B006OAL1QM EBOK (33 page)

Authors: Heinrich Fraenkel,Roger Manvell

In the evening I had a long talk with my mother who, to me, always represents the voice of the people. She knows the sentiments of the people better than most experts who judge from the ivory tower of scientific inquiry, as in her case the voice of the people itself speaks. Again I learned a lot; especially that the rank and file are usually much more primitive than we imagine. Propaganda must therefore always be essentially simple and repetitive. In the long run basic results in influencing public opinion will be achieved only by the man who is able to reduce problems to the simplest terms and who has the courage to keep for ever repeating them in this simplified form, despite the objections of the intellectuals.

49

Goebbels entering the Tennishallen with his usual bodyguard of StormTroopers, April 1933.

The gestures of the Orator.

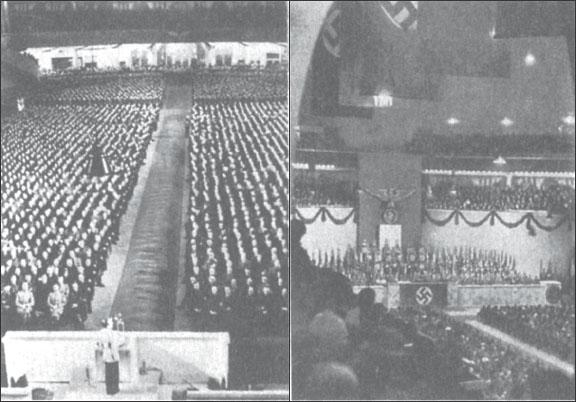

The Sportpalast:

left,

a Nazi rally seen from the platform end of the hall;

right,

the rostrum and banners.

This special form of radicalism left Goebbels free to declaim against any traditional form of power that he happened to dislike on the grounds that it was negative, reactionary and out to frustrate the New Order which National Socialism represented in Europe. Diplomats, lawyers, generals—all in turn came under his lash.

The weakness of diplomacy lies in its social ties. These can never be quite overcome, and one must therefore be conscious of this weakness when determining one's policies. One must not stick to old methods that have long been outmoded but must conduct politics and war with modern methods.

50

It really makes one despair to see how the bureaucracy of the civil service tries again and again to cramp the style of those who favour a radical conduct of the war and to create one difficulty after another for them. This bureaucracy always rests its case on so-called common sense and the wisdom of experience. Now the point is that our great successes in the past were achieved thanks to neither of these qualities. They were the result of clever psychology and a pronounced ability to sense the thinking processes of the broad masses of the population.

51

Goebbels was also much concerned about the place of the Church in the National Socialist State. He resented the hold religion had on the German people, but regarded the whole problem as one which could not be faced until after the war. The best thing, he felt, was not openly to antagonise the Churches at this stage. In fact he admitted to von Oven, his aide, as late as April 1944, that neither he nor Hitler had ever discontinued payment of the normal Church taxes, which, according to the custom, everyone had to pay to his acknowledged denomination. Goebbels appreciated the irony of the situation, since the bulk of his income came from books that contained statements against the Church. Nevertheless, he was angry, for example, when the Party removed crucifixes from schools and hospitals.

It can't be denied that certain of the Party's measures, especially the decree about crucifixes, have made it altogether too easy for the bishops to rant against the State. Göring, too, is very much put out about it. His whole attitude towards the Christian denominations is quite open and aboveboard. He sees through them, and has no intention whatever of taking them under his protection. On the other hand, he agrees with me completely that it won't do to get involved now, in war-time, in such a difficult and far-reaching problem. The Führer has expressed that viewpoint to Göring as he often has to me. In this connection the Führer declared that if his mother were still alive, she would undoubtedly be going to church today, and he could not and would not hinder her.

52

On the other hand, he resented an article published in Italy by Vito Mussolini, a nephew of the dictator, which stressed the need for Europe to retain the Christian leadership of the world. Goebbels' observations are significant:

It is obvious that the Italians are trying to lay claim to the spiritual leadership of Europe, since leadership in military affairs and in power-politics has slipped completely from their hands. I am ignoring this article in our commentary. There is no point in replying to such provocations now, as we are not yet in a position to publish all our arguments. We shall have to await a more favourable opportunity. We shall probably not be able to tackle the Church question bluntly until after the war.

53

Goebbels knew from personal experience the nature of the hold that both the Catholic and Protestant Churches had on large numbers of the German people. He was shrewd enough to realise that the inevitable trial of strength that must eventually take place between National Socialism and the religious conscience of millions of the German people had at all costs to be postponed until after the war was won and the greatness of the Nazis' own faith in themselves and their Leader vindicated before the world. Christianity in Goebbels' view was at one with the bourgeois values he detested because they were impervious to his propaganda and could only ultimately be answered by the extreme measures of the concentration camp to which recalcitrant priests had to be sent and where so many of them displayed a notable courage and great powers of resistance.

It is plain from the way this statement is worded that Goebbels realised the great problem the National Socialists would have to face when conflict with the Churches was finally brought into the open. He even doubts whether it is wise to bring to public trial a group of clergy who had been arrested for listening to broadcasts from Britain, and brought the matter to Hitler's personal notice so that the possible repercussions of the trial could be studied. It is even probable that religion still had some unconscious hold on Goebbels; this might account for his plan, outlined to Semmler, one day to write a book on Christianity.

His dislike of bourgeois values extended to sexual morality. In April 1942 he makes the following observations on his own district of Berlin:

Prostitution in Berlin is causing us trouble these days. During a raid we found that 15 per cent of all the women arrested had V.D. and most of these syphilis. We must certainly do something about it at once. In the long run we cannot possibly avoid setting up a “red-light district” in the Reich capital like those in Hamburg, Nuremberg, and other large cities. You simply cannot organise and administer a city of four millions in accordance with the conceptions of bourgeois morality.

54

Goebbels' observations on Germany's principal antagonists, Britain, the United States and Russia, are of considerable interest. The opinions expressed in his official, personal diary should represent his true feelings; but if they do, it is strange to find such an outlandish mixture of shrewdness and sheer ignorance in a man of his intelligence who had had access for about ten years to confidential reports from German agents and embassies. In fact, his lack of knowledge of foreign peoples was one of his great weaknesses.

Of the Russians he writes:

They are not a people but a conglomeration of animals. The greatest danger threatening us in the East is the stolid dullness of this mass. That applies both to the civilian population and to the soldiers. The soldiers won't surrender, as is the fashion in western Europe, when completely surrounded, but continue to fight until they are beaten to death. Bolshevism has merely accentuated this racial propensity of the Russian people. In other words, we are facing an adversary about whom we must be careful. The human mind cannot possibly imagine what it would be like if this opponent were to pour into western Europe like a flood.

55

He accepted the veracity of reports from the occupied territories in the East that starving Russians were prepared to eat human flesh, but was, however, a supporter of a policy which attempted to win the support of those Russians who were antagonistic to the Communist régime by setting up some semblance of free institutions under the German rule. In a thoroughly Machiavellian passage in his diary for 22nd May 1942 he writes:

We could reduce danger from the Partisans considerably if we succeeded in at least winning some of these people's confidence. A clear peasant and Church policy would work wonders in this respect. It might also be useful to set up sham governments in the various sectors which would then have to he responsible for unpleasant and unpopular measures. Undoubtedly it would be easy to set such governments up and we would then have a facade behind which to camouflage our policies. I shall talk to the Führer about this problem in the near future. I consider it one of the most vital in the present situation in the East.

56

His views on America are equally devastating:

A report on the interrogations of American prisoners is really gruesome. These American soldiers are human material which can in no way stand comparison with our own people. One has the impression one is dealing with a herd of savages. The Americans are coming to Europe with a spiritual emptiness that really makes you shake your head. They are uneducated and know nothing. For instance, they ask whether Bavaria belongs to Germany and similar things. One can imagine what would happen to Europe if this dilettantism were to spread unchallenged. But we, as it happens, shall have something to say about that!

57

I have received statistics about the number of Jews in the American radio, film and press industries. The percentage is truly terrifying. Jews are 100 per cent in control of films, and 90 to 95 per cent of the press and radio.

58

About the British he is scarcely more complimentary, though he has during this period a great deal more to say about them:

One really wonders on what grounds the English had the insolence to declare war on the Axis powers. Either they did not know our superiority and their inferiority, or else—and this seems more plausible —they intended from the very beginning to have other countries and peoples do their fighting for them. At any rate, that's where I attack the English vigorously in the German press and also in our foreign-language broadcasts.

59