Baseball's Hall of Fame or Hall of Shame (7 page)

Nellie Fox was the best second baseman in the American League for a decade. From 1951 to 1960, there was no better second sacker in the league and, in at least three or four of those seasons, he was the best player at his position in baseball. He led the league in hits four times, batted over .300 six times, scored more than 100 runs four times, and was an outstanding fielder, leading the league six times. He was selected to the All-Star team 12 times, won the league MVP Award in 1959, and finished in the top ten in the voting five other times. A look at his numbers reveals that Fox was actually quite comparable to Schoendist offensively:

Why, then, does his resume seem to be so much more impressive than that of Schoendist? The reason lies in the fact that the two men played during an era in which the National League (Schoendist’s) was becoming the more dominant of the two. Due to the senior circuit’s greater willingness to adapt to the changing times and accept into its ranks the top black and Hispanic talent that was available, the N.L. became the stronger of the two leagues during the 1950s. Therefore, Schoendist had a more difficult time finishing among the league leaders in the various hitting categories and receiving support in the MVP voting. But, in actuality, both players were very similar.

So, what does all this mean? How should these players be viewed, and which, if any of the six belong in Cooperstown?

The feeling here is that the answer lies in the standards one sets for legitimate Hall of Famers. None of the six men—Lazzeri, Herman, Doerr, Gordon, Schoendist, or Fox—was a truly great player who should be thought of as an obvious Hall of Famer. But all six were very good players whose presence in Cooperstown is not an embarrassment to the Hall.

Johnny Evers

We saw earlier that Frank Chance was not truly deserving of a spot in Cooperstown. The same could be said for his infield mate Johnny Evers. A look at his career numbers makes one search for a plausible explanation for his election:

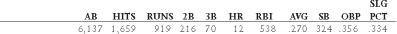

In spite of the fact that Evers played during the Deadball Era, 12 home runs, 538 runs batted in, 919 runs scored, a .270 career batting average, and a slugging percentage of .334 are not very impressive numbers. He never led the league in any major offensive category, coming the closest by finishing second in stolen bases in 1907, and second in on-base percentage in both 1908 and 1912. Evers did manage to hit .300 twice, but never knocked in more than 63 runs or scored more than 88 runs in any season. Somehow, he managed to win the National League Most Valuable Player Award in 1914 despite hitting just one home run, driving in only 40 runs, batting only .279, accumulating just 137 hits, and stealing only 12 bases for the pennant-winning Boston Braves.

One would think that the explanation for Evers’ election must be rooted in the fact that he was such a great defensive player. Yet, during his career, he led National League second basemen in fielding just once, and the “great” double-play combination of

Tinker-to-Evers-to-Chance

led the league in double-plays just once. It is quite apparent, then, that just as his teammate Frank Chance made it in on the heals of the effusive praise doled out by that frustrated New York sportswriter, Evers’ election too was based more on rhetoric than on performance.

Bill Mazeroski

In a letter to

The Sporting News

, which appeared in the July 21, 1986 issue, Thomas A. Morgan of Oakville, Connecticut wrote: “It is already absurd the number of less-than-fantastic players who have gone to Cooperstown. Let’s not get totally ridiculous over players who excelled in one or two areas and were less than mediocre in all others…”

One would think that Mr. Morgan had Bill Mazeroski in mind when he wrote this letter. Mazeroski turned two on the double-play better than any other second baseman in baseball history, but, other than that, he was a very mediocre player. Putting him in the Hall of Fame is equivalent to admitting Carl Furillo because he had perhaps the strongest throwing arm of any outfielder in baseball history, or Jim Sundberg because he was as good behind the plate as any catcher has been, or Vince Coleman because he was a great base-stealer.

No player should be elected to the Hall of Fame because he

excelled in one area, if he was mediocre in all others.

Some might argue that Lou Brock and Rickey Henderson were elected primarily on the strength of their abilities as base-stealers. However, both men were far more than just base-stealers, excelling in other areas as well. Brock was a .293 lifetime hitter who finished his career with more than 3,000 hits and 1,600 runs scored. In addition, he helped change the way the game was played with his thievery on the base-paths. Henderson was the greatest leadoff hitter the game has ever seen. In addition to being the all-time base-stealing king, he is the all-time leader in runs scored, and he compiled a lifetime .401 on-base percentage and more than 3,000 hits.

