B004YENES8 EBOK (43 page)

Authors: Barney Rosenzweig

January 7, 1996

:

The move from Malibu to Miami’s Fisher Island goes on. We are on, or slightly ahead, of schedule. On Friday last (1-5-96), Tom Nunan passed on my inquiry regarding NBC ’s level of interest, if any, in

MAGUIRE FOR HIRE

, or

MCQUE

(the Nancy Drew projects for Sharon). The rejection from this friend who thinks of me as a mini-father figure could not have been—all things considered—an easier let down. It still hurt. More than I could have imagined it would. I am no longer suited for this. If I had any doubts (which I don’t really think I did) today’s phone call could only reinforce the decision to get away from these people who give me too little and who hurt me too much.

January 8, 1996

:

At 12 noon, Steve Werner calls from CBS with the news that our air date will be January 29. A Monday, and against the

Country Music Awards

special, which is always a monster hit. I made no comment about Leslie Moonves and his promise of at least six-weeks notice instead of the three we were getting. Curiously, I am not in much of a fighting mode. It isn’t as it used to be—my “David” to their “Goliath.” I just feel as if I’ve passed all this. I am, let’s face it,too old now to play “David.” Tomorrow I will take most of the day off from packing to think on this and to, hopefully, come up with a plan. Right now it (the plan) is to do some campaigning, but to spend very little money on this and to deal with the show as if it were the last (probably is) and to go out with the dignity I think we deserve. Since CBS isn’t giving it to us, then I will.

I wrote a short press release. I was careful in the story not to be too overt, only obliquely referring to the lack of synergism between my own goals and those of the network. I massaged the story carefully so as not to sound like a victim and, in fact, did not feel like one. I phoned the Moonves office, saying to his secretary, “Tell him it is not what he thinks,” and “I believe he will be pleasantly surprised.” A few minutes later Moonves returned the call.

I told him that, contrary to what he might have guessed, I actually thought that returning

Cagney & Lacey

to a Monday night against the

Country Music Awards

was an interesting idea and possibly a great counter-programming move. The only problem was the short time-frame. He immediately broke in, wanting to apologize about breaking his word.

I interrupted. “Not important,” I said. “With this short a period of time, and with Gless in England, there is a distinct limit as to what I can accomplish with publicity,” I told him. “Without Gless and Daly to play off each other on the road, the only way I can get in the paper, to be the lead item in Liz Smith, or wherever, is to do and say things that are confrontational and somewhat controversial.” I added that I could appreciate the fact that he didn’t seem to like that.

“No,” he confessed he didn’t, but he wanted me to be out there plugging. He just “didn’t want to be mentioned or have CBS criticized in anyway.”

“Can’t be done,” I said. “I only know one campaign for this show, and it is always guaranteed to work. It’s the gal show against the all-male establishment that runs the network. It is David versus Goliath. That’s all I did last time, and it is all I’ve ever done. This time, it would just be me, so, although fundamentally it would be the same thing, I don’t have the star power of the women, so it would have to be a bit rougher to find its way into print.”

I didn’t want to do that, I said, and here was my solution: “We can’t do it with publicity, unless it is the very kind of publicity that you (Moonves) hate, so let’s do it with advertising, which you control!”

I went on to say I thought we could win, that I thought it was fate that he chose January 29 to air the show, because that’s the day I leave for Miami and I’m happy to have this be a going-away present from CBS .

The best campaign, I told him, would be for CBS to call it the last

Cagney & Lacey

ever—unfortunately, they couldn’t do that without risking a lawsuit for damaging the franchise. But, I added, “I could put out a press release:

‘

Cagney & Lacey Cancels CBS.

’

The press will eat it up with a spoon.”

I pushed forward. “It will in no way mention you, Les, or in any way bad-mouth the network. We are just going our separate ways.”

Moonves liked the idea, saying he would get right into it with his promo people but couldn’t promise a specific number of on-air promos.

91

I interrupted. “Promises don’t mean much to me anyway, Les,” I said with hardly an edge. “All I care about right now is that the final Chapter in this quartet of films I have made is treated with the respect my work, and the work of my stars, deserves.”

He agreed. He told me that none of this was personal; he wanted to assure me of that. I told him I couldn’t give less of a shit if it were. Just “Do all that can be done for this show, and we might scare the hell out of those music awards.” He thanked me several times for my attitude and for the ideas and said he’d get right on them.

January 12, 1996

:

My press release, cancelling the CBS network, went out today. I will be surprised if the press doesn’t have fun with this. Joan Carry, knowing that the TV press are all in town at the same hotel on a TV junket, had the release slipped under the door of each of their rooms this afternoon. I’ll keep my fingers crossed that this doesn’t backfire. I don’t think it will, though it is possible that if it generates heat on Moonves he will forget that he is part of this plot and will turn on me again. It’s worth the shot.

