Baseball's Hall of Fame or Hall of Shame (2 page)

SELECTION PROCESS AND ELIGIBILITY

SELECTION PROCESS AND ELIGIBILITY

There are several flaws in the selection process employed over the years to determine which players are most deserving of enshrinement at Cooperstown. Many of these defects will be touched on in later chapters. The one that will be mentioned here, though, is baseball’s inability to change with the times. The BBWAA’s initial assignment of conducting the elections back in 1936 seemed quite reasonable at the time. There was no television, most games were not broadcast over the radio, and the number of baseball publications and magazines were few and far between. Aside from former players, managers, and coaches, the baseball writers seemed to be the most knowledgeable people, and the most logical ones to be entrusted with making the selections. They represented the only true form of sports media in this country at that time.

However, as we all know, radio and television broadcasting of baseball games has grown dramatically over the past several decades. Specialized TV stations such as ESPN, that not only broadcast games, but show highlights on a nightly basis, and publications such as

The Sporting News

and

Sports Illustrated

, have become commonplace. Clearly, the baseball writers no longer hold a monopoly on the media frenzy surrounding the sport, and they are no longer the only people who are qualified to vote in the Hall of Fame elections. Yet they continue to be the only ones involved in the process. This system excludes others who are not only qualified to take part in the elections, but who, in many instances, are more qualified than the writers. It also works under the incorrect assumption that the writers, who usually come into closer contact with the players over the course of the season than do other members of the media, can put aside their own personal feelings and biases towards the players and base their selections strictly on performance and on-the-field achievements. As we have seen over the years, that is not always the case.

There are several examples of this. One would be Juan Marichal, who, with the exception of Sandy Koufax, was as great a pitcher as anyone during the 1960s. Yet, due to an unfortunate incident that occurred in a 1965 game between his San Francisco Giants and the archrival Los Angeles Dodgers in which he hit Dodger catcher John Roseboro over the head with a bat, Marichal had to wait until his third year of eligibility to be voted into Cooperstown. Meanwhile, contemporaries Bob Gibson, Tom Seaver, Jim Palmer, and later, Nolan Ryan, none of whom, with the possible exception of Gibson, was a better pitcher than Marichal, all made it in on the first try.

Another example would be Jim Rice. The former Boston Red Sox outfielder was far more of a borderline Hall of Fame candidate than Marichal, but his credentials were actually quite similar to those of media favorite Kirby Puckett, who was elected the first time his name appeared on the ballot. Rice, who shared a somewhat contentious relationship with the writers throughout his career, finally gained admittance in his last year of eligibility.

In addition, although his case could not be directly related to the Hall of Fame voting, Ted Williams’ lack of popularity with the press would be another prime example of bias on the part of writers. The Red Sox great once lost an MVP vote by one point because one of the Boston sportswriters (the aforementioned Mel Webb) didn’t give him as much as a tenth-place vote on his ballot.

It, therefore, seems quite clear that granting sole responsibility to one body of people during the selection process can be a dangerous thing, and that it can often lead to inaccuracies and injustices. Nevertheless, a system has evolved through the years that provides players with two means of getting into the Hall of Fame. Essentially, that system is the following:

• A player can be elected by either the Baseball Writers Association of America or by the Hall of Fame Veterans Committee.

• A player becomes eligible five years after he retires, if he plays at least ten seasons in the Major Leagues.

• To be selected for the Hall of Fame, a player must be named on at least 75 percent of the BBWAA ballots.

• A player becomes ineligible for election by the BBWAA if he has not been selected in the first fifteen years that his name has been on the ballot.

• Those who are not selected in their fifteen years of BBWAA eligibility are ineligible for five years following.

• After five years, those players rejected by the BBWAA become eligible to be elected by the Hall of Fame Veterans Committee.