Bill Mazeroski, on the other hand, was a below-average offensive player, even for a second baseman. Here are his career numbers:

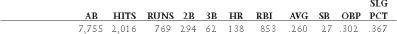

Mazeroski never came close to leading the league in any offensive category. The best he could do was finish in the top 10 three times in triples. In 17 seasons, he scored only 769 runs and batted .260, and his career on-base percentage was a poor .302. That last mark was the result of his lack of patience at the plate, since he never walked more than 40 times in any season. Mazeroski never hit any higher than .283, and he never scored more than 71 runs in a season. In addition, he did not fare particularly well in the MVP balloting, placing in the top 10 only once, in 1958, when he finished in eighth place.

Mazeroski was selected to the N.L. All-Star team seven times— from 1958 to 1960, from 1962 to 1964, and again in 1967. However, in only one of those seasons, 1958, could he have been legitimately referred to as the best second baseman in baseball. Nellie Fox was the top second baseman in 1959-60, Bobby Richardson was number one from 1962-64, and Rod Carew was tops in 1967.

There are some who would argue that Brooks Robinson and Ozzie Smith were elected to the Hall of Fame primarily for their defense. While this is true, both players were also above-average offensive players, and they fared much better than Mazeroski in the annual MVP and All-Star voting.

Robinson hit 268 career home runs, accumulated more than 2,800 hits, and scored more than 1,200 runs. He was also an excellent clutch performer, with 1,357 career runs batted in and a .303 lifetime postseason batting average. In addition, he was voted the American League’s Most Valuable Player in 1964, finished in the top five on four other occasions, and was selected to the All-Star Team 15 straight seasons at one point.

While Smith struggled at the plate in his first few seasons, he eventually turned himself into a solid offensive player, finishing his career with 2,460 hits, 1,257 runs scored, and 580 stolen bases. Like Robinson, he was a perennial All-Star.

In addition, both Robinson and Smith were clearly the greatest defensive players at their positions in baseball history. While many have said the same thing about Mazeroski, that is actually quite debatable. Though he is undoubtedly somewhat prejudiced, Tim McCarver has said that, as good a defensive player as Mazeroski was, his former Cardinals teammate Julian Javier was the best fielding second baseman he ever saw. While he may have been the best at turning the double-play, it is also difficult to imagine Mazeroski being a better all-around second baseman than either Roberto Alomar, Ryne Sandberg or Bobby Grich. Alomar was more acrobatic and had more range than Mazeroski. Sandberg is the all-time leader in fielding average among major league second basemen, with a mark of .990 (seven points higher than Mazeroski), and also holds N.L. records for second basemen by playing 123 consecutive games and accepting 582 chances without making an error. In two different seasons, Mazeroski made as many as 23 errors, quite a substantial number for a second baseman. Grich was also an exceptional fielder who finished his career with the same fielding average as Mazeroski.

Aside from being outstanding fielders, another thing that Alomar, Sandberg and Grich had in common was that they were all much, much better offensive players than Mazeroski. Having played from 1970 to 1986, Grich was the closest contemporary of the three to Mazeroski. Let’s take a look at the career numbers of both players alongside one another:

Note that, in almost 1,000 fewer at-bats, Grich finished well ahead of Mazeroski in almost every offensive category. In particular, notice the difference in the number of runs scored and home runs, and the discrepancy in their on-base and slugging percentages. In addition, Grich once led the American League in home runs and, in another season, hit 30 homers, knocked in 101 runs, and batted .294. Even if a slight edge on defense is conceded to Mazeroski, it is quite apparent that Bobby Grich was a far better all-around player. Yet, Mazeroski is in the Hall of Fame and Grich is not.

Why?

The answer lies in the fact that the former had friends on the Veterans Committee that elected him in 2001. One of the members of the Committee, in particular, had strong ties to Mazeroski. That would be Joe Brown, former Pirates executive during Mazeroski’s playing career in Pittsburgh.

In his book on the Hall of Fame, published in 1994, before Mazeroski’s election, Bill James writes: “I’d like to see Mazeroski in the Hall of Fame because I’m a Royals fan and the selection of Mazeroski would greatly strengthen the argument for Frank White…” He then goes on to compare both the offensive and defensive career statistics for both players to provide evidence of what truly comparable players they were. He is right; they

were

truly comparable players. However, his argument is a perfect illustration of why players like Bill Mazeroski should never be elected to the Hall of Fame. They lower the standards for all the other players, and lessen the credibility of those making the selections.