Babel No More (20 page)

Authors: Michael Erard

Boothe had offered to test Fazah, to which Fazah at first agreed, as long as he could make some money at it, but then they fell out of touch, and Fazah again disappeared.

From afar, the hyperpolyglot is a glowing example of the sort of human being who, in myth, all humans once were and whom we should all aspire to be again: someone who builds towers in hopes of encountering

the divine.

Then see this figure up close, as I did. See him sitting in his sunlit study. See his spreadsheets, his tapes, his books double-stacked on the shelves, and his living room empty, his refrigerator bare. Alexander may be a language god, a kind of archi-polyglot, but the truth about his life is far from the divine. His family was traumatized by their narrow escape from Lebanon. Alexander

taught for a few semesters at a small college shut down by the financial crisis of 2008, and he’d cashed in some long-term investments to pay daily expenses. When I met him, he was living on unemployment checks and Korean translation work.

As for me, I felt abandoned by him in the labyrinth of this topic, since he wouldn’t help me with Fazah and wouldn’t agree to a test of his language aptitude.

Then, after visiting him twice and transcribing hours of our interviews, we developed a jokey relationship, and I came to

consider him a holy man. Others do yoga; Alexander does grammatical exercises. He tracks his linguistic progress through the hours as saints once cataloged their physical self-sacrifices. And like a linguistic whirling dervish, he inspires by the excess of his ecstasy, a man

who doesn’t need schools or corporations but will make a place, a home, for hyperpolyglots. No wonder his YouTube channel has thousands of subscribers, and his online friends, many of them hyperpolyglot hopefuls, respect him and seek his pronouncements: they want to touch him, and thereby gain a piece for themselves of what he represents. I was not immune.

Alexander, the hyperpolyglot guru, asked

me, “What language do you want to work on? We could work on something while you’re here.” He radiated optimism that I could, in fact, do this.

“I’ve done Spanish and Mandarin before,” I said. “Hindi’s caught my eye, for some reason.”

“You can definitely do all of that,” he said.

I hadn’t told him about Russian yet.

A couple years back, I felt that my brain needed a certain type of exercise

I knew I could get from studying a language, which had to be a language I could read. Russian fit the bill, and I signed up for a class at the community college, excited to be there and to work hard. The teacher, a part-timer, wasn’t a native speaker. He was a short man in his sixties, probably someone who’d dropped out of a doctoral program and been hired for his Muscovite accent. I nicknamed him

Mr. Bombastic.

I’d floated into the class on a cloud of good feelings; I was doing my duty as a global citizen, broadening my mind, becoming more sensitive to foreign cultures. Quickly the experience soured; instead of Russian, I learned speechlessness. There we were in the early twenty-first century, reciting unlikely sentences from a book and pointing at pictures.

Is it an elephant? Yes, it is an elephant

. Sixty years have gone into researching foreign-language pedagogy and second-language acquisition, and none of it had touched Mr. Bombastic, who taught Russian grammatical rules like this: write a rule on the board, give a few examples, make students recite.

Voilà.

Then he’d move on to the next rule. He taught like a jaded stripper. In violation of other precepts, he piled reading

and

writing in Cyrillic print

and

cursive on top of grammar and vocabulary work, as if

this were a premed weed-out class. Even the girl who had lived in Moscow was crushed into silence. Good feelings evaporated.

Later, I would meet with Andrew Cohen, an applied linguist at the University of Minnesota, who also happens to be a hyperpolyglot—he’s studied thirteen languages as an adult and learned

four of them to a very high degree—and he sympathized. “We’re force-fed a lot of rules that are useless. Rules for certain kinds of articles we use in English. I know that Asian students have long lists with fifty-seven rules, and they memorize whether to use ‘the’ or ‘a.’ Native English speakers just know what it is. But why waste your time and energy on that?

“When I was studying Japanese,

we had a lesson on buying a tie in an elegant department store in Tokyo, and we had to memorize for the test the words for ‘subdued,’ ‘gaudy,’ ‘plaid,’ ‘polka dot,’ and ‘striped.’ In my mind I’m going, Why? When I buy a tie I never talk to anybody—I just go to the rack and take it. Why are they making me learn this stuff? There was another lesson on talking to my doctor about what kind of diarrhea

I had. I said, if I’m that sick, I’m going to an American doctor, or at least someone who speaks English. When I’m sick, it’s not time for a language lesson.” Talking to Cohen and other hyperpolyglots, I realized that, unlike me, they can learn no matter what the teacher’s method.