• The old 15-member Veterans Committee, which was comprised of veteran players, managers, and/or baseball executives, was replaced in 2003 by a group comprised of the living members of the Baseball Hall of Fame (60), living recipients of the J.G. Taylor Spink Award (12), living recipients of the Ford C. Frick Award (13), and the old Veterans Committee members whose terms had yet to expire (3). This group of 90 increased the size of the old committee six-fold.

• The Hall of Fame Veterans Committee also requires a 75 percent vote to elect anyone.

• Beginning in 2003, the Veterans Committee began holding its election of players every other year. Also beginning in 2003, the election of managers, umpires, and executives by the Veterans Committee now occurs every four years.

The rules governing the elections state that, “Candidates shall be chosen on the basis of playing ability, integrity, sportsmanship, character, and their contribution to the team, or teams, on which they played—as well as to baseball in general.”

As we shall see later, these rules have not always been strictly adhered to, and much liberty has been taken in their interpretation.

There has always been at least one other selection committee involved in the Hall of Fame election process to augment the selections made by the BBWAA. Over the years, the composition and function of this committee has changed, but it has always managed to make its presence felt.

First, there was the original Old-Timers Committee, which couldn’t agree on anything, never elected anyone to the Hall, and was disassembled prior to 1937. Then, there was the Centennial Commission of 1937 and 1938, headed by Judge Landis. As we saw earlier, this group chose not to elect any nineteenth century players, but, rather, the people who were most influential in getting them elected to office.

After this Centennial Commission was pared down and retooled, its name was changed back to the Old-Timers Committee in 1939, and, for more than a dozen years, this group’s primary function was selecting players whose careers spanned parts of the nineteenth century, or the first decade of the twentieth. Unfortunately, as we also saw, this committee did irreparable damage to the Hall by electing many players with questionable credentials, permanently lowering its standards. This committee was replaced by the first Veterans Committee in 1953, whose responsibility was to select the old-time players previously passed on by the BBWAA and no longer eligible to be voted in by them. Its members were also to elect any former managers, umpires, or executives who they deemed worthy of induction. This group was comprised of former players, managers, executives and members of the media who had been around the game for many, many years. Although the members of this committee periodically changed, it is particularly noteworthy because this Veterans Committee continued to function for the next 50 years.

We will go into more detail about this group shortly, after we discuss the final special selection committee empowered with inducting players into the Hall of Fame.

That final group was the Negro Leagues Committee of 1971-1977. Appointed by then-commissioner Bowie Kuhn to evaluate Negro League stars, this group was comprised of five former players (Eppie Barnes, Roy Campanella, Monte Irvin, Judy Johnson, Bill Yancey), three former executives or promoters (Frank Forbes, Ed Gottlieb, and Alex Pompez), and two writers (Sam Lacy and Wendell Smith). After it was announced early in 1971 that former pitching great Satchel Paige was the first former Negro League star to be inducted into the Hall of Fame, this committee met annually for the next seven years and elected eight other former Negro League players to the Hall: Josh Gibson and Buck Leonard in 1972, Monte Irvin in 1973, Cool Papa Bell in 1974, Judy Johnson in 1975, Oscar Charleston in 1976, and John Henry “Pop” Lloyd and Martin Dihigo in 1977. After their 1977 meeting, the committee voted to disband, informing the Hall of Fame that their assignment was completed. The committee was discontinued, and the power to select Negro League players was transferred to the “Veterans Committee.” Several more players from the Negro Leagues were eventually inducted, more than doubling the total number of former Negro League stars in the Hall of Fame.

Now, back to the Veterans Committee, which had its roots in the original Old-Timers Committee. In all fairness, the members of the Old-Timers Committee cannot be faulted

too

heavily for their selection of several turn-of-the century players who were not truly worthy of induction, because they did not have available to them the plethora of statistics that have since been uncovered. In the early years, organized baseball did not maintain career records. There was no

Baseball Encyclopedia

or

Total Baseball

that these men could use as a point of reference. They had to base their opinions mostly on what they had either seen for themselves, read in the newspapers, or been told by other people. Until men like Ernest Lanigan came along, the outstanding baseball statistician of his time who was hired as the Historian of the Hall of Fame in 1948, baseball statistics were hard to come by. Lanigan collected box scores and accounts of games, studied and analyzed them, and wrote articles about them. Before Lanigan came along, career records were practically non-existent.

