B006OAL1QM EBOK (37 page)

Authors: Heinrich Fraenkel,Roger Manvell

Goebbels' social and domestic life.

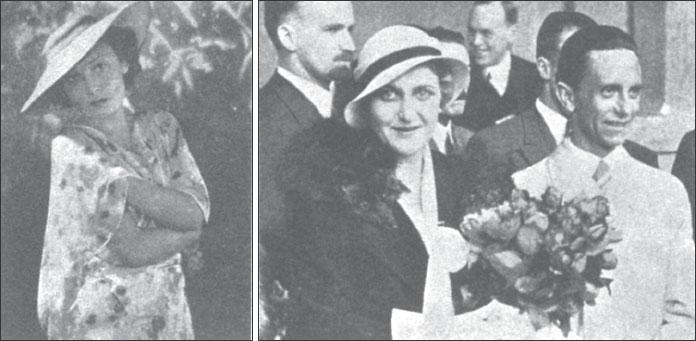

Above, left,

at the theatre with Prince August Wilhelm and Princess Bathilde of Schaumburg-Lippe ;

right,

at the marriage of his sister Maria to Max Kimmich in 1938.

Below,

at the helm of his motorboat on the Wannsee.

Lida Baarova at the time of her association with Goebbels

(left). Right,

with Magda and Hanke (bearded).

The Family group, 1942.

After dinner the Minister and those present for the meal would very often see a programme of films which might, if the date were appropriate, include a preview of the current newsreel prior to its public release. Goebbels invariably became excited by films. He saw everything on which his agents could lay their hands. The Press attaches in the German embassies in Sweden, Switzerland and Portugal were under orders to get hold of prints of American films and have them illicitly copied for him. One evening in the summer of 1943

Mrs. Miniver

was screened at Goebbels' house. He was enraptured by it, according to von Oven. “What wonderful propaganda for the Allied cause!” he exclaimed. “What a wave of sympathy for the British and hatred for the Germans comes out of this film! Surely this isn't merely a work of art; it is also excellent propaganda.” A few nights later they saw a new German film, which Goebbels disliked intensely. “What idiots!” he shouted. “We Germans seem to be people without any subtlety at all. We just don't know anything about intimate effects. Can't they do anything but shout? It's enough to drive you to despair!”

Goebbels would talk on till midnight, using those with him as a sounding board for his monologues. Then he would shake everyone by the hand. Often he would take books and gramophone records up to bed with him in case he could not sleep.

During the intense bombing-raids on Berlin, Goebbels remained very cool. He exasperated his valet, Emil, because of the inordinate time he would take to dress before descending to the air-raid shelter, which was luxurious and fully equipped as an office—it had been built at a cost estimated at 350,000 marks in March 1943. He prepared himself for this enforced public appearance just as meticulously as he dressed each morning. In any case, he was always ready during the raids to drive to the Central Air-Raid Post in order to receive the latest news and supervise the work of fire-fighting and rescue. The Minister was, after all, also Gauleiter of Berlin.

38

When Goebbels travelled, as he frequently did either to speak in one of the main cities, to visit the badly bombed areas or confer with Hitler at his military headquarters, he would go either by car or train. He would work in his office up to the last minute, the staffcars standing ready. The journey to the Anhalter Bahnhof took three minutes exactly; the Minister entered the Mercedes, therefore, five minutes before any train he was taking was due to depart. Together with his staff he would march along the platform towards his special Pullman coach, which had been attached to the train. With a minute to spare he was on board, acknowledging in transit the Hitler salutes with which the station officials stood ready to greet him. The moment he had taken his place on the train, official work was resumed where it had been left off. Ochs, his Ministry batman, was there in charge of his luggage; Otte, his chief secretary, supervised his dictation. The Pullman had sleeping accommodation and a kitchenette, and the main compartment was well appointed in mahogany, with standard lamps dispersed over the carpeted floors. On arrival at any main station the coach would be connected instantly with the local Post Office telephone network. Von Oven remembers one such journey as this to Dresden, where Goebbels was due to meet his wife at the station because she was in the city taking a cure at a sanatorium. While Goebbels was greeting his wife and presenting her with a bunch of roses accompanied by a kiss on her mouth, the Post Office officials were busily engaged connecting up the Pullman telephones. Magda had dressed all in white in readiness for this public presentation of white roses from her loving husband.

