Baseball's Hall of Fame or Hall of Shame (19 page)

The thing about Hafey, though, is that he was a full-time regular for only six seasons, totaling more than 500 at-bats only four times, and topping 400 plate appearances only two other times. As a result, his career numbers pale by comparison to those of most legitimate Hall of Famers. In addition, like Manush, he was never considered to be among the very best players in the game, or even, for that matter, in his own league. He was also ranked well behind Al Simmons among leftfielders throughout his career.

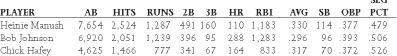

Let’s take a look at the career numbers of both Manush and Hafey, alongside those of Bob Johnson, the man who succeeded Simmons in leftfield for the Philadelphia Athletics, and who is not in the Hall of Fame:

Looking at this graphic, several things become quite apparent. First, while Hafey was a very good hitter, he just didn’t do enough to be considered a legitimate Hall of Famer. Other than his .317 batting average and .526 slugging percentage—both of which were somewhat inflated by the era in which he played—none of his numbers are even close to being Hall of Fame worthy. It is also apparent that Johnson was easily the most productive and powerful hitter of the three. Playing from 1933 to 1945, in somewhat less of a hitter’s era, he put up the most impressive numbers. In approximately 700 fewer at-bats, Johnson hit more than twice as many homers as Manush, knocked in 40 more runs, scored almost as many runs, and finished with a higher slugging percentage. His batting average was considerably lower, but much of that discrepancy is due to the fact that Manush’s average was padded somewhat during the 1920s. In addition, due to his greater ability to draw bases on balls, Johnson finished with a higher on-base percentage despite his lower batting average. Manush had more doubles and triples, but Johnson was a far more dangerous hitter. He hit more than 30 homers three times, knocked in more than 100 runs eight times, scored more than 100 runs six times, and batted over .300 four times.

Johnson also does rather well using our Hall of Fame criteria. Although it could not be said that he was among the very best players in the game for most of his career, he was arguably the best leftfielder in the American League from 1935 to 1938. He was also selected to the All-Star Team eight times, and he finished in the top 10 in the MVP voting three times.

Once again, this is not to suggest that someone who is not in the Hall of Fame should be. Johnson probably does not deserve to be in. However, he belongs just as much as Manush, and more than Hafey. Of course, Frankie Frisch, when he was on the Veterans Committee, had a lot to do with his former Cardinals teammate being elected in 1971. As for Manush, he was not a bad choice, but his selection should also be looked upon with a great deal of skepticism.

Zack Wheat

Before ending his career with the Philadelphia Athletics in 1927, Zack Wheat spent his first 18 seasons playing for the Brooklyn Dodgers. For much of the second decade of the 20th century, Wheat was considered to be one of the top sluggers in the National League, even though he never hit more than nine home runs or drove in more than 89 runs during that period. He was also one of the league’s top three outfielders for much of the decade, batting over .300 six times and finishing in double-digits in triples seven times. When a livelier ball was put into play for the first time in 1920, Wheat’s productivity, along with that of virtually every other major league hitter, increased dramatically. During the 1920s, he failed to bat over .300 only once, twice reaching the .375 mark. He also reached double-digits in home runs four times, knocked in over 100 runs twice, scored more than 100 runs once, collected more than 200 hits three times, and reached double-digits in triples four more times.

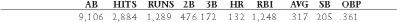

However, while Wheat was thought of as being one of the top players in the National League for much of his first ten years with the Dodgers, he was never looked upon as being one of the five or six best players in the game. He wasn’t even considered to be one of the four or five best outfielders (he was ranked well behind Ty Cobb, Tris Speaker, Shoeless Joe Jackson, and Sam Crawford). Even though Wheat became a more productive hitter during the first half of the 1920s, there were many outfielders who were far more productive—Babe Ruth, Harry Heilmann, Bobby Veach, Ken Williams, Cy Williams, Cobb, and Speaker, just to name a few. While Wheat did hit .375 twice during the decade, he failed to win the batting title either year (Rogers Hornsby won it both times). In fact, Wheat was a league-leader only twice during his career, winning the batting title once and leading the league in slugging percentage once. Here are his career numbers:

Those are good numbers, probably strong enough to earn him serious consideration for induction into the Hall of Fame. Consider, though, that this is what they look like if they are split between the figures he accumulated prior to 1920 and those he compiled during the 1920s:

This is an indication of how much greater Wheat’s productivity was during the 1920s, and what kind of impact hitting with a livelier ball had on him. While his power numbers could be expected to jump drastically during this period, note the discrepancy in his batting averages. From this, it would seem that Wheat was a good, solid player, but that he benefited greatly from playing in one of the greatest hitting decades in baseball history. As a result, Wheat would probably fall just short of being Hall of Fame worthy.