When Lanigan retired in November of 1958, he was replaced in early 1959 as the Hall of Fame’s Historian by Lee Allen. Allen, like Lanigan, was fascinated with statistics and began looking into all the research materials that the Hall had accumulated over the years, putting it into the form of a library. He was perhaps the game’s first true historian. Eventually, Allen came to serve as an advisor to the members of the Veterans Committee, preparing background material on the players being considered for election—clippings, statistics, and other personal material. With this background information now available to them, the committee members were able to make more informed decisions and, for the most part, do a better job of electing the most-deserving players. There are, however, always exceptions, and these exceptions are all too often rooted in favoritism.

Frankie Frisch was a Hall of Fame second baseman who played for the New York Giants from 1920 to 1926, and for the St. Louis Cardinals from 1927 to 1937. He was also a player-manager for the Cardinals for several years, and was known for being a team leader, having a fiery personality, being somewhat intimidating, and yet also being well liked. Frisch felt that the players of his day were superior to the more modern players, and he made no attempt to conceal that opinion to others. He was named to the Veterans Committee in 1967 and was joined four years later by his former Giants teammate Bill Terry, also a former player-manager, and another man known for being a leader. Over the next few seasons, Frisch and Terry embarked on getting as many of their former teammates elected as possible. This would not have been a bad thing if they were truly deserving of induction, but, in most instances, that was not the case. Enshrined in Cooperstown, largely as a result of Frisch’s and Terry’s prodding, were:

Jesse Haines

—a good pitcher on Frisch’s Cardinals teams.

Dave Bancroft

—the Giants’ shortstop and Frisch’s double play partner for four years.

Chick Hafey

—a hard-hitting outfielder and Frisch’s teammate on the Cardinals for five seasons.

Ross Youngs

—a good-hitting outfielder with little power who played with Frisch on the Giants for seven seasons.

George “High-Pockets” Kelly

—a power-hitting, good-fielding first baseman who played alongside Frisch in the Giants’ infield for seven seasons.

Jim Bottomley

—St. Louis Cardinals first baseman from 1922 to 1932 and Frisch’s teammate for six seasons.

Fred Lindstrom

—Giants third baseman from 1924 to 1932, a teammate of Frisch for three seasons, and of Terry for all nine of those years.

Of these seven players, only Bottomley was a legitimate Hall of Famer. Lindstrom and, perhaps, Bancroft could be described as marginal candidates, but the other four men were undeserving. The careers of Kelly, Youngs, and Hafey were all too short and not productive enough, and Haines simply wasn’t good enough. We will take a closer look at each of these players later, but it seems clear that the selections of the members on the Veterans Committee have often been based on more than just playing ability.

This revised Veterans Committee served for 50 years, from 1953 to 2002 and in 2003, it was replaced by a group comprised of the living members of the Baseball Hall of Fame, the living recipients of the J.G. Taylor Spink Award, the living recipients of the Ford C. Frick Award, and the remaining Veterans Committee members whose terms had not yet expired. This realignment should help to minimize the number of elections based on bias and eliminate some of the peer pressure that previously existed whenever the committee got together. This reconfiguration was most likely prompted by the general feeling that the Hall of Fame standards had become too low, and that too many players had already been elected who were not truly deserving. In particular, there were many who objected to the election of former Pirates second baseman Bill Mazeroski in 2001, one of the worst choices in the history of the Hall of Fame voting. Hopefully, this revamped committee will do a better job.