1943 was a year of disappointment for Goebbels in his political ambitions, as we have seen from the evidence of his diary. This is confirmed throughout by Semmler's independent testimony, On 4th January at a conference of the Ministry's departmental heads he lectured them on the need for a total mobilisation of the nation's resources and manpower in order to prevent Germany losing the war, particularly on the Eastern front. Germany, he said, was still not making her maximum effort. Two weeks later he received a bitter blow when Hitler appointed a Committee of Three consisting of Lammers, Bormann and Keitel to carry out what Goebbels claimed were his own plans to put Germany on a total war basis. Goebbels found himself relegated to the position of adviser only to this executive group, every member of which he despised and disliked; their debates, he said at home, were like a Punch-and-Judy show on the very eve of the fall of Stalingrad.

39

Goebbels' only answer to this was to issue a total war challenge of his own in a great speech—one of the outstanding pieces of oratory in his career—that he made on 13th February in the Sportpalast. With Stalingrad fresh in his heart, Hitler had refused to speak. Goebbels decided to use a new technique of shouting challenging and rhetorical questions at his vast audience in order to rouse them to roar back at him the replies he needed to show Hitler their determination to wage a total war.

He prepared the speech in a state of nervous anxiety, working with his secretaries on draft after draft until four o'clock in the morning of 13th February. The speech was designed to work the audience of twenty thousand into such a state of mass enthusiasm that when the time came to put the questions there could be no answer but

“Jal”

from the mass of faces below him. Goebbels rehearsed every phrase, every significant gesture. He used a mirror for these rehearsals. Once before his audience his self-assurance was complete; he marked this speech by a new style in his delivery, abandoning his usual elegance for a grim urgency of utterance. He built up the threat of Bolshevism. He made it plain that Germany alone could save the civilisation of the world. Illusion was a thing of the past. “Total war is the command of the hour.” Gradually he worked his audience up until their shouting became a feature of the performance. Then, and only then, he reached the point of challenge. He asked them, as representing the whole of Germany, to give their answers, yes or no, whether they were ready to make the great sacrifices necessary to bring about a lasting victory. Any eyewitness to the effect of this challenge on the audience described the result as a turmoil of enthusiasm, and the shouting rose like a hurricane. Taking his time, Goebbels expounded his ten questions, and demanded an unflinching

“Ja”

or

“Nein”

from his audience. He challenged them to affirm their belief in the Führer and in victory, their desire to continue the war with “wild determination” and to work when necessary sixteen hours a day to supply the means to defeat Bolshevism. Then he demanded their approval that women should give their whole strength to the war and that death should be the penalty for shirkers and racketeers. The whole German people must declare their willingness to shoulder equally the burdens of war. As question followed question from the booming loud-speakers the concourse resounded with the echoing roars of

“Ja!”

After his triumph Goebbels was carried shoulder-high from the hall. He weighed himself that night, as he always did after any major exertion in public speaking, and he claimed that he had lost seven pounds.

40

But all this effort availed him nothing. Hitler did not give him the control of the measures for total war that he coveted.

And so he turned to the substitute for power, publicity. He prepared the public to accept him as a leader, if Hitler would not. He worked hard at his articles for

Das Reich

and at his broadcasts, and he saw to it that his name was prominent in the daily news. He spoke frequently at public meetings in Berlin and elsewhere, taking full advantage of the silence of the other Nazi leaders. He also, as we have seen, popularised himself by his frequent visits to badly bombed areas, as Semmler describes:

Yesterday I was in Cologne with Goebbels. I saw a heavily bombed city for the first time. Goebbels was very shaken and wants Hitler to visit the city as soon as possible. It is surprising that Goebbels was everywhere cordially greeted in the streets. He talked to people in the Rhineland dialect. One sees even in Cologne that, at the moment, he is the most popular of the nation's leaders. These suffering men and women feel that at least one of them is interested in their fate.

41

His aim, according to Semmler, was to build himself up in the public esteem as the second man in Germany after Hitler. This substitute for real executive power would, he felt, stand him in very good stead when he eventually was able to persuade Hitler to give him the controls he sought.

Nevertheless, in one of those rare revealing moments in which Goebbels was prepared to face openly the truth about himself in front of others, he admitted to Semmler that this new popularity of his had been by no means inevitable and had had to be re-made from nothing.

Nothing, added Goebbels, is harder than to recapture lost popularity. He himself had learnt a bitter lesson. Only after four years of the most strenuous work had he won back some of the confidence and respect he had forfeited in 1938. Now he felt convinced that his star was in the ascendant again.

42

It was evident from the date that he must have been referring to the public scandal over his affair with Lida Baarova which had nearly cost him his career.

That he had not lost his amorous touch even in these adverse times is revealed by this charming story told by Semmler. It happened in June.