Baseball's Hall of Fame or Hall of Shame (6 page)

Although never considered to be more than a mediocre fielder, Molitor had several seasons in which he was among the best all-around offensive players in baseball. Perhaps his two best years came in 1987 and 1993. Playing for the Milwaukee Brewers in 1987, Molitor hit a career-high .353, while scoring 114 runs and stealing 45 bases. With the Toronto Blue Jays in 1993, he batted .332, while hitting 22 homers, knocking in 111 runs, scoring 121 others, and compiling 211 base hits.

Since he was not a particularly strong defensive player who served primarily as a designated hitter for a good portion of his career, it would be difficult to classify Molitor as an exceptional all-around player. However, he was a terrific offensive player who clearly earned his place in Cooperstown.

Bid McPhee

As arguably the finest second baseman of the 19th century, Bid McPhee would have to be considered a legitimate Hall of Famer. McPhee’s career with the Cincinnati Reds began in 1882 and ended in 1899. He, therefore, spent most of his time facing pitchers who stood less than 60 feet, 6 inches from home plate. As a result, McPhee’s lifetime batting average was a decidedly mediocre .271. However, even though he batted over .300 only three times, McPhee still managed to compile a career .355 on-base percentage, finish in double-digits in triples nine times, score more than 100 runs in a season ten different times, and steal more than 40 bases seven times, compiling a career-best 95 thefts in 1887. During his career, McPhee scored a total of 1,678 runs and finished with 188 triples and 2,250 base hits. In addition, he led the league’s second basemen in fielding on eight different occasions.

Frank Grant

Rivaling Bid McPhee as the 19th century’s best second baseman was Ulysses “Frank” Grant, who played for numerous teams during his 18 years in baseball. The 5'7", 155-pound Grant began his career with Buffalo of the International League in 1886. Grant remained with Buffalo until the conclusion of the 1888 campaign, thereby becoming the first black man to play on the same team in organized ball, albeit at the minor league level, for three consecutive seasons. However, prior to the start of the 1889 season, organized ball instituted its ban on black players, relegating Grant to a nomadic existence for the remainder of his career. He spent the next decade playing with some of the top black clubs of the era, including the Cuban Giants, New York Gorhams, and Philadelphia Giants.

Grant was a consistent .300 hitter with power, an excellent baserunner, and an outstanding fielder. His strong arm and quickness in the field prompted others to compare him favorably to Fred Dunlap, the best-fielding white second baseman of the 1880s. During Grant’s days in the International League, one Buffalo writer called him the best all-around player ever to take the field for the team, even though four future Hall of Famers previously played for Buffalo.

Thus, it would seem that Grant’s 2006 induction into the Hall of Fame by the Veteran’s Committee was long overdue. However, it must be considered that he played prior to the formation of the Negro Leagues at the beginning of the 20th century. Therefore, even though Grant played for some of the top black teams of the era, he competed in leagues that were not very well organized, and whose level of competition is a mystery to even the most knowledgeable baseball historians. Furthermore, the paucity of available statistics surrounding his career makes it extremely difficult to determine just how good Grant truly was

Nevertheless, Grant is generally considered to have been the most accomplished black baseball player of the 19th century, and he certainly cannot be penalized for not being allowed to compete against the white major leaguers of the day.

Tony Lazzeri/Billy Herman/Bobby Doerr/Joe Gordon/

Red Schoendist/Nellie Fox

These six second basemen have been grouped together, even though each had a unique skill-set, because they all fit into the same category of being very good players who were questionable Hall of Fame selections. Let’s take a look at each one individually:

Tony Lazzeri was the Yankees’ regular second baseman from 1926 to 1937. He was a righthanded power hitter who, despite playing his home games in Yankee Stadium with its unfavorable dimensions for righthanded batters, managed to hit 18 home runs four times and drive in more than 100 runs on seven occasions. He also batted over .300 five times, hitting a career-high .354 in 1929. Lazzeri scored more than 100 runs twice, finished his career with a .380 on-base percentage, and was a solid fielder.

However, it must be remembered that Lazzeri played during a hitter’s era and never even came close to leading the league in any major offensive category. In addition, he was never considered to be the best second baseman in the game, and, with the possible exception of the 1926 and 1929 seasons, was rated well behind Charlie Gehringer in the American League. Furthermore, while it is true that he knocked in more than 100 runs seven times, it should be noted that Lazzeri spent much of his career batting sixth in the Yankee lineup behind Babe Ruth, Lou Gehrig, and Bob Meusel. While it is also true that Ruth and Gehrig hit a lot of home runs, thereby clearing the bases and cutting down on Lazzeri’s RBI opportunities, Ruth’s career on-base percentage was .474, Gehrig’s was .447, and Meusel was a lifetime .300 hitter. Therefore, Lazzeri clearly came to the plate with a lot of men on base. In the MVP voting, he finished as high as fourth one year, and finished in the top 10 two other times.

Billy Herman was the National League’s best second baseman from 1935 to 1943. During that period, he led the league in hits, doubles, and triples once each, knocked in 100 runs once, scored more than 100 runs five times, and finished in the top 10 in the MVP voting five times. He was selected to the All-Star team nine times and was a good fielder as well, having led league second basemen in fielding three times. He finished with a .304 career batting average and an on-base percentage of .367. In addition, in his years with the Chicago Cubs and Brooklyn Dodgers, he helped lead his team to four pennants.