One of the major problems that has always made voting for potential Hall of Famers so difficult is that it has never been clearly defined what constitutes a legitimate Hall of Famer. While certain statistical standards have been used to attempt to identify qualified candidates, much of the selection process is subjective, since each person looks for different things and has a different idea of what qualifies a player to be elected. Certain benchmarks have been used to identify worthy candidates. Thus far, all eligible players who accumulated either 500 home runs (with the exception of Mark McGwire) or 3,000 hits during their careers have made it into Cooperstown. So, too, have all pitchers with 300 or more wins. But the majority of players who have been elected did not reach any of these milestones, so, obviously, other criteria are being used as well

The first question that needs to be asked is this: Should 500 home runs, 3,000 hits, or 300 victories guarantee election? While most people would most likely answer in the affirmative, I am somewhat hesitant to do so. While accumulating 3,000 hits or 300 wins is certainly an outstanding achievement that signifies a certain level of consistency that few have attained, it is possible to reach either plateau more because of longevity than because of greatness. In particular, this applies to the attainment of 300 victories. All one needs to do is look at the careers of pitchers such as Don Sutton and Phil Niekro. Both men were fine pitchers who had long and successful careers. But neither man was ever thought of as being a

great

pitcher, even at his very best. It is also possible to win in excess of 300 games, but also to lose close to 300 games, as both Niekro and Nolan Ryan did. Thus, while reaching such milestones certainly goes a long way towards qualifying a player for Hall of Fame election, one still needs to examine the player’s entire career before blindly admitting him.

In the case of 500 career home runs, that is a benchmark that may have to reevaluated going forward since it no longer carries the same significance it once did. Prior to 1990, it was commonplace for a player to lead his league in home runs with a total that approximated 40. Hitting 50 homers in a season was considered to be quite an achievement. However, players have compiled more than 40 home runs in a season with great regularity over the past two decades. Furthermore, it was not at all uncommon during the Steroid Era that lasted from the 1990s to the turn of the century for the league leader to finish with a total somewhere between 50 and 60 long balls. It follows that, in future seasons, more players will likely be reaching the 500 home run plateau. It may well be that the bar needs to be raised to 600 homers when considering future generations of sluggers for Hall of Fame induction. After all, the Hall is supposed to be reserved only for those players who exhibited exceptional performance during their careers. If the attainment of 500 home runs becomes a more common occurrence, can it honestly be said that any player who reaches that milestone accomplished something truly exceptional? A player must be judged within the context of the era in which he played, and his numbers must stand out among those of the other players of his era.

Along those lines, what seems like a very high career batting average should not automatically guarantee induction either. During the 1920s and 1930s, known for being a hitter’s era, it was not at all uncommon for players to lead the league in batting with marks approaching, or even exceeding .400. In fact, in every season from 1920 to 1925, at least one player in the major leagues surpassed the .400 mark. Team batting averages routinely approached .300, particularly during the ’20s and early ’30s. More players during this period finished with career batting averages well above the .300 mark than in any other era in baseball history.

Were the players of this period better, or did the rules of the game employed at that particular time simply favor the hitters? One would tend to think the latter. Yet more hitters who played during this period were inducted into the Hall of Fame than from any other era. While players such as Earle Combs, Heinie Manush, Chick Hafey, Fred Lindstrom, and Ross Youngs were all good players who finished with career batting averages well above .300, were they truly exceptional enough to be deserving of Hall of Fame status? That is something this book will attempt to ascertain by judging these men within the context of the era in which they played.

The question then follows: If statistics by themselves are not the determining factor, how can you truly tell if a player excelled enough during his respective era to be worthy of induction into the Hall? To answer that question, I came up with a list of eight other questions. Some of these questions are actually quite similar in nature to those asked by Bill James in his book,

Whatever

Happened To The Hall Of Fame? Baseball, Cooperstown, and the

Politics of Glory,

a work that will be referred to more than once throughout this book. At the root of each question is an attempt to uncover just how dominant a player was during the time in which he played, since the feeling here is that a certain level of dominance must have been achieved in order for a player to be Hall of Fame worthy.