Moonves did turn. The story broke in the Morning Report section of the

L.A. Times

’ Calendar section under the headline, “Take That, CBS.” They printed a good portion of the story and got a quote from Moonves that I had “demanded” a commitment of ten

Cagney & Lacey

movies and that he would not make such a commitment. He would say no more, effectively letting the air out of our mutual publicity balloon. We managed to get good space in

The

Milwaukee Journal

and the

New York Daily News

, but that was pretty much it. The way these things work is to have fun with it, to keep this sort of thing going between the two parties. But Moonves trumped me at my own game by simply refusing to enter the fray; so much for synergy. “

Everybody

,” I noted in my diary, “

has an asshole. Leslie Moonves is mine

.”

92

By months end, our ratings on

C&L IV

would be published, and they were unacceptable. A 15 share—our lowest ever. I had stayed an extra day in L.A. in the hope that the ratings would be good enough to allow for some gloating time. No such luck; barely third in a four-horse race.

January 31, 1996

:

I will limp out of town this morning and look forward to a better life in Florida. Our Planet Hollywood party and screening just for us (no press) was great fun. Tyne cried a bit. John Karlen was quite pleased with the film, as were the fans that bothered to call and most of the reviewers who went to print. It was a good little movie. Whatever, I’m out of here.

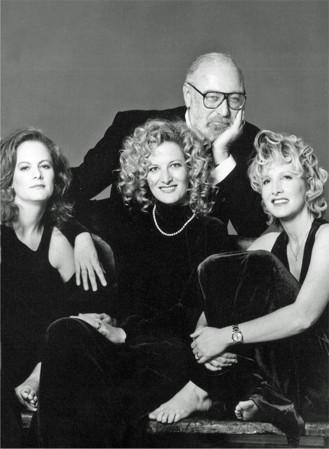

My best productions: from left,

Menopause Years

associate producer and award-winning filmmaker in her own right, youngest daughter,Torrie Rosenzweig; eldest daughter, Erika, who was featured in a small part in one of our reunion films and is married to David Handman, one of my favorite film editors; and Allyn, who worked as a costumer on the original series out of Lacy Street before becoming a full-time mom. The photo by famed photographer Greg Gorman was a gift from Sharon for my sixtieth birthday. The gift of my beautiful children was courtesy of first wife, JoAnne Benickes.

Photo: Rosenzweig Personal Collection

Chapter 47

MIAMI NICE

I had happily set up housekeeping at our new digs on Miami’s Fisher Island, commuting that first year between Florida and London to visit Sharon (who had, while costarring with Tom Conti in Neil Simon’s

Chapter Two

, justifiably become the darling of the English critics). My wife then went on to a five-year stint as Debbie, the PFLAG Mom, on Showtime’s groundbreaking series

Queer as Folk

, while Tyne Daly parlayed her

Tony

Award-winning performance in

Gypsy

into a long-term

Emmy

winning role on the CBS series

Judging Amy

. With a few brief interruptions, I have been enjoying life in general without work and with no dark clouds on my horizon.

No dark clouds. This is largely because my horizon is now seen from a small island off the coast of Miami Beach—as far as one can get from Hollywood and the film industry while still residing in the continental United States.

The industry in which I grew up has, coincidental with my departure, been in the throes of apocalyptic events. Besides the sometimes in and sometimes out of the business, MGM, what was Columbia Pictures Corporation, Tri-Star, and Embassy are now divisions or offshoots of the Sony Corporation. RCA Victor is no more; the image of the happy canine looking into his master’s gramophone is now nothing but a collector’s item.

The studios conceived by the Warner Brothers and Lorimar (a one-time giant of the television industry) are now merged with the Time Publishing Empire (HBO) and, for a while, Ted Turner. Rupert Murdoch owns both the Fox Studios and the Fox network and enough television outlets and newspapers and satellites to be scary. Universal Studios, NBC, and Telemundo are a division of General Electric, and Disney has taken over ABC and ESPN and more. CBS, the Tiffany network of William Paley, is now merely a division of Viacom, which also owns Paramount Pictures Corporation, to be cut loose or brought back into the fold seemingly at Sumner Redstone’s whim, or (I presume) in order to vie for more corporate shelf space.

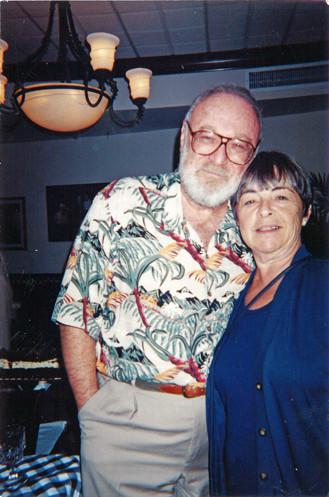

My fabulous longtime assistant, Carole R. Smith, at Miami’s famous Joe’s Stone Crab, to help me celebrate my sixtieth birthday.

Photo: Rosenzweig Personal Collection

Three in a million: 2004 with Carole King, Sharon, and me at the March for Women’s Lives in Washington DC, where I made the crack about all those women and not one of them remembering to raise the lid on the toilet seat.

Photo: Rosenzweig Personal Collection

We are at the time Brandon Tartikoff predicted in the 1990s of only a half dozen sequoias standing in the Hollywood forest—and not all of these are of domestic national origin.