However, during his prime, Herman was never considered to be the best second baseman in baseball. From 1935 to 1938, that distinction was held by Charlie Gehringer, and from 1939 to 1943, Joe Gordon was thought to be his superior. In addition, his run production was not on the same level as most of the other Hall of Fame second basemen. For his career, Herman totaled 839 RBIs and 1,163 runs scored. Those totals place him ahead of only Red Schoendist, Nellie Fox and Johnny Evers in runs batted in, and Tony Lazzeri, Bobby Doerr, Joe Gordon, Johnny Evers and Bill Mazeroski in runs scored—all men whose Hall of Fame credentials are certainly open to debate.

Bobby Doerr had good power for a middle infielder, hitting more than 20 homers three times and driving in more than 100 runs six times during his 14-year career with the Boston Red Sox. He also batted over .300 three times and led the American League in triples once and slugging percentage once. He was also an outstanding defensive player, leading league second basemen in fielding four times. Doerr was selected to the All-Star team nine times and finished in the top 10 in the MVP voting twice.

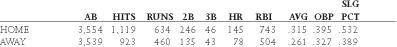

However, Doerr’s offensive numbers were inflated by the fact that he was a righthanded hitter playing all his home games in Fenway Park. All one needs to do to see just how much he benefited from playing in Fenway is to take a look at the home and away numbers he posted throughout his career:

From this graphic, it becomes apparent that Doerr was a Hall of Famer when he played at Fenway but just a pretty good player when he performed elsewhere. In addition, Joe Gordon, the Yankees second baseman of the same period, was selected ahead of Doerr by

The Sporting News

for its major league All-Star team from 1939 to 1942, and again in 1947 and 1948. Gordon also fared better than his rival in the annual MVP voting, winning the award in 1942 and finishing in the top 10 four other times. Factoring into the equation the ballparks in which they played their home games, a look at the career numbers posted by Doerr and Gordon reveals that the latter may well have been the better player:

Yet, Doerr was elected to the Hall of Fame in 1986, while Gordon wasn’t voted in until 2009. That last fact can most likely be explained by the presence of Ted Williams on the Veterans Committee when Doerr was selected. Williams, an extremely influential and imposing speaker, was Doerr’s teammate in Boston for ten seasons. He always spoke very highly of Doerr’s playing ability, and undoubtedly made a strong impression on the other Committee members.

Joe Gordon was one of the most prolific offensive second basemen in baseball history. A righthanded batter who spent the better part of his career playing in spacious Yankee Stadium, Gordon managed to hit 253 home runs in fewer than 6,000 at-bats in his 11 big-league seasons. He topped 20 homers in seven of those years, surpassing the 30-homer mark on two separate occasions. He also knocked in more than 100 runs four times and scored more than 100 runs twice. Gordon had his two best years in New York in 1940 and 1942. In the first of those campaigns, he hit 30 home runs, drove in 103 runs, batted .281, and scored a career-high 112 runs. In 1942, he hit 18 homers, knocked in 103 runs, and batted a career-best .322 en route to being named the American League’s Most Valuable Player. Gordon also had an exceptional year for the Cleveland Indians in 1948, establishing career-highs with 32 home runs and 124 runs batted in, scoring 96 times, and batting .280. A perennial All-Star, Gordon was named to the American League All-Star team in nine of his eleven seasons, and also finished in the top ten of the league MVP balloting a total of five times.

Still, several legitimate arguments can be waged against Gordon’s 2009 selection by the Veterans Committee. Missing two full seasons to time spent in the military during World War II, Gordon’s career was relatively short. Not only did he play just 11 years, but Gordon compiled barely over 5,700 at-bats. As a result, he finished with fairly modest career numbers, failing to surpass either 1,000 runs batted in or 1,000 runs scored. In addition, Gordon never finished higher than third in the league in any major offensive category. Furthermore, Gordon’s .268 career batting average was not particularly impressive, although he posted a solid .357 on-base percentage and a .466 slugging percentage, unusually high for a second baseman. Gordon was generally considered to be one of the more acrobatic middle infielders of his era. Yet he committed as many as 28 errors in a season five different times, topping 30 miscues on two separate occasions. And his career fielding percentage of .970 was ten percentage points lower than the mark of .980 compiled by his contemporary Bobby Doerr.

Red Schoendist teamed with shortstop Marty Marion from the mid-1940s to the early 1950s to give the St. Louis Cardinals probably the finest double-play combination of that period. Schoendist was an excellent fielder, having led National League second basemen in fielding six times. He was also a solid hitter, leading the league in hits and doubles once, and finishing second in batting once, in 1953. That season was Schoendist’s best as he hit 15 home runs, knocked in 79 runs and batted .342. He finished in the top 10 in the MVP voting four times and was selected to the All-Star team nine times.

The thing about Schoendist, though, is that, while he may have had three or four seasons in which he was considered to be the best second baseman in the National League, with the possible exception of that 1953 season, he was never considered to be the best major league player at his position. During the 1940s, both Doerr and Gordon were rated above him, during the early 1950s, Jackie Robinson was considered to be his superior, and, later in the decade, Nellie Fox was rated ahead of him. Thus, what we have is someone who was a very solid and dependable player, but not someone who truly stood out among his peers. It should be mentioned that Schoendist may well have been elected to the Hall partly because of the success he had as the Cardinals manager after his playing career was over. However, the feeling here is that a man should be elected on the strength of either his playing career or his managerial career, but not both. When selections are made using both as the basis, the Hall of Fame standards will invariably suffer.