The chart indicates the questions that need to be asked:

Hall of Fame Questions

1. In his prime, was the player ever considered to be, for at least three years, either the best player in baseball or the best player in his league?

2. For the better part of a decade, was the player considered to be among the five or six best players in baseball?

3. Could a valid case be made for the player being one of the ten best players at his position in baseball history?

4. For the better part of a decade, was the player considered to be the best player in the game at his position? In his league?

5. How did the player fare in the annual voting for the MVP or Cy Young Award? Did he ever win either award? If not, how often did he finish in the top 10?

6. How often was the player selected to the All-Star team?

7. How often did the player lead his league in some major offensive or pitching statistical category?

8. Was the player a major contributor to his team’s success? Did he do the little things to help his team win? Did he play mostly on winning teams? Was he a team leader? Was he a good defensive player? Is there any evidence to suggest that the player was significantly better or worse than is suggested by his statistics?

The answers to these questions will go a long way in determining a player’s Hall of Fame legitimacy, and some will carry more weight than others. For example, if the answer to the third question is “yes,” and a legitimate case could be made for the player being one of the greatest ever at his position, this by itself should be enough to legitimize his place in Cooperstown. If questions one, two, and four can be answered in the affirmative, the chances are pretty good that the player deserves to be in the Hall of Fame. There are, however, exceptions. One can look at players such as Don Mattingly and Dave Parker for examples. Both Mattingly and Parker were thought of as being arguably the best player in the game at one point. For five or six years, each man was considered to be among the top five players in the game, and, quite possibly, the best player at his respective position (Parker, from 1975 to 1979; and Mattingly, from 1984 to 1988). Each player also did relatively well in the other areas. Each won an MVP Award; each made the All-Star team several times; each led his league in various hitting categories. But, in each case, the player’s dominant level of play lasted only a few years (in Mattingly’s case, because of back problems; in Parker’s case, because of drug and weight-related problems) and, as a result, neither man is in the Hall of Fame. Therefore, other things need to be considered, along with the answers to these questions.

If questions five through eight can be answered in the affirmative, the player is doing well. However, he probably needs to get a positive response to at least one of the other four questions to legitimize his place in Cooperstown.

Of course, the concept of using these questions as the primary criterion is not without its flaws. For one thing, prior to 1932, there were many seasons in which one or both major leagues did not present an award for its Most Valuable Player. Also, prior to 1956, no Cy Young Award was presented annually, and from 1956 to 1966, only one was given out to the best pitcher in both leagues combined. In addition, the first All-Star game was played in 1933, so All-Star appearances cannot be used as a reference prior to that.

Finally, there is the case of the stars from the old Negro Leagues. Due to the limited availability of statistical data and information in general surrounding their careers, the answers to many of the above questions are unattainable. With these players, most of what is known about them comes from the things others who saw them play have said. We will have to assume that the panel of experts on the Negro Leagues Committee of 1971-1977, as well as the members of the Veterans Committee who later elected several other stars from these leagues, knew what they were doing. The pieces of information that I have been able to uncover about these players through research seem to indicate that the committee members did a good job. This will be discussed at greater length in future chapters.

Keeping all this in mind, we are now ready to take a look at each member of the Hall of Fame, examine his credentials, and determine whether or not he truly belongs in Cooperstown. The format that will be used is a relatively simple one:

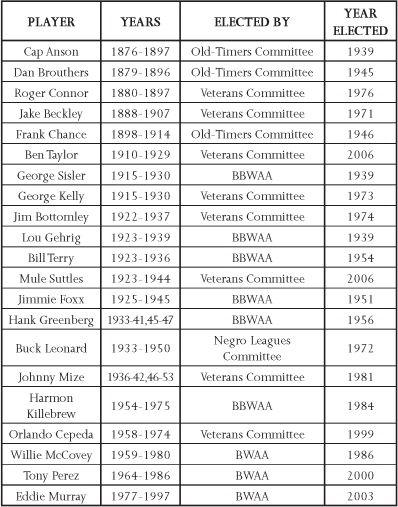

1. The players at each position who have been elected to the Hall of Fame will be listed in chronological order based on the years that they played.

