Baseball's Hall of Fame or Hall of Shame (11 page)

Although he was considered to be a below-average defensive player, having led American League shortstops in errors five times, Luke Appling’s hitting justifies his place in Cooperstown. He batted .310 lifetime, and compiled an on-base percentage of .399, with 2,749 hits and 1,319 runs scored. He won two batting titles, leading the league in 1936 with a mark of .388 that remains the all-time record for shortstops. He also knocked in 128 runs, scored 111 others, and totaled 204 hits that year. Appling batted over .300 fourteen times during his career and was selected to the All-Star Team seven times. Despite his defensive shortcomings, he was named the outstanding major league shortstop by

The Sporting

News

three times, and finished in the top 10 in the MVP voting three times, finishing second twice.

George Davis/Joe Sewell/

Lou Boudreau/Robin Yount

These are the last four shortstops who clearly belong in Cooperstown.

George Davis, whose career spanned the last decade of the 19th century and the first decade of the 20th, was arguably the finest shortstop to play in the major leagues prior to Honus Wagner. Why he was not elected to the Hall of Fame by the Veterans Committee until 1998 is somewhat confusing, especially when one considers some of the lesser shortstops who were inducted long before him.

Davis finished his career with a .295 batting average, a .361 on-base percentage, 163 triples, 451 doubles, 2,660 hits, 1,437 runs batted in, 1,539 runs scored, and 616 stolen bases—all outstanding marks for a player from his era. Those figures are even more impressive when they are compared to the statistics compiled by some of the other shortstops who have been elected to Cooperstown, something we will do a bit later. Davis led the National League with 136 runs batted in 1897, one of three times he topped the 100-RBI mark. He also scored more than 100 runs five times, stole more than 40 bases five times, including a career-high 65 in 1897, and batted over .300 nine straight years, from 1893 to 1901, bettering the .340 mark four times. He was also a fine fielder, leading league shortstops in fielding no fewer than four times.

For much of the 1920s, Joe Sewell was the best shortstop playing in the major leagues. During the entire decade, he failed to hit at least .300 only one time, batting .299 in 1922. Playing for the Cleveland Indians, he was easily the best shortstop in the American League from 1921 to 1929, and he was superior to the top shortstops in the National League (Travis Jackson, Dave Bancroft, Glenn Wright, and Rabbit Maranville) in most of those seasons.

Although he was an outstanding defensive shortstop, Sewell was perhaps best known for hardly ever striking out. He is the holder of every major season and career record for fewest strikeouts by a batter, fanning only 114 times in 14 seasons and 7,132 at-bats, and setting a single-season record in 1932, when he struck out only three times in 503 at-bats. He was also a productive hitter, finishing his career with a .312 batting average, 1,055 runs batted in, 1,141 runs scored, and an on-base percentage of .391. Sewell knocked in and scored more than 100 runs in a season twice each, batted over .300 nine times, and led the A.L. in doubles once.

After leading league shortstops in fielding three times, he was moved to third base by the Yankees after they acquired him in a trade prior to the 1931 season. He spent three seasons there, solidifying New York’s infield and helping them to the pennant and world championship in 1932. During his career, Sewell finished in the top 10 in the MVP voting four times.

During the 1940s, there was no finer all-around shortstop in baseball than the Cleveland Indians’ Lou Boudreau. Selected to the American League All-Star Team eight times during that decade, he batted over .300 four times, drove in more than 100 runs twice, scored more than 100 once, and finished with more than 40 doubles four times. Boudreau led the American League in batting once, and in doubles three times, and was also an outstanding defensive player, leading league shortstops in fielding no fewer than eight times. He had his finest season in 1948 when, as player-manager for the Indians, he established career-highs in home runs (18), RBIs (106), and batting average (.355), en route to winning the A.L. MVP Award. Boudreau also finished in the top 10 in the voting seven other times.

Robin Yount is the only player in major league history to win an MVP Award at two of the most demanding positions on the diamond, shortstop and centerfield. Although his career numbers are not particularly overwhelming—if he were to be judged as an outfielder—they are extremely impressive when he is looked upon, primarily, as a shortstop.

That is the position Yount played for the Milwaukee Brewers in his first 11 seasons, from 1974 to 1984. Coming up to the Brewers as a skinny 18 year-old, it took Yount a few seasons to develop into the formidable player he eventually became. But, from the late 1970s to the early ’80s, he was as good as any shortstop playing in the major leagues, and clearly the best in the American League.

Yount had his finest season in 1982, when he won the first of his two MVP Awards. That year, he hit 29 homers, knocked in 114 runs, batted .331, and led the league with 46 doubles, 210 hits, and a .578 slugging percentage. After being shifted to the outfield in 1985 as a result of an injury to his throwing shoulder, Yount won the award a second time in 1989. That season, he hit 21 homers, knocked in 103 runs, and batted .318.