Willie Mays/Ty Cobb

Mays and Cobb are at the top of the list of great centerfielders whose Hall of Fame credentials would not be questioned by anyone.

Many people consider Willie Mays to be the greatest all-around player in baseball history. There is nothing on a ball field he could not do. He had great power, was a lifetime .300 hitter, was a superb baserunner, and was one of the finest defensive centerfielders in the history of the game. As if his 660 career home runs, 1,903 runs batted in, 3,283 hits, and 11 Gold Gloves weren’t enough, he was also the first man to hit 300 home runs and steal 300 bases. He led the National League in home runs four times, batting average once, triples three times, slugging percentage five times, runs scored and on-base percentage two times each, and stolen bases four times.

From 1954 to 1966, Mays was one of the five best players in baseball and, in most of those years, the best centerfielder in the game. In several of those seasons, he was viewed as being the sport’s greatest player. He certainly was just that in 1954, 1955, 1962, 1964, and 1965. In the first of those seasons, Mays hit 41 homers, knocked in 110 runs, scored 119 more, and led the N.L. with a .345 batting average, .667 slugging percentage and 13 triples, en route to leading the Giants to the world championship and winning the first of his two Most Valuable Player Awards. The following season, he hit 51 homers, knocked in 127 runs, and batted .319. In 1962, he led the league with 49 homers, drove in 141 runs, batted .304, and scored 130 runs to finish second to Maury Wills in the MVP voting. Two years later, he hit 47 home runs, knocked in 111 runs, scored 121 others, and finished with a batting average of .296. Mays won the MVP Award for the second time in 1965, when he hit 52 homers and finished with 112 runs batted in, 118 runs scored, and a .317 batting average.

In all, Mays finished in the top five in the MVP voting an astonishing nine times during his career and was selected to the All-Star Team twenty times.

From 1907 to 1919, Ty Cobb was considered to be the most dominant player in baseball. During that 13-year period, he won ten batting titles and hit .383, .368, and .371 in the three seasons he failed to do so. He batted over .350 in all but one of those seasons, topping the .400-mark twice. Over that stretch he also collected more than 200 hits seven times, knocked in over 100 runs five times, scored more than 100 runs seven times, stole over 50 bases eight times, finished in double-digits in triples every season, won the American League’s triple crown once, and was also named its MVP once.

In addition to his ten batting titles, during his career Cobb led the league in stolen bases six times, runs batted in four times, triples four times, doubles three times, hits eight times, runs scored five times, on-base percentage six times, and slugging percentage eight times. He finished his career with 1,937 runs batted in, 2,246 runs scored, 295 triples, 724 doubles, 4,189 hits, 891 stolen bases, and the highest batting average (.367) of any player in baseball history. Although many of his records have since been broken, when Cobb retired in 1928 he held almost every major career and single season batting and base-running record.

Yet, despite his incredible list of achievements, if the Hall of Fame voters truly considered “character,” “sportsmanship,” and “integrity” when evaluating potential candidates during the selection process, they would have thought twice before admitting Cobb, instead of making him one of the five original members in 1936. Cobb was a bitter, contentious, antagonistic, and violent man, who felt stronger than most about keeping black players out of the major leagues. We will take a closer look at this side of Cobb in a later chapter, but, suffice to say, the Hall of Fame clearly is more stringent at some times than at others in its admissions policy.

Joe DiMaggio/Mickey Mantle

The two greatest centerfielders in New York Yankees history were also among the five greatest of all-time.

For virtually his entire career, Joe DiMaggio was the best centerfielder in baseball, and among its five best players. In fact, from 1936 to 1942, prior to his three-year stint in the military, the young DiMaggio may very well have been the finest all-around player in baseball history. Certainly, from 1937 to 1941, and again in 1948, a valid case could be made for him being the best player in the game.

In 1937, DiMaggio led the American League with 46 home runs, knocked in 167 runs, scored 151 others, and batted .346, while compiling 418 total bases and 215 base hits. Only his teammate Lou Gehrig, Detroit’s Hank Greenberg, and the National League’s Joe Medwick had comparable seasons. The following year, DiMaggio hit 32 homers, knocked in 140 runs, and batted .324. However, he would probably have to be rated just behind Jimmie Foxx and Greenberg that year, since both men reached the 50-homer plateau. In 1939, DiMaggio won the first of his three Most Valuable Player Awards by leading the league with a .381 batting average, while hitting 30 homers and driving in 126 runs, despite missing more than 30 games due to injuries. He was clearly the best player in baseball that season and quite possibly the next year as well. In 1940, he won his second consecutive batting title, hitting .352 while collecting 31 homers and 133 runs batted in, to finish just behind Greenberg in the MVP voting. The following year, DiMaggio hit in 56 straight games, batted .357, hit 30 homers, drove in 125 runs, won his second Most Valuable Player Award, and vied with Ted Williams (who batted .406) for the title of greatest player in the game. After coming out of the service two years earlier, DiMaggio had another great season in 1948 when he led the league in homers (39) and runs batted in (155), while batting .320.