2. The years that the players’ careers spanned, the manner in which they were elected, and the year in which they were elected will also be listed.

3. A summary of each player’s credentials will be provided, as well as a discussion of the legitimacy of his selection, or lack thereof. The player summaries for each position will start with the most valid selections, and end with the most questionable.

Lou Gehrig/Jimmie Foxx

As the two greatest first basemen in baseball history, both Gehrig and Foxx are most deserving of their places in Cooperstown.

Lou Gehrig’s 493 home runs, 1,995 runs batted in, .340 career batting average, 1,888 runs scored, .447 career on-base percentage, and .632 slugging percentage all place him high on the all-time lists. He is also the career leader in grand-slams (23), and he led his league in home runs three times, RBIs five times, and batting average once, winning the American League triple crown in 1934 (49 HR, 165 RBIs, .363 AVG), and the league’s MVP Award twice. He was selected to six American League All-Star teams, even though the game was not played until his eighth full season in the league. Gehrig was also selected to

The Sporting

News’

All-Star team six times, and was the best first baseman in baseball for much of his career. He was clearly the best in the major leagues at his position in 1927, 1928, 1931, 1934, and 1936 (he hit more than 45 home runs, knocked in more than 150 runs, and batted over .350 in four of those seasons). He also vied with the National League’s Bill Terry for that honor in 1930 (41 HR, 174 RBIs, .379 AVG), and with the American League’s Hank Greenberg in 1937 (37 HR, 159 RBIs, .351 AVG). Gehrig was among the top five players in the game from 1927 to 1937, and was arguably its best player in 1927, 1931, 1934, and 1936. In most opinion polls, he has been selected as the game’s greatest all-time first baseman, and he is generally considered to be one of the five or ten greatest players in the history of the game.

Jimmie Foxx’s resume is almost as impressive as Gehrig’s. He had 534 home runs, 1,922 RBIs, a .325 career batting average, 1,751 runs scored, a .428 on-base percentage, and a .609 slugging percentage. He won four home run crowns, three RBI titles, and led the league in batting twice. Like Gehrig, he won a triple crown, capturing his in 1933, when he hit 48 home runs, drove in 163 runs, and batted .356 for the Philadelphia Athletics. Foxx was the first player in either league to win the MVP Award three times, and was also the first player to hit more than 50 home runs with two different teams, slugging 58 for the Athletics in 1932, and smashing another 50 for the Boston Red Sox in 1938. Foxx was the best first baseman in baseball in 1932, 1933, 1938, and 1939, and was selected to the American League All-Star team in each season, from 1933 to 1940. He was among the top five players in the game from 1929 to 1940, surpassing 30 home runs and 100 RBIs in each of those 12 seasons. He was also the very best player in the game in each of his three MVP seasons—1932, 1933, and 1938. Although he is not as well-remembered as Gehrig, Foxx was one of the most prolific sluggers the game has ever seen, and deserves to be ranked somewhere in the top ten players of all-time.

George Sisler/Hank Greenberg

Although neither Sisler nor Greenberg was quite on the same level as Gehrig and Foxx, they were both great players who clearly earned their places in Cooperstown.

George Sisler was generally considered to be one of the finest all-around players of his era. An excellent baserunner and the finest fielding first baseman of his day, he finished his career with a .340 batting average and 375 stolen bases. Sisler won two batting titles, hitting .407 in 1920, and compiling a .420 batting average in 1922, while capturing league MVP honors. His 257 hits in 1920 stood as the major league record for 84 years, until Ichiro Suzuki collected 262 safeties in 2004. From 1920 to 1922, Sisler was one of the two or three best players in the game, and, from 1917 to 1922, he was clearly the best first baseman in baseball. Over that six-year stretch, he batted no lower than .341, surpassed the century mark in both RBIs and runs scored three times each, and stole at least 35 bases five times. Sisler was arguably one of the five greatest players at his position in baseball history, and many who saw him play, including Ty Cobb, considered him to be as fine an all-around player as they ever saw.

