the pillow at day’s end and to think how much I enjoyed the respite from

Fortune Dane

and the evening’s interval with the folks from

Cagney & Lacey

. Then—at 12:40 am—the phone. It was Tyne Daly. She had just read Liz Coe’s “Parting Shots” script, and hated it. She couldn’t sleep after finishing it and didn’t want me to either.