I lasted as long as I did being tortured by Mr. Bombastic because I adapted the class to my own needs—I stopped writing

homework in cursive, for instance, because I’m too old for penmanship. What would he do, fail me? I didn’t need a grade. It also helped that I sat in the back row with a sprite of a high school language nerd named Elizabeth who was taking the class for fun. When Bombastic insisted that we speak in complete sentences, “in good Russian,” as if Russians only speak in complete sentences, Elizabeth

muttered, “The rain in Spain falls mainly on the plain.”

I should have quit but didn’t. I wanted to be studying Russian. So I invented some games to make the best of it—which, I realize now, is what a prisoner does. It’s common sense that when you teach the words for family members, you ask students to bring in photos of their real families, to tap into one’s emotions as a pedagogical aid; I’ve

taught it myself that way, when I taught English in Taiwan. Because Bombastic

did not exert such effort, we sat pointing to imaginary photos.

This is my mother, she is a doctor. This is my father, he is an architect.

The best solution: outdo the absurdity.

“This is my mother,”

I said to Elizabeth, pointing at an imaginary photo, reciting aloud to the class.

“She is a woman who works on asphalt

.”

“So is mine!

” Elizabeth said.

“This is my father,”

I said. “

He is a veterinarian of elephants

.”

“So is mine!”

Elizabeth said.

Some classmates chuckled. Most were astonished. Bombastic let fly a smirk. “In the old Soviet Union, people had to meet certain production quotas. These two,” he said, “are like the guy who goes over the quota.”

Bombastic wasn’t happy with my customizations. One

evening, he gave us a practice exam that didn’t test what we’d been studying, and for me this was the final straw. Furious, I told him the exam wasn’t fair, and he accused me, incorrectly, of slacking off, as if I were a freshman punk. We almost came to blows in the front of the classroom. He scurried away, and I never went back. What I am left with is the confidence that if I should find myself in

Moscow, I will be able to correctly identify an elephant.

“What do you want to work on?” Alexander asked.

“Hindi,” I said.

Hindi it was.

At a nearby park, we met up with a lanky Berkeley undergrad named Justin, who had recently been exasperating Alexander, his tutor, by not shadowing as prescribed. So the polyglot sent him on a looped bit of path running down into the shade, then back up into

the sun, past young women sunning in the grass. Part of the advantage of shadowing in a park is that people are going to stare, so you get used to it. The problem is, Alexander joked, that in Northern California, to get people to stare, you have to be

really

strange.

After several circuits, Alexander ambled next to Justin, encouraging him to shout more “Italianly.” As the two men orbited by,

shouting and gesturing dramatically, as if they were declaiming opinions in the midst

of some vehement argument, I spoke to one sunbather, who had wandered down the hill.

“Does this look weird to you?” I asked.

“Kind of,” she said. “What’s going on? Is he learning Italian?”

“The guy on the right, he’s the teacher,” I explained.

“He’s good.”

“Do you speak Italian?”

“No, I speak Spanish, but

I’ve been to Italy. Where is he from in Italy?”

“He’s not Italian, he’s American,” I said. Her eyebrows went up. “Actually, he knows a lot of languages, he says, and he wants to start a school to make more people like him.”

“Oh, like a language cult,” she said, as if this were a commonly recognized phenomenon.

When Justin finished, Alexander offered the tape recorder to me. I’d chosen an Assimil

Hindi tape.

Le Hindi sans Peine,

the label read.

“You’ve just promised me Hindi without pain,” I said.

“I’ve promised you nothing like that,” he said.

I started walking, gesticulating, the stiff foam earpieces flapping on my ears and leaking warbly Hindi sounds into the afternoon air. I felt a few of the sounds going into my ears and come out my mouth. Then I felt a few more. Progress. No one

else in the park seemed to notice me, because half an hour of Justin and Alexander’s declamations had bored them. Stand up straight and talk louder, I told myself. This was hard. I couldn’t make out the long words in a phrase and had to stop speaking to listen.

