Babel No More (12 page)

Authors: Michael Erard

Hudson was stymied.

Even if the feats of successful language learners are no longer explained through mystical sources—whether visits from angels or pacts with demons—we can’t ignore how some people are

faster learners and better users of their languages. Perhaps they can read shades of meaning more acutely, even mimicking sounds more exactly. Some of these people, who are on the high end of a normal curve, count

as experts. Yet others go far, far beyond this. How to explain this?

As he told me in a series of exchanges by email and phone, Hudson himself worked hard to learn various languages before traveling to the places they were spoken. He’d put in the required time on task. Yet after coming home, he found that his abilities rapidly and inevitably dwindled. Others learned faster and kept their knowledge

longer than he did. How did hyperpolyglots retain their skills? Could average language learners do the same?

Hudson was also alarmed by a negative trend in foreign-language education in Britain. Politicians lectured Britons on learning languages so they could get jobs in the European Union, while universities removed foreign-language requirements and shut down language departments when enrollments

dropped. Further, the government was constantly exporting English teachers, textbooks, courses, and programs, helping the country to earn £1.3 billion a year. In other words, learning languages was for citizens of other countries—who would then compete with Britons for jobs. The irony was underscored by the fact that by 2005, immigrants had transformed London into a place where at least 307

languages are spoken, making the capital of one of the most monolingual countries in the European Union the most multilingual city on the planet. A new approach to foreign-language education was direly needed.

Meanwhile, in the United States, a long-documented shortage of language analysts in US intelligence agencies meant that evidence of an imminent terrorist attack on September 11, 2001, sat

undiscovered in a queue until much too late. As it plotted its counterterrorism strategy, the US government was in a bind: unwilling to trust intelligence work to recent immigrants (especially ones from the same cultural groups that al-Qaeda drew from), the national fear of anything foreign had long snuffed out the immigrant-family languages it now desperately needed for a range of government functions.

Coupled with a peacetime vacuum of political will to build a linguistically expert workforce,

these trends, some of which dated back decades, ruined some of the country’s greatest human resources: linguistic fluency and cultural knowledge. Experts had long warned of such a shortage; in 1980, Senator Paul Simon published a searing jeremiad,

The Tongue-Tied American: Confronting the Foreign Language Crisis

. Yet the necessary funding for something as intangible as language could be mobilized only by a crisis.

The problems ran much deeper, though. Failing to produce enough language experts for government and business was considered the fault of the educational system. Yet success in language learning, whenever it occurred, was seen as the product of intense self-fashioning; it was, by and

large, an individual’s project. Such a view threw up barriers to connecting teachers and learners in ways that would make their efforts sustainable and promote brain plasticity. It also voided any legitimate role for government, which would be the prime beneficiary of expanded linguistic skills. The result was a profound inability to go about building more cognitive capital in the society around foreign-language

learning.

As Hudson saw it, cultural blindness, social inertia, and political inaction stood in the way of the language learning that the British and the Americans needed to do. Perhaps the way forward could be found in the methods or gifts of high-performing language learners, Hudson thought. They’re the Olympic athletes of languages. “If we understood how the gold medalists got their talent,”

he told me, “then we might know better how to teach ordinary people to speak more languages.”

Was this true? He’d have to meet some gold medalists to find out.

Chapter 6

E

very so often over the next several years, Hudson emailed me the name of another hyperpolyglot.

Have you ever heard of Harold Williams?

I’d write him back:

I have

(Williams was a New Zealand journalist, said to know fifty-eight languages.)

What about George Campbell

? Yes, he was a scholar from Scotland who could “speak and write fluently in at least 44 languages and had a working knowledge

of perhaps 20 others,” read his

Washington Post

obituary.

One drawback loomed: Hudson couldn’t hook me up with a real, living hyperpolyglot—he’d never met one. And in that, we were equal. At the time, little information about them had shown up online. Now you can easily go to YouTube and find videos of people rattling off messages in eight or ten languages, but when I began my research, I could

only hope that such virtual communities existed, and the Wikipedia entries on famous polyglots hadn’t yet been written, squabbled over, or removed.

A recurring frustration was that the modern scientific literature was nearly silent on the topic, except in decades-old studies about how trauma or disease in the brain damages a person’s ability in one or more of their spoken languages. The best

example, an article by an A. Leischner from 1948, originally in German, references Georg

Sauerwein (1831–1904), a German who apparently could speak and write twenty-six languages (though “otherwise he was rather untalented,” Leischner quipped). Others Leischner called “very talented.” He was trying to understand the principles that ordered languages in a person’s brain by seeing which languages

were affected by strokes. It seemed hyperpolyglots were most interesting when they were no longer so.

The trail of apocrypha about language-learning talents can most reliably be picked up in newspapers, especially in the obituaries. In a newspaper archive, I discovered the tale of Elizabeth Kulman, a girl born in St. Petersburg in 1809, who resolved to become the Russian Mezzofanti. Before she

reached the age of sixteen, she spoke Greek, Spanish, Portuguese, “Salamanic,” German, and Russian. All told, she “mastered” eleven languages; she spoke fluently in eight, it was said. But Elizabeth never had the chance to scale the Mezzofantian heights she desired. From the time she was eleven years old, she’d slept no more than six hours a night to allow for more time to study. The lack of sleep

made her frail, and at seventeen, she died.

In the same archive was the tale of Ira T. O’Brien, an American blacksmith in Rome, Georgia, who was nicknamed “Rome’s Learned Vulcan.” According to the 1898 report, O’Brien spoke Greek, German, French, Spanish, Italian, Latin, and other languages. A quiet, unassuming man, he was described as having “gigantic stature” and “prodigious strength.” But

the writer questioned “why a man of his unquestioned learning and talents should be content to serve the humble role of a blacksmith.”

