Babel No More (15 page)

Authors: Michael Erard

On the street and in the ether, Babel grew. Governments began to acknowledge that multilingualism was a major feature of the geopolitical future. In 2002, the European

Union advocated a “mother tongue plus two” educational policy.

*

In the last five to ten years, countries as diverse as Colombia, Mongolia, Chile, South Korea, and Taiwan have embarked on ambitious plans to make their countries bilingual—and English isn’t always the second language.

The hyperpolyglot embodies both of these poles: the linguistic wildness of our primordial past and the multilingualism

of the looming technotopia. That’s why stories circulate about this or that person who can speak an astounding number of languages—such people are holy freaks. Touch one, you touch his power. That’s why Mezzofanti was challenged to a tournament by Pope Gregory XVI, and why Russell and Watts argued about how many languages he knew. It’s why the governor of Massachusetts hailed Elihu Burritt,

and why Ken Hale became a myth despite his protests. Once you say you speak ten languages, you’ll soon hear the gossip that you speak twenty or forty. That’s why people who speak several languages have been mistrusted as spies; people wonder where their loyalties truly lie.

That’s why someone could want to be a polyglot.

I’ve gotten a bit ahead of my story, because at the point that Dick Hudson

and I were swapping names of deceased language superlearners, I was still looking for a living specimen. I learned about a Swedish language enthusiast, Erik Gunnemark, and mailed him the article I’d written about language superlearners. A few weeks later, his neatly typed reply (he didn’t use email or computers) arrived. He had been working

on his own book,

Polyglottery Today,

but his collaborators

had moved on, and now he was too frail to continue. A dedicated traveler, Gunnemark was no linguistic slouch himself, noting that he speaks six languages fluently, seven languages fairly well, and fifteen at a “mini level” (or for simple everyday conversation). He also said he could translate from a total of forty-seven languages, though for twenty of them he needed dictionaries.

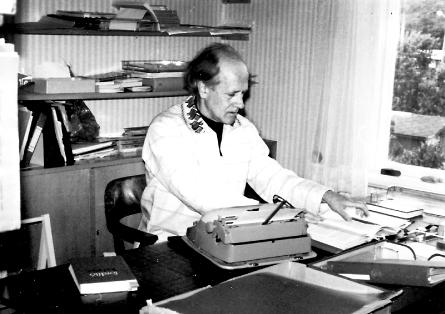

Erik Gunnemark. (

Courtesy of Dan Gunnemark

)

His theory of hyperpolyglot abilities was a simple guess: they must have photographic memories. “This seems to be the only explanation why some superpolyglots ‘know’ more than fifty languages although they can’t speak more than half of them (or less),” he wrote.

This was before I’d learned enough about hyperpolyglots to generalize about them, so his

statement seemed rather bold to me at the time. It was more sensible to assume that they popped up randomly in the population, at the same frequency as other types of eccentrics. I thought, he knows more than I do. Maybe he’s right.

Something else he wrote stopped me cold.

“On the whole one should concentrate on

modern

polyglots, usually born after 1900,” he wrote. “That means that Mezzofanti

must never be mentioned; he has nothing to do with polyglottery as a science—may be regarded as a mythical person.”

A mythical person? This didn’t make sense. I’d seen Mezzofanti’s handwriting, his papers, his letters. Did Gunnemark know something about Mezzofanti that I didn’t?

I would never get an answer. By the time I wrote him back to ask, the Swede had passed away after an extended illness.

Chapter 7

T

he one language accumulator that Dick Hudson knew about, Christopher, isn’t someone you can call up for an interview. His answers tend to be monosyllabic, and he’s not known as much of a conversationalist, whether in English (his mother tongue), or in his twenty or so other languages.

*

Brain-damaged, Christopher can’t do simple self-care tasks; he could never hold a job. His performance

IQ is very low (he’s never scored higher than 76) and has a mental age of nine. Remarkably, though, he has a knack for learning languages.