Garam garam hai

. Oh. What does that mean? “Hai,” sounds like “hay,” over and over.

Garam garam. Mera naam

. Suddenly it sounds to me very

Sanskrit. I have a yoga teacher who opens class with a Sanskrit chant whose parts sound like

garam garam cai hai. Ji ha. Mera naam

. Is there some grammatical ending for asking questions, the

hai

?

*

At a certain point Alexander came to my side; in the valley of Hindi syntax, the polyglot saint walketh beside me, and I had no fear. Amazingly, he was speaking Hindi too. How? He said he has it “internalized.”

After three lessons on the tape, I stopped and apparently had done

so poorly that Justin critiqued me: stand up straighter, talk louder, he says. Shout! Alexander nodded approvingly. You looked worried, he said. Well, yes, because I couldn’t make out the words on the tape and I wanted to say, Forget it. We sat on picnic benches and went over the pages of dialogue in the textbook. Do you want to

do it again? Sure. This time, you have to be louder, faster, straighter. Yeah, yeah.

After shadowing three dialogues again, it happened: Hindi opened up. I’d never sought out methods or secrets; all I knew was what I knew about studying: you plug away, you memorize, you write out sentences, you practice endlessly. Flash cards. At first shadowing had seemed absurd. Yet the gates to Hindi were—I

could feel it—parting before me.

“You have promise, you definitely have promise,” Alexander says. “You know more than I thought you did. You surprised me.”

Sunshine, sunshine. Now give me someone from whom I can elicit words. Let me play board games with a little kid. Give me a hyperpolyglot, who will baptize me in his confident shadow, who has no inhibitions, even though he’s not a native speaker.

In the next year, Alexander’s life will change again, for the better this time, though only after, on the advice of a friend, he stopped describing himself on his résumé as a polyglot. He’s now a language specialist for the Southeast Asian Ministers of Education Organization in Singapore, a multilingual city that could be a polyglot’s playground, but he hasn’t had time to explore Malay or Tamil,

two of the official languages there; because he can’t get Beirut out of his head, his most active language pursuit is Arabic. He maintains his aspirations to open a polyglot school and is proud of his sons’ achievements in languages. When his eldest son wins a prize for his poetry, however, it’s in English, not Chinese or French.

I’ll always remember how, after the Hindi lesson in the park, we

went to a used-book store, where Alexander mooned over dusty tomes of German philology that he couldn’t afford. After we browsed the foreign-language section together, I headed to the natural history shelves, alone. Alexander popped up to ask, “You’re not telling me you have a well-rounded mind, are you?” Somehow, my performance in Hindi had lightened him to teasing. I shared his buoyancy; I’d been

complimented by a hyperpolyglot.

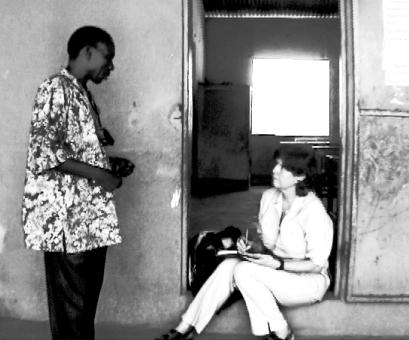

One sweltering afternoon in August, I went to World Bank headquarters in Washington, D.C., to meet another kind of hyperpolyglot, even more rare: a woman. At the front desk, the guard said there was someone frantically looking for me. As I stood there, the phone rang, and the guard, holding the receiver away from her ear, raised her eyebrows at the person shouting

on the other end.

That’s her,

she mouthed. A couple of moments later, Helen Abadzi, a tallish woman in a short skirt and a state of brisk disarray, swept into view.

Back in her office, quietly tucked behind her desk, she described how she flies all over the world evaluating the progress of educational programs, particularly in literacy, that have received World Bank funding. Born in a small town

in Greece in the 1950s, she said that one thing she wanted to be was weird, and that “one way to be weird in a town that once teemed with Sephardic Jews was to learn Hebrew.” So she took Hebrew classes at fifteen and was fluent at twenty-one—this linguistic knowledge she later applied to Arabic.