Hank Greenberg missed almost five full seasons in the prime of his career to military service, yet still managed to hit 331 home runs, drive in 1,276 runs, win two MVP Awards, and help lead his Detroit Tigers to four pennants and two world championships. He led the American League in home runs and runs batted in four times each, once hitting 58 homers, challenging Babe Ruth’s record of 60, and once driving in 183 runs, challenging Lou Gehrig’s A.L. single-season record of 184. He is also tied with Gehrig for the highest RBI per-game ratio since 1900, with a mark of .92.

Greenberg was one of the five or six best players in the game from 1935 to 1940, during which time he vied with Lou Gehrig and Jimmie Foxx for first base supremacy in the major leagues. He was arguably the very best player in the game in 1935, 1937, and 1940. In the first of those seasons, Greenberg led the majors in home runs (36) and runs batted in (170), while batting .328, scoring 121 runs, and finishing with 16 triples, 46 doubles, and 203 hits in winning A.L. MVP honors. In 1937, he hit 40 homers, led the majors with 183 runs batted in, batted .337, scored 137 runs, and collected 14 triples, 49 doubles, and 200 base hits. In 1940, Greenberg won his second MVP Award by leading the league in home runs (41) and runs batted in (150), batting .340, and scoring 129 runs. In just nine full major league seasons, Greenberg finished in the top ten in the league MVP balloting six times. Despite the relative brevity of his career, Greenberg may well have been one of the five greatest first basemen in baseball history.

Eddie Murray

Although he has never fully received the credit he deserves for having been one of the greatest first basemen ever to play the game, Eddie Murray was just that. In fact, while Mark McGwire was more popular with the press and the fans, Murray was arguably the finest all-around first baseman of the last half of the 20th century. McGwire, Harmon Killebrew, and Willie McCovey all hit more home runs over the course of their careers, but none was as consistent as Murray as a run-producer, hit for as high an average, or was as good defensively. Rafael Palmeiro also hit more home runs than Murray, was extremely consistent, and hit for a comparable average. However, his numbers were inflated by both the era and the ballparks in which he played, and a huge cloud hangs over his accomplishments due to his involvement with steroids.

Murray ended his career with 504 home runs, 1,917 runs batted in, 1,627 runs scored, a .287 batting average, and 19 grand slams—good enough for third on the all-time list. He also won three Gold Glove Awards.

Murray was a model of consistency, averaging 28 home runs and 99 runs batted in a year from 1977 to 1988. During that period, he hit more than 30 homers, knocked in more than 100 runs, and batted over .300 five times each. His best years were 1980 to 1985, a period during which he hit at least 29 home runs and bettered the 100-RBI mark in all but the strike-shortened 1981 season. He also batted over .300 four times during that stretch, with his finest seasons coming in 1983 and 1985. In the first of those years, Murray hit 33 home runs, knocked in 111 runs, batted .306, and finished runner-up to teammate Cal Ripken Jr. in the league MVP voting. Two years later, he hit 31 homers, knocked in a career-high 124 runs, and batted .297. For those six seasons, Murray was one of the top two or three players in the American League, and one of the five best in baseball. He was clearly the best first baseman in the game from 1980 to 1983, and vied with Don Mattingly for that title in 1984.

During his career, Murray finished in the top ten in the MVP voting ten times, making it into the top five on five separate occasions. He was selected to the All-Star team eight times and led the American League in home runs and runs batted in once each. In addition, although Murray’s contributions off the field have never been well publicized, he contributed to his team’s success with more than just his playing ability. Cal Ripken Jr. has identified Murray as being the player who, perhaps more than anyone else, influenced him in a positive way early in his career. A valid case could also be made for Murray having been one of the five greatest first basemen in baseball history. That, in itself, justifies his place in Cooperstown.

