Babel No More (13 page)

Authors: Michael Erard

Elihu Burritt in profile.

On the phrenological map, the “Language” organ makes up part of the territory around the eyes, though this wasn’t notably prominent on Burritt. But the author apparently knew that the blacksmith didn’t

speak

fifty languages and could only read them, so he credited the organ of Form with

the blacksmith’s gifts. In his write-up for a phrenological journal, the phrenologist

(who may or may not have been Lorenzo Fowler himself) reported his astonishment at the shape of Burritt’s Form, “and the power it confers of retaining the shapes of letters and words constitutes his principal aid in his lingual pursuits,” he wrote. According to phrenologists, Form is where memory of figures, like shapes and faces, spellings, and images were contained. To remember the words,

Burritt relied on the faculty of Eventuality, which was “immense.” In Burritt, it “confers a retentiveness of historical and literary memory, probably unequaled in the world,” Fowler wrote. “He apparently knows EVERY thing.” I was never able to track down Burritt’s skull cast, which has, I imagine, suffered the same fate as Burritt himself.

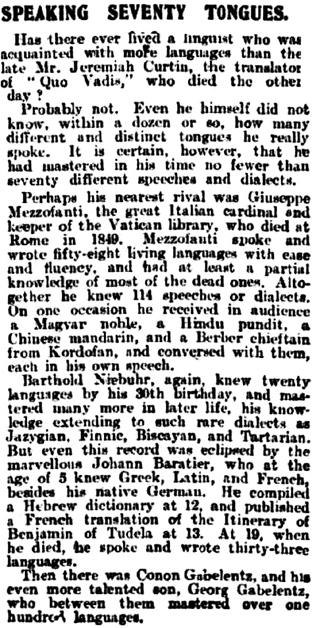

In an Australian newspaper archive, I also found this

appraisal of the American Jeremiah Curtin, Mezzofanti, and other polyglots. I love the way these accounts make each one sound more accomplished than the previous.

Newspaper article about polyglots.

Here and there in my library explorations I found hyped, exploited children, one of the most colorful of whom was Winifred Sackville Stoner Jr. (1902–1983). In 1928,

Time

magazine reported that Cherie (her nickname) had mastered thirteen languages by the age of nine, the same year she passed the entrance examination for

Stanford University.

*

Her only rival

for the public’s fascination with child prodigies was William James Sidis (1898–1944), whose admission to Harvard at twelve as a math and philosophy prodigy made him a prime example of nurture by pushy parenting. (Sidis died at the age of forty-four, having lived the second half of his life doing menial jobs.

†

) Cherie was a product of the same.

Her mother, the strong-willed Winifred Sackville

Stoner, touted the “natural education” that developed her daughter’s genius: putting colorful pictures over the baby’s crib, dispensing with nursery rhymes she called “silly,” and reading her the Bible, mythology, and Latin classics. Baby Cherie was also given a typewriter to create stories and poems (which Sidis was also doing at the age of four), on which she composed the nineteen-couplet historical

poem that starts, “In fourteen hundred ninety-two, Columbus sailed the ocean blue / And found this land, land of the Free, beloved by you, beloved by me.”

In 1921, Mother Stoner (as she was called) would attempt to hush the news that her sixteen-year-old genius offspring had met the older globe-trotting French count Charles Philippe de Bruche and married him thirteen days later. By all appearances,

the count was the perfect man for the teen prodigy—a swashbuckling adventurer who searched for lost manuscripts and spoke seventeen languages. Sadly, he died in Mexico City in 1922, soon after Cherie and probably her parents had discovered that he wasn’t an aristocrat but rather a penniless con artist named Charles Philip Christian Bruch—and to top off his deception, he probably didn’t speak

those seventeen languages either.

A couple of years later, the two Winifreds embarked on a world tour to “find geniuses.” They were accompanied by six-year-old New Yorker

Lorraine Jaillet, a “genius” who spoke six languages. (No word on how many geniuses they found.) Cherie married and divorced again and was on the verge of yet another engagement in 1930, when a mysteriously resurrected Bruch

showed up. Cherie dismissed him, and to be safe, had her marriage annulled. After one last media splash in 1931, occasioned by her lawsuit against a lover, Cherie lived quietly in New York City for the rest of her days. One joke after her third marriage was that she could speak eighteen languages but couldn’t say “no” in any of them.