93

In some ways we are only at the beginning of this cycle. If what has just passed has been the American century, then it is in no small way thanks to the entertainment industry. It wasn’t so many decades ago that French, the language of diplomacy, was considered the international means of communication; today, it is English. That is not thanks to Margaret Thatcher or any American politician. Teenagers in the Soviet Union who wear Levis and know the lyrics to Bruce Springsteen songs are responding to what they see and hear in the media, and most of that from the entertainment capital of the world.

Since the advent of World War I—and the subsequent need in Europe to use nitrate for gunpowder rather than motion picture film stock—that capital has been in my old hometown.

America may no longer make the best automobiles, steel, or even computers, but it still manufactures the best filmed entertainment in the world. That’s not a birthright; only Europe’s past mistakes made it possible in the first place. Now it is the United States that is making the mistake of underestimating the value of the export of the American Dream, and it is difficult to judge just where we will go from here.

Approaching my seventieth year on the planet, I confess to being less interested in what is to come than what has transpired. My past, the mistakes and the triumphs, the wins and all the other stuff, is my legacy. It is, I suppose, the hope of any purveyor of autobiographical material that their not-so-recent past will resonate for others besides themselves, and so, in conclusion, I submit what follows:

In the seven years between 1981 and 1988, I produced 127 hours of

Cagney & Lacey

. One hundred twenty-five hour-long episodes and a two-hour movie-for television—all broadcast on the CBS network—and all for a then-publicly held company known as Orion Pictures Corporation. Later, in 1990 and into 1992, I produced another television series,

The Trials of Rosie O’Neill

, also broadcast on CBS, but this time for The Rosenzweig Company. (The Rosenzweig Company production of the four

Cagney & Lacey

reunion films would come about in the mid-1990s.)

On the air for six years,

Cagney & Lacey

was an authentic hit, grandfathered under the Department of Internal Revenue’s then-existing and generous investment tax credit rules. It was produced (I mention yet again) at or near the network’s license fee. There seemed to be almost unlimited opportunities for profit: the distribution of the production itself (both foreign and domestic), the prospect of substantial merchandising and commercial tie-ins, plus the eventual marketing of various video packages. It was all in the realm of the possible for that series.

The Trials of Rosie O’Neill, although celebrated as the highest-rated, best reviewed new dramatic series of 1990, had only thirty-four hour-long episodes during its two-season run on CBS. In the time that had passed since Cagney & Lacey, Ronald Reagan had deregulated the television industry, with the resultant collapse of the syndication market for hour-long dramas; the investment tax credit had been rescinded by Congress; and, with only two seasons on the air,

Rosie O’Neill

had virtually no chance of any kind of merchandising or marketing tie-ins.

For a thirty-four episode series, there is little or no afterlife; certainly no syndication, no cable sale, no demand for videos. Despite all that, in those two years, I made nearly as much money as I had in the over seven years I had been involved with the two most renowned women law enforcers in the history of television. It was, for a brief time, almost a license to print money. It was the difference between being an owner (as I was on Rosie) and an employee, however well thought of, as I was on

Cagney & Lacey

.

The religion of the television producer has always preached one primary doctrine:

Make 125 episodes of anything—reasonably close to the license fee—and you may spend the rest of your days (should you so desire) floating aboard your own yacht on the Aegean.

I didn’t get the boat. The promised dollars weren’t there.

The TV producer’s religion, however, isn’t always about money. After all is said, done, and dealt with, regardless of the changes of rules by governments, the Lawsuits, the wrecked marriages, the greed, stupidity, and downright dishonesty by former partners and self-proclaimed allies, the perceived unfairness of the system—there is one undeniable truth:

Had God, all those years ago, visited my office, and said:

“Barney Rosenzweig, there will be a television series. It will be called Cagney & Lacey, and you will make that show. It will be canceled and you will save it … more than once, and everyone will know it was you who did so. The network will tell The New York Times and the world that it has made a mistake and that you, Barney, were right and they were wrong. Your peers will honor you. There will be

Emmys

,

Golden Globes

, and many other honors. You will be celebrated by your university, your community, and your industry. Women’s groups throughout the nation will name you their ‘man of the year.’ You and your show will be written of in virtually every television history book for the remainder of the millennium.

“But … there will be no money.”

I would have filled the briefest moment of silence following all of that with one simple question:

“God, where do I sign?”

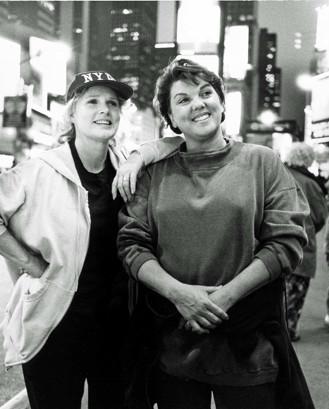

On the set (Times Square, New York City) for the finale of the first of our quartet of

Cagney & Lacey: The Menopause Years

reunion films.

© CBS Broadcasting Inc. John Seakwood/CBS