He spends much less time at languages than one would think. “He spends most of his waking hours digging in the garden, working in the [wool] carding shop, reading newspapers, listening to music and indulging in a variety of other occupations,” wrote University

of College London linguist Neil Smith and collaborator Ianthi-Maria Tsimpli, at the Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, in

The Mind of a Savant: Language Learning and Modularity,

their first book about Christopher’s language abilities.

Perhaps it was Christopher’s mother’s bout with German measles early in her pregnancy. Perhaps it was the bad fall she had. Perhaps it was her long labor, during

which the nurses sent for oxygen. But in February 1962, six weeks after he was born, Christopher was diagnosed as brain-damaged. At six or seven years old, his fascination with foreign languages was triggered by watching the 1968 Mexico Olympics. He often pretended to be from a foreign country, wearing a towel as a turban or a matador’s cape. “He had a precocious talent, but he was also afflicted

with a minor speech defect, poor eyesight, and a degree of clumsiness that seemed to confirm the diagnosis of mental handicap,” wrote Smith and Tsimpli.

Though he’s never been formally diagnosed with autism, he displays many autistic traits. From the documentary films and photographs I’ve seen, he’s a short, very sweet-looking, shambling man with thick eyebrows and a dark moustache. Smith and

Tsimpli describe him as “socially unforthcoming” and “emotionally opaque.” He is uninterested in social formalities and unable to perceive what other people might be thinking.

Another trait of the autist is an obsessive interest in one topic: in Christopher’s case, it’s languages. In French and Spanish, Smith says that Christopher is fluent, and “quite fluent” in Greek. German is easy for him,

as is Dutch. Before his appearance on a Dutch television show, someone suggested that he might improve his “rudimentary” Dutch, so after a few days with a grammar and a dictionary, he was able to converse with people before and after the program, performing as so many linguistic virtuosos before him had. In his other languages, he’s accumulated huge amounts of vocabulary, which he learns with what

appears to be a voracious, bottomless memory. One time Smith and Tsimpli gave him an hour-long grammar lesson in Berber and left him some basic books. A month later, he remembered everything about the Berber lesson.

What’s also amazing is that Christopher can also switch among all of his languages quite deftly and translate to and from English with ease. (Going between other languages is harder

for him.) The point is, he’s not simply a memory prodigy. Yet when you read more deeply about what he can and can’t do, it’s not clear that he contributes to an understanding of what language-learning talent might look like.

It depends in part on how you define

talent

. If it means that someone learns new languages quickly, and also pays attention to the declensions and inflections of words and

making the elements in noun and verb phrases agree, then Christopher has a talent. On the other hand, if by “talent” you mean performing anywhere close to what native speakers do, he doesn’t qualify. In many of his languages, much of what he says is repetitive; his translations are imperfect, particularly in languages that are further from Romance and Germanic. As Smith and Tsimpli acknowledge,

though he’s fluent in just a few of his languages, Christopher doesn’t know any of them to a native-like degree.

Others have noted that his English, though that’s his mother tongue, isn’t native-like, if you consider understanding metaphors to be part of a native’s skill set. Phrases like “standing on the shoulders of giants” confound him. Some scientists have suggested that in order to comprehend

a metaphor, you have to know that someone intends a meaning other than a literal reference to giants’ shoulders.

Christopher also doesn’t learn new grammars completely. After four years of Greek lessons, for instance, he grew his vocabulary, became more fluent, and reduced his errors. Yet he didn’t get better at distinguishing syntactically good from bad sentences. Normal second-language learners

have a harder time with the structure of words than with the structure of sentences; Christopher was the opposite. He’s genuinely obsessed—and genuinely excellent at—the mechanisms of constructing words, especially their spellings. He can also use four writing systems. Given a newspaper in one of his languages, he selects words and identifies parts of speech and other properties.

The biggest

limitation—and the one that may provide the true measure of what he can do—is that in most of his foreign languages, his English grammar influences what he says or translates. When asked to translate, “Who can speak German?” he answered with

“Wer kann sprechen Deutsch

?