Through my connections to linguists, I knew about the less

dramatic life of Ken Hale, a highly regarded linguist at MIT and a champion of minority languages around the world, who died in 2001. His colleagues attribute fifty languages to him. He began learning them as a boarding school student in Arizona, first picking up Spanish, then Jemez and Hopi (two indigenous languages of the Southwest) from his roommates. After college, he and the woman who became

his wife, Sally, went to tuberculosis sanitariums in Arizona to tape-record messages from members of tribes who couldn’t write letters to their distant families.

Hale wasn’t the only linguist with a facility for being able to rapidly find a way to say a lot of things in very many unrelated languages. He does, however, seem to be unique in the number of tales told about his feats. Everyone I speak

to at linguistic conferences seems to have a Ken Hale story, or to know someone who did. Once, he spoke Irish to a clerk at the Irish embassy until she begged him to stop; her Irish wasn’t as good as his. After watching the television miniseries

Shogun

with subtitles, he was able to speak Japanese. While doing fieldwork in Australia, he and an Aboriginal collaborator named George Robertson Jampijinpa

would show up in a village at 10 a.m. to begin working on the local language, and by lunchtime Hale (who’d never heard the language before) would be conversing fluently. This kind of admiring lore was matched by his colleagues’ regard for his scholarly work, “which almost certainly could not have been carried out by a fieldworker who was not a natural polyglot,” wrote Victor Golla, another

linguist, or “by someone who was not virtually a native speaker himself.” The linguists didn’t seem to care that Hale himself hated the myth. “Here we go again,” he was known to say when it came up.

One useful way to think about what a hyperpolyglot can do is to

see which languages he “speaks” and which ones he “talks in.” Hale would say he could speak only three (English, Spanish, and Warlpiri,

an aboriginal Australian language). The others, he only talked in—he could say a few things in a few topics—but he didn’t know how to communicate in all of life’s relevant situations, like walking through a doorway with someone. The bits of language he possessed didn’t include bits like “After you, Alphonse” or “Age before beauty.” In some languages it was hard to know how to say something as

seemingly simple as “yes.” These were some of his hallmarks for “speaking” a language, and Hale claimed he didn’t possess them. What about the time he took a

Teach Yourself Finnish

book on a plane flight and landed in Helsinki using Finnish? That was just “talking in” the language. (The same story is told about Hale and his use of Norwegian.)

One of his sons, Ezra, explains that his father used

languages in a few ways. It made mundane things exciting; it broke the ice in new situations; and it insulated him and helped him overcome his shyness. “I remember one time I decided to do a video of him and said we should go down to the audiovisual department and get a video recorder,” Ezra told me. “His reaction was something like ‘Are you crazy? We can’t just go down there, you can’t just do

that.’ But when we got there, there were three people standing around all excited to hear about our planned project. Dad just stood around quietly and somewhat awkwardly.

“Yet if the video equipment had been at the Chinese embassy he would have taken the lead, gone in there, spoken Mandarin or preferably some obscure dialect, and walked out with the AV equipment without thinking twice about it.

But because there was no obvious common ground with whoever was working at the MIT AV department, he was comically afraid of going down there.”

As in the case of Mezzofanti, Hale was caught in a self-reinforcing spiral of being legendary, such that the reality of his “something and something” abilities in dozens of languages became an “all or nothing” reputation through the alchemy of awe (or

envy). His gift became a professional asset, which led to increasingly public performances of his virtuosity at a high-profile university; then his scholarly reputation and his friendly generosity pulled more and more languages, speakers, and learning opportunities his way, creating more opportunities for performances

to be seen and heard by more people, who lent their exaggerations to the reports.

Underneath the reputation, though, Hale was shy and modest, which former colleagues cited to explain why he denied the genius myth. To them, he just didn’t want to own up to it. More likely, the refusal was real, and he probably didn’t want to be seen as a freak. Still, people wanted to believe—so much so that his denials were rejected to his face, as in a 1996 interview.