Buck Leonard

As one of the very first Negro League players selected by the Negro Leagues Committee for induction into the Hall of Fame, Buck Leonard was clearly held in high esteem by those who were fortunate enough to have seen him play. The greatest first baseman in Negro League history, the lefthanded hitting Leonard was often compared to Lou Gehrig as a hitter, and to George Sisler as a fielder. Playing for the Homestead Grays team that won nine consecutive Negro National League titles from 1937 to 1945, Leonard was a two-time NNL home run champion and a three-time batting champion, twice topping the .395-mark. He usually hit fourth for the Grays, providing protection in the batting order for Josh Gibson, who batted third. The powerfully built Leonard was one of the Negro Leagues’ most feared hitters. Roy Campanella, who competed against him during the second half of Leonard’s career, discussed the first baseman’s hitting prowess: “He (Leonard) had a real quick bat, and you couldn’t get a fastball by him. He was strictly a pull hitter with tremendous power.” Leonard is looked upon by most black baseball experts as having been one of the five greatest players in Negro League history.

Bill Terry

Bill Terry was the finest first baseman in the National League from 1929 to 1934, and, perhaps, the best in baseball in both 1929 and 1930. In the first of those seasons, he hit 14 home runs, knocked in 117 runs, batted .372, scored 103 runs, and collected 226 hits. The following season, Terry became the last N.L. player to hit .400 when he batted .401, hit 23 homers, drove in 129 runs, scored 139 others, and set a league record by collecting 254 base hits. He had another great year in 1932, when he hit 28 home runs, knocked in 117 runs, batted .350, scored 124 runs, and finished with 225 hits. From 1929 to 1934, Terry was also among the five best players in the National League, topping the .340-mark, scoring more than 100 runs, and collecting more than 200 hits each in five of those seasons. During his career, Terry knocked in more than 100 runs six times, scored more than 100 runs seven times, and finished with more than 200 hits six times. His .341 career average ranks among the all-time best, and he was considered to be the finest defensive first baseman in the National League during the time in which he played. Terry was arguably one of the ten best first basemen in baseball history, and one of the two or three best ever to play in the National League.

Dan Brouthers/Roger Connor/Cap Anson

These three men were, by far, the greatest first basemen of the 19th century.

Dan Brouthers was probably the game’s greatest all-around hitter of his time. He led the league in batting five times, finishing his career with a mark of .342, and was a league leader in every major batting department at one time or another. In a day when knocking in 100 runs was considered to be quite an achievement, Brouthers accomplished the feat five times, twice driving in more than 120 runs. He also scored more than 100 runs eight times, reaching a career-high 153 runs scored in 1887 for the Detroit Wolverines, and topping 130 on two other occasions. Brouthers batted .350 or better six times during his career, finished in double-digits in home runs three times, finished with more than 10 triples eleven times, and stole more than 20 bases eight times. In virtually every season from 1882 to 1892, he was among the two or three best players in the game, and the sport’s top first baseman.

Although most people are probably not aware of it, it was Roger Connor’s career home run record that Babe Ruth shattered when he became the game’s dominant slugger during the 1920s. Prior to the Babe bursting onto the scene, Connor’s career mark of 138 home runs had stood for almost 25 years. Six times, Connor finished in double-digits in homers, hitting as many as 17 for the New York Giants in 1887. However, Connor did more than just hit home runs. He finished his career with 233 triples, a .317 batting average, and was the only player before 1900 to collect more than 1,000 walks. Connor knocked in more than 100 runs four times, scored more than 100 runs eight times, batted over .300 eleven times, topping the .350-mark three times, and finished in double-digits in triples eleven times, three times tallying more than 20 three-baggers.