During his career, DiMaggio won three MVP Awards, two home run titles, three RBI crowns, and two batting championships. He was selected to the All-Star Team in each of his 13 big-league seasons, and was selected to

The Sporting News All-Star Team

eight times. In addition to his three MVP seasons, he finished in the top five in the voting three other times. One particularly amazing statistic about DiMaggio is that he hit 361 home runs and struck out only 369 times during his career.

Had Mickey Mantle taken better care of himself and been able to play most of his career injury-free, he may have gone on to become the greatest baseball player in history. As it is, he is generally considered to be one of the 15 greatest players of all-time. He was clearly the greatest switch-hitter in the history of the game, and he probably possessed the greatest combination of speed and power that the game has ever seen.

Although he never quite lived up to his full potential, Mantle’s 536 career home runs, 1,509 runs batted in, 1,677 runs scored, and .423 on-base percentage are all quite impressive figures. In spite of the constant pain and injuries he had to play through much of the time, Mantle was still one of the two or three best players in the American League for a good portion of his career, and among the five or six best in the game. From 1955 to 1958, then again, from 1960 to 1962, Mickey was one of the very best players in baseball. In fact, in at least three of those seasons, he may very well have been

the

best player in the game. Mickey’s greatest season came in 1956 when he won the first of his three Most Valuable Player Awards by leading the major leagues in home runs (52), runs batted in (130), batting average (.353), runs scored (132), and slugging percentage (.705). He became just the second player (Jimmie Foxx was the first) to hit 50 homers and win a batting title in the same season. He followed that up with another great year in 1957 by hitting 34 homers, knocking in 94 runs, batting .365, walking 146 times, and winning his second consecutive MVP Award. Mantle was again arguably the best player in the game in 1961, even though he was beaten out for MVP honors by his teammate Roger Maris. That year, Mantle hit 54 home runs, knocked in 128 runs, and batted .317.

In all, Mantle led the American League in home runs four times, runs batted in once, batting average once, runs scored six times, on-base percentage three times, slugging percentage four times, and walks five times. He won three Most Valuable Player Awards and finished in the top five in the voting five other times. Mantle was also selected to the American League All-Star Team a total of 16 times, and to

The Sporting News All-Star Team

six times.

Tris Speaker

During the second decade of the 20th century, only Ty Cobb prevented Tris Speaker from being widely acknowledged as the greatest player in the game. From 1910 to 1919, Speaker batted well over .300 in all but one season, topping the .340-mark five times. During that 10-year period, he finished in double-digits in triples nine times, collected more than 40 doubles four times, scored more than 100 runs four times, and led the American League in home runs and batting average once each. He was named the league’s Most Valuable Player in 1912 when, playing for the Boston Red Sox, he batted .383 and amassed 53 doubles. Speaker was also regarded as the finest defensive centerfielder in the game. In fact, to this day, many baseball experts consider him to be the greatest defensive centerfielder in baseball history.

In the 1920s, playing for the Cleveland Indians, Speaker continued to stand out as one of the finest all-around players in the game. With a livelier ball being used that decade, he batted over .360 five times, drove in over 100 runs twice, and became the only man to ever lead his league in doubles four straight years, from 1920 to 1923. His .345 career batting average, 222 triples, 1,882 runs scored, and 3,514 hits all place him in the top 10 all-time, and he is the career leader in doubles, with 792.

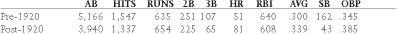

Oscar Charleston/Cool Papa Bell

Charleston and Bell were the two greatest outfielders in Negro League history and were generally regarded to be among the league’s five greatest players.

Oscar Charleston’s career in the Negro Leagues spanned 28 years, from 1915 to 1942. For much of that time, he was considered to be the league’s finest all-around player, rivaling Josh Gibson as its top slugger and Cool Papa Bell as its best centerfielder. In fact, during his career, Charleston was compared favorably to Tris Speaker as a fielder, Ty Cobb as a baserunner, and Babe Ruth as a hitter. Many who saw him play insisted there was never anyone better.

Charleston played for 12 different teams during his 28-year Negro League career. Among his numerous stops were two seasons with the Homestead Grays, for whom he performed in 1930 and 1931. The Grays’ 1931 squad is considered to be among the greatest baseball teams ever assembled. Joining Charleston on the roster were future Hall of Famers Josh Gibson, Smokey Joe Williams, and Jud Wilson. Charleston batted .380 for the Grays that year.