”

not

“Wer kann Deutsch sprechen?”

It’s as if his English is just ventriloquizing in other languages.

As Smith and Tsimpli put

it, “It is not too inaccurate to suggest that Christopher’s syntax is basically English with a range of alternative veneers.” The technical word is a

calque—

a word-for-word translation from one language to another. (One well-known example is the English

calque “long time no see” of the Mandarin

hao jiu bu jian

.) In languages like Dutch and German (with a syntax and a word order very close to that

of English), the learner can calque away and remain intelligible; the further a language’s word order gets from English, the bigger impediment calquing becomes to being understood (and not sounding absurd). This echoes a folk sentiment about polyglots in Norwegian that someone told me:

Hvis en nordman hævder at han snakker syv språk, så er seks af dem norsk.

(If a Norwegian claims to be able to

speak seven languages, six of them are Norwegian.)

Recently Smith, Tsimpli, and some colleagues gave Christopher another kind of linguistic workout by teaching him British Sign Language (BSL), an experiment they document in their second book about him,

The Signs of a Savant: Language Against the Odds

. A sign language is an intriguing challenge. Where a speaker produces a strict string of sounds,

a signer often assembles multiple bits of meaning in the same moment of time. This makes calquing of the sort that Christopher does in other languages more obvious. Also, a system requiring manual dexterity and eye gaze was a challenge for a man with limits in each.

Christopher’s abilities were compared to those to a group of university language students who had tested well on a written test

of grammar in foreign languages. His understanding of BSL was good. Yet he had difficulty bringing his talents, whatever they are, to BSL. He had difficulty learning to use grammatical functions that required precise hand control. He developed eye contact with his teacher, but because he doesn’t generally look at faces, he misses the facial movements that BSL uses to signal negation or ask questions

like “What?” or “Where?” The normal learners were about as good as Christopher was in BSL.

From the beginning, Smith and Tsimpli hadn’t been interested in hyperpolyglottism itself, so they didn’t nail down in what way Christopher might be talented (at least in spoken and written languages). The theoretical fish they looked to fry concerned “modularity”—the idea that language is a separate function

in the brain. It is thought to be so separate that someone with asymmetric cognitive faculties (like Christopher) could have mostly intact language. Modularity was interesting in itself; so was the nature of thought, and whether or not language could be unique to humans or not. Such claims about modularity were

a red flag for critics, who dove at Smith and Tsimpli’s conclusions about Christopher

in the earlier book. Debunking the analysis of Christopher would take down the argument about modularity, too.

Some weren’t convinced that Christopher had, in fact, an intact language faculty, because he was so limited in English. (Smith argues that the structures of English in Christopher’s head were intact, which meant he is still a good example of modularity. His communication failures aren’t

governed by what Smith locates in the “language faculty.”) Other critics disputed that Christopher qualified as a savant, or that his fascination with languages was so remarkable. A survey of autistic savants from the 1970s showed that 19 out of 119 children were similarly obsessed with language forms. The survey turned up one child who sounded like Christopher, described by his parents as someone

with “a working knowledge of French, Spanish, Japanese, and Russian—knows at least the alphabet and pronunciation of Arabic, Hebrew, and several others.” (Many more people on the autistic spectrum are fascinated by machines, however, than by languages.)

Others commented that Christopher didn’t have a linguistic ability as much as a powerful talent for recognizing patterns. Only coincidentally

was this proficiency attuned to language, specifically words. He was also boosted by a powerful rote memory, considered one hallmark of autistic savants (said to be true because they remember what they see or hear without consciously thinking about what they’re taking in. Overall, Christopher’s memory profile, especially in working memory, is very strange). Both together give him analytic ability

as well as recall and performance. Yet, because he makes so many mistakes and can’t break away from English sentence patterns, “it would appear that Christopher is not so much a successful learner of languages [in the strict sense] as he is an obsessive accumulator of minutiae that happen to be linguistic in nature,” wrote one reviewer of

The Mind of a Savant.