One answer was that, some sixty years earlier, the humble role of blacksmith had been a ticket to the big time. In 1838, the governor of Massachusetts, William Everett, in a speech to a group of educators, mentioned a “learned blacksmith” from Connecticut named

Elihu Burritt (1810–1879) who had taught himself fifty languages. Burritt, then twenty-eight years old, had a compulsion for only two things, manual labor and reading foreign languages. He always told people that he hadn’t sought any of the attention or accolades that resulted from Everett’s speech. During the decade he spent teaching himself to read a number of foreign languages, in what appeared

to be an attempt

to surpass the scholarly achievements of his dead older brother, he supported himself by forging garden hoes and cowbells. He was proud to say (and probably said more than was necessary) that he carried his Greek and Latin grammars to work in his hat and studied them during breaks. But languages and garden hoes didn’t pay. Burritt, seeking translation work, wrote to a prominent

Worcester citizen; the letter was published in the newspaper, where it caught Governor Everett’s eye. The poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow arranged for him to study at Harvard, but Burritt declined, saying that if he didn’t work at the forge, he’d get ill. Before Paul Bunyan and Johnny Appleseed, Burritt was a shining example of American self-making and the faith in self-improvement, all in service

of what would later seem a very un-American pursuit.

Predictably, his linguistic achievement has been mostly forgotten. When I went to the New Britain, Connecticut, public library to look at the Burritt collection, the librarians said that no one came to research what he did (or claimed to do) with languages; the scholars who came were mostly interested in his later work advocating the abolition

of the military. After I asked to look in the bookcases lining the small special collections room, the librarians were surprised to find, behind the smeary glass of the doors, his language books: a Hindustani New Testament, a Tamil grammar, a Portuguese dictionary, a tiny, brittle-paged copy of

The Odyssey

in Greek, wrapped in oilcloth and tied with stiff red cord. Burritt had delved into Portuguese,

Flemish, Danish, Swedish, Norwegian, Icelandic, Welsh, Gaelic, and Celtic. Russian and other Slavic languages followed, then Syriac, Chaldaic, Samaritan, and Ethiopic. One of his biographers, Peter Tolis, granted Burritt thirty languages;

Knight’s Cyclopedia of Biography

gave him nineteen.

*

When I visited the American Antiquarian Society in Worcester, which Burritt used as a resource, I found

that it had had grammars and dictionaries in far fewer exotic languages than he claimed. In 1837, the collection contained books in thirty-one languages; in eight languages, the holdings consisted solely of copies of the New

Testament. Interestingly, the society’s library also contained a number of books in Native American languages such as Massachusett and Narraganset. Burritt never bothered

to learn these—to a Yankee barely out of the backwoods himself, the languages of New World natives wouldn’t have been as exotic, or have conferred on him as much stature, as Chaldean or Samaritan. “His compulsive and erratic study of languages was not an end in itself,” wrote Peter Tolis, “but a means of social escalation, a kind of intellectual stunt he used to emancipate himself from the blacksmith

shop.”

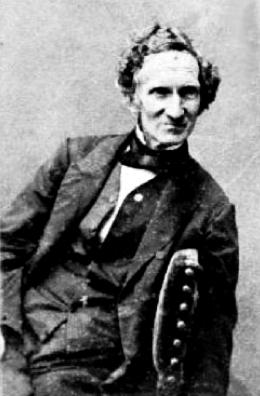

Elihu Burritt.

Burritt never claimed to speak his languages—only to read them. During his most intense decade of study, he spent four hours a day (one at lunch, three in the evening) studying and marked his progress in a ledger like so:

June 9.—68 lines of Hebrew; 50 lines of Celtic; 40 pages of

French; 3 hours studying Syriac; 9 hours of forging.

or:

June 10.—100 lines of Hebrew; 85 pages of French;

4 services at church; Bible-class at noon.

When Burritt was thirty-three years old, he abruptly quit his languages and his tools, realizing, as he told a hometown crowd once, that “there was something to live for besides the mere gratification of a desire to learn, that there were words to be spoken with the living tongue and earnest heart for great principles of truth and

righteousness.”

Leveraging his improbable linguistic celebrity, he became a reformer for peace, abolition, and cheaper postage for transatlantic letters and eventually wrote thirty books. It’s said he was so famous, he never paid for a hotel room or riverboat passage. Later in life, he returned to languages, promoting the wonders of Sanskrit to young women in New Britain. How I would have loved

to peek in on Mr. Burritt’s Sanskrit Lessons for Young Yankee Ladies, the petticoats and scrimshaw in the glow of Burritt’s enthusiasm. After he died in 1879, friends praised him for his “child-like and beautiful personality.”

In 1841, a plaster cast of Burritt’s skull was taken by prominent phrenologist Lorenzo Niles Fowler. This was perhaps the first instance in which a polyglot’s abilities

were given a specific location in the head, albeit by phrenology, which was fashionable for a time but eventually was lambasted as a pseudoscience. Phrenologists regarded the surface of a person’s skull as a map to his or her intelligence, personality, and character. The phrenologist’s job was to decode the relative size and shape of the brain’s discrete areas, thirty-seven in all, with names like

“veneration” and “agreeableness,” stretching from the nape of the neck up to the nose, and down the temples around the eyes to the nose.

Here’s the drawing of Burritt’s head from Fowler’s publication: