Baseball's Hall of Fame or Hall of Shame (18 page)

Yet, there are legitimate arguments that can be waged against the legitimacy of Rice’s 2009 induction into Cooperstown. Injuries caused his offensive production to fall off dramatically his last few seasons, leaving Rice with less-than overwhelming career totals of 382 home runs and 1,249 runs scored. He was not a particularly good baserunner, and he was generally considered to be a below-average fielder, with somewhat limited range and only fair instincts in the outfield.

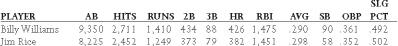

Nevertheless, supporters of Rice can also point to his eight appearances on the All-Star team. He also was a league-leader in a major statistical category a total of 13 times, and the majority of players who competed during his era consider Rice to be one of the most dominant figures of that period. Furthermore, his credentials are actually quite comparable to those of Billy Williams, who we previously identified as a legitimate Hall of Famer:

Williams finished slightly ahead of Rice in most offensive categories, but that was primarily because he accumulated 1,125 more at-bats during his career. Rice actually drove in runs at a faster pace and compiled a higher batting average and slugging percentage. Williams was an extremely consistent performer over the years, but Rice was the more dominant hitter. While Rice topped his league in a major statistical category a total of 13 times, Williams was a league-leader only five times. Williams placed in the top five in the MVP voting only twice, to Rice’s six top-five finishes, and Williams’ six appearances on the All-Star team were two fewer than Rice’s eight selections. Furthermore, while Williams had only three or four truly dominant seasons that could be classified as Hall-of-Fame caliber, Rice had at least six such campaigns. Therefore, while Rice should be viewed very much as a borderline Hall of Famer, his 2009 induction certainly does not lower the Hall’s standards in the least.

Jesse Burkett/Fred Clarke/Joe Kelley

These three players have been grouped together for two reasons. First, they were contemporaries of one another, each coming up to the majors during the last decade of the nineteenth century and playing through part, or all, of the first decade of the twentieth. Second, all three were very good players, although their career numbers were somewhat inflated by the rules that were in effect from 1893 to 1900. Let’s take a look at the career of each man:

Jesse Burkett came up with the New York Giants in 1890, but was traded at the end of the season to the Cleveland Spiders (who eventually became the St. Louis Cardinals), where he became a full-time outfielder in 1892. That season, he had a relatively good year, batting .275, scoring 119 runs, and collecting 14 triples. The following year, though, with the pitcher’s mound moved back to 60' 6" and batting averages throughout baseball soaring to record highs, Burkett’s numbers took a quantum leap as well. That season, he finished with an average of .348 and scored 145 runs. Over the next several seasons, Burkett was arguably the finest leadoff hitter in the game. From 1893 to 1901, he never batted any lower than .341, and he topped the .400-mark twice. Over that nine-year stretch, he failed to score at least 100 runs only once, surpassing the 140-mark four times and tallying a career-best 160 runs scored in 1896. He also collected more than 200 hits six times and stole more than 30 bases five times.

However, after being traded to the St. Louis Browns in 1902, Burkett never again hit any higher than .306. It is hard to say if his decline was more a reflection of the times, since pitchers came to dominate the game once more shortly after the turn of the century, or if it was more an indication that he was in the twilight of his career at that juncture. Either way, Burkett remained a full-time player over his final four seasons, totaling well over 500 at-bats each year. Therefore, the Browns must have felt that he had something left. Yet, he batted over .300 in only one of those years.

Still, during his career, Burkett led the league in batting and hits three times each, and in runs scored twice. In addition, his two seasons with a batting average in excess of .400, six seasons with more than 200 hits, and nine years with more than 100 runs scored are quite impressive, regardless of the era in which he played. Burkett was elected to the Hall of Fame by the Veterans Committee in 1946.

Fred Clarke came up to the Louisville Colonels in 1894 and remained with the team long after they became the Pittsburgh Pirates prior to the start of the 1900 season. In fact, Clarke served as player/manager of the team from 1897 until he retired at the end of the 1911 season. Thus, for the first seven years of his career, Clarke was a beneficiary of the rules changes that went into effect one year prior to his arrival in the big leagues. However, he spent the last ten years of his career hitting in the Deadball Era, when pitchers dominated the sport. Therefore, his numbers can probably be viewed without a great deal of skepticism.

Although Clarke was not a big run-producer, never having driven in more than 82 runs in any season, he was a fine hitter, topping the .300 mark eleven times during his career. As might be expected, he had his finest seasons during the last decade of the 19th century, posting averages of .347 in 1895, .390 in 1897, and .342 in 1899. However, Clarke did hit .351 in 1903, clearly indicating that he was a good hitter, regardless of the rules that were in effect at any particular time. In addition, he collected 200 hits twice, scored over 100 runs five times, and finished in double-digits in triples 14 times. During his career, though, Clarke only led the league once in triples, doubles, and slugging percentage. The Veterans Committee elected him to the Hall of Fame in 1945.

Joe Kelley played for five different teams during his 18-year career that spanned virtually all of the last decade of the nineteenth century, and the first decade of the twentieth. He was similar to Burkett and Clarke in that he was a fine hitter whose career batting average was aided immeasurably by playing during the 1890s. However, he differed from the other two men in that he was far superior as a run producer. During his career, Kelley knocked in over 100 runs five times, peaking at 134 RBIs for the 1895 Baltimore Orioles. He also scored more than 100 runs six times, totaling 165 for the Orioles in 1894, and batted over .300 in eleven straight seasons, from 1893 to 1903. In 1896, he stole 87 bases for the Orioles. Still, aside from leading the league once in stolen bases, he never led the circuit in any offensive category. Kelley was elected to the Hall of Fame by the Veterans Committee in 1971.

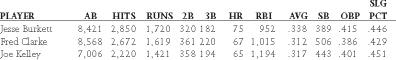

A look at the career statistics of the three men indicates that they were all fine players:

While Burkett and Clarke were basically equal as run producers, Kelley had a clear advantage there, driving in more runs in far fewer at-bats and scoring them at essentially the same rate. Burkett finished with the highest batting average and on-base percentage— both very important categories for a good leadoff hitter.

The feeling here is that all three men were decent selections by the Veterans Committee, but that none was a clear-cut Hall of Famer along the lines of an Ed Delahanty, or a few of the other outfielders from that time period whose careers we will examine shortly. Since Burkett was the only one to lead the league multiple times in any major offensive category, he should probably be viewed as the most legitimate choice of the three. But none was a dominant player, and all should be viewed as borderline Hall of Famers.

Jim O’Rourke

Nicknamed “The Orator” because he was considered to be the most eloquent player of the 19th century, Jim O’Rourke was one of the very first Hall of Famers to play in the major leagues. O’Rourke’s big league career began in 1873, with the Boston Braves, and ended 21 years later, with the original Washington Senators of the National League. In between, he had stints with the Providence Grays, Buffalo Bisons, and New York Giants.

O’Rourke was known for being a good hitter, but was also considered to be a liability in the field. He led the league in home runs, triples, runs scored, and hits once each, and in on-base percentage twice. O’Rourke’s finest season came in 1890, when, playing for the Giants, he hit nine home runs, drove in 115 runs, scored 112 more (one of five times during his career he scored more than 100 runs), and batted .360. He finished his career with 62 home runs, just under 1,200 runs batted in, just over 1,700 runs scored, slightly more than 2,600 hits, 150 triples, 461 doubles, and a .311 batting average. In his five best big league seasons, O’Rourke posted batting averages of .350, .362, .348, .347, and .360.

However, in only two of those years did he have as many as 400 at-bats. In fact, due to the infrequency with which games were played in the early years of professional baseball, O’Rourke never had more than 370 at-bats during his first ten seasons. In his entire career, he surpassed 500 at-bats only three times, and he had as many as 400 at-bats only seven other times. It is, therefore, extremely difficult to gauge his performance against that of other Hall of Fame players and ascertain whether or not he is truly qualified. The feeling here is that, while the Veterans Committee’s 1945 selection of O’Rourke was not necessarily a bad one, it was one that was questionable, especially when taking into consideration the limited amount of playing time he experienced throughout most of his career.

Heinie Manush/Chick Hafey

Both of these men had their finest seasons from the mid-1920s to the early ’30s, during one of the greatest hitting eras in the history of the game. This needs to be factored in to the equation when reviewing their Hall of Fame credentials.

Heinie Manush’s 17-year major league career included stints with the Detroit Tigers, St. Louis Browns, Washington Senators, Boston Red Sox, Brooklyn Dodgers, and Pittsburgh Pirates. Manush was neither a power-hitter nor a big producer of runs. He never hit more than 14 home runs in any season, and he knocked in more than 100 runs only twice. However, he was an outstanding line-drive hitter, batting as high as .378 on two separate occasions, and surpassing the .340-mark four other times. Manush also collected more than 200 hits four times, scored more than 100 runs six times, compiled more than 40 doubles six times, and finished in double-digits in triples eight times. He led the American League in batting in 1926 when he hit .378 for the Tigers, and he matched that figure two years later while playing for the Browns. He also led the league in hits twice, doubles twice, and triples once.

However, Manush was never considered to be among the very best players in the game, and, with the possible exceptions of the 1926 and 1928 seasons, could not even be included among the five or six best players in his own league. In addition, for most of his career, he was rated well behind Al Simmons among American League leftfielders. In other Hall of Fame criteria, he finished in the top five in the MVP voting three times, and, as was mentioned earlier, was a league-leader in various offensive categories on six different occasions. It is difficult to say whether or not Manush contributed to his team’s success in other ways because he played on teams that finished in the second division for most of his career. However, he was a member of the 1933 Washington Senators team that won the American League pennant.

Chick Hafey spent his entire 13-year career in the National League, playing eight seasons with the Cardinals and five with the Reds. Rogers Hornsby, who was a teammate of his for three seasons in St. Louis, once said that Hafey was as good a righthanded hitter as he ever saw. Hafey is said to have hit the ball as hard as any righthanded batter of that era, with the exception of Jimmie Foxx. During his career, he hit more than 20 home runs, drove in more than 100 runs, and scored more than 100 runs three times each. He also batted over .330 in five straight seasons, from 1928 to 1932, winning the N.L. batting title in 1931 with a mark of .349.