Hale was asked: “You

know that you are some sort of a legend, when it comes to learning languages—the number of languages you know, the speed with which you learn new ones. Can you give us some tips as to how to go about learning a new language?”

“A legend! It’s a complete myth!” Hale said. “Let me take this opportunity to dispel that myth! I am going to tell you the truth. Don’t delete this part!”

“Promise,” said

the interviewer.

“The truth is, I only know three languages and one of them is English. So all I really learned was two languages: Warlpiri and Spanish. Those are the only two that I feel like I know.”

“How about Navajo?”

“I know a lot about Navajo, but I can’t converse in Navajo.”

“That is not true.”

“It

is

true. I can’t converse in Navajo. I can say a lot of things that make people think

I can converse, but when somebody talks back, I can’t respond to them in an adequate way. Saying things is totally different from conversing. I can say many things in different languages, but conversing is a different thing. Talking a language is really different from knowing something about a language.”

Then he shared some of the tips and tricks he’d honed for building his linguistic patchwork.

First, he said, you want to get a handle on the sounds, so get a native speaker and go through words for body parts, animals, trees, things in the environment. Fifty words would give you the basics, more if it was a tone language. Then ask for nouns and verbs, and start building sentences. Learn how to build a noun phrase. Elicit items actively; don’t rely on a textbook’s prechewed material. “I

learn ten times more by just doing what I just told you, because then I can hear it. I have to hear it. I can’t just look at it,” Hale said.

He also recommended that one learn how to construct complex sentences early. In school these are usually taught late, but because they’re regularly patterned, they can be easy. So, he said, learn how to make relative clauses right away, because with a relative

clause, you can say “the thing that you hit a baseball with” if you don’t know the word for

bat

. I’ve never taken this advice, but if I were ever to try to learn a foreign language again, I know I would find this construction handy. Of course, speaking in more complex sentences also sounds impressive.

As far as I could tell, no one had ever assessed his language abilities or measured his cognitive

skills. “Think of Ken’s ability to learn languages the way you might think of Mozart’s ability,” Samuel Jay Keyser, another MIT linguist, wrote me in an email. “Ken’s ability to learn language was much like that, an amazing gift the neurological basis of which is a mystery.”

I found hyperpolyglots fascinating icons of a cultural desire to feel connected in the modern world through foreign languages.

An Austrian-born, New York–based artist named Rainer Ganahl has helped me understand how these desires arise and the shape they take.

Ganahl is a gangly-limbed man with wild dark hair, which I know from watching the videos he’s made; the emails he’s sent me are so extravagantly misspelled that I suppose he’s either constantly in a rush or typing from a bicycle. Since 1992, he’s created various

installation pieces and video projects based on his learning of Japanese, Greek, Arabic, Korean, Chinese, and other languages. He has videotaped himself reading Arabic and Chinese and once put his Japanese study materials, including a desk, on display. He called the boxes of videotape, five hundred hours of it, a sculpture. At first, I was surprised to find that he wasn’t trying to become fluent

in any of these languages. And that he admitted this. Rather, Ganahl’s art puts his experiences of becoming a linguistic outsider into a concrete form that can be inspected and critiqued. This was crucial. Until 1992, he was interested in language acquisition and could speak five languages, then made language learning itself his artwork, once he faced the fact that he wouldn’t be fully perfect in

every language. He considers himself a “semiprofessionaldilettante.” “I can say

I am not a terrorist

in eleven languages,” he quips in one video. (He stands by his misspellings, too. “It s in fact often poetic,” he wrote to me once. “And often a bit of a walk on the wild provocative line.”)

His 1995 essay, “Travelling Linguistics,” might serve as something of a manifesto for many hyperpolyglots

and high-intensity language learners someday. In it, Ganahl puts a larger historical frame around his own attempts to move away from his mother tongue. “There are many reasons why somebody ends up speaking or learning a ‘foreign language’ voluntarily or involuntarily,” he wrote. “I would like to look at some reasons that may in fact be interrelated: educational, political, colonial, migrational

and psychological reasons.”