During his career, Yount hit 251 home runs, drove in 1,406 runs, scored 1,632 others, batted .285, and compiled 3,142 hits, all outstanding numbers, especially for a shortstop. He hit more than 20 homers four times, knocked in over 100 runs three times, scored more than 100 runs five times, and batted over .300 six times.

Rabbit Maranville/Travis Jackson/

Pee Wee Reese/Luis Aparicio

These four men have been grouped together because, while they were all quite different as players, they could all be described as marginal Hall of Fame candidates. Let’s examine each one’s credentials separately:

Playing mostly for the Boston Braves and Brooklyn Dodgers, Rabbit Maranville spent 24 seasons in the big leagues. He was considered to be a spectacular fielder, but was a below-average hitter, even for a shortstop. Coming up to the majors in 1912, Maranville spent his first eight seasons hitting in the Deadball Era, when mediocre batting averages were the norm. However, he played until 1935, and, even after batting averages began skyrocketing during the 1920s, Maranville never hit any higher than .295, and was able to top the .280 mark only three times during his career. He never drove in more than 78 runs in any season, and scored 100 runs only once, topping 80 only four times. He finished his career with a batting average of .258, only 28 home runs, and on-base and slugging percentages of only .318 and .340, respectively.

However, Maranville, in over 10,000 career at-bats, was able to compile 2,605 hits, 1,255 runs, 380 doubles, 177 triples, and 291 stolen bases—all very respectable numbers. In addition, he led National League shortstops in fielding five times and always seemed to do well in the MVP voting, finishing in the top 10 four times, even though no award was presented in the N.L. in any of the seasons from 1915 to 1923. Another thing in his favor is that he was elected by the BBWAA, not by the Veterans Committee. In fact, prior to his election in 1954, he always did well in the balloting. Therefore, one must assume that the baseball writers of his day held him in high esteem. It is also likely that he possessed many intangible qualities that statistics simply do not reflect.

Travis Jackson, the New York Giants regular shortstop for much of the 1920s and 1930s, finished his career with a batting average of .291, 135 home runs, and a slugging percentage of .433—all very respectable numbers for a shortstop. He also drove in more than 100 runs once, finished in the top 10 in the MVP voting four times, and was selected to

The Sporting News’ All-Star Team

three times.

However, in 15 big league seasons, from 1922 to 1936, Jackson appeared in more than 120 games only eight times and accumulated as many as 500 at-bats only six times. He never came close to leading the league in any offensive category, scored more than 80 runs in a season only twice, and walked as many as 40 times only twice. He finished his career with only 6,086 at-bats, 1,768 hits, and 833 runs scored. He was elected to the Hall of Fame by the Veterans Committee in 1982.

Pee Wee Reese was the captain of those great Brooklyn Dodger teams that appeared in six World Series between 1947 and 1956. He was a fine shortstop and team leader, and was one of the few Dodger players who helped to make Jackie Robinson feel welcome when he joined the team in 1947. During his career, Reese led the National League in stolen bases, walks, and runs scored once each, and led league shortstops in fielding once.

He was selected to the All-Star Team ten times and finished in the top 10 in the MVP voting eight times. He was the top shortstop in the National League from 1946 to 1953 and, based on the support he received in the MVP voting, was obviously thought of as being an extremely valuable and important player to the Dodgers.

However, playing in a fairly decent era for hitters, and in Ebbetts Field—an excellent hitter’s park—Reese finished his career with only a .269 batting average and 2,170 hits. He batted over .300 only once, and scored more than 100 runs only twice. In addition, he never had a season in which he could be classified as the best shortstop in baseball (from 1946 to 1953, that title was passed between Lou Boudreau, Phil Rizzuto, and Vern Stephens). He was selected by the Veterans Committee two years after Jackson, in 1984.

Luis Aparicio spent 18 seasons in the major leagues, playing for the Chicago White Sox, Baltimore Orioles, and Boston Red Sox. Coming up to the White Sox in 1956, Aparicio brought something to the American League that it had been lacking since the Deadball Era—daring base-running that epitomized the aggressive style of play employed by the “Go-Go Sox” of his time. Starting in 1956, he led the league in stolen bases nine straight seasons, topping the 50-mark four times. He was also an exceptional defensive player, leading the league’s shortstops in fielding eight times. He was selected to the All-Star Team ten times and finished in the top 10 in the MVP voting twice.

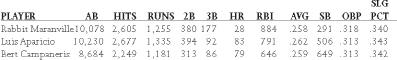

However, aside from his base-stealing ability, Aparicio was actually a below-average offensive player. During his career, he hit over .300 only once, hitting as high as .280 only one other time. He never scored 100 runs in a season, and his career on-base percentage was only .313. If you take a look at his numbers, they actually bear a remarkable resemblance to those compiled by Rabbit Maranville and, to a lesser degree, Bert Campaneris—someone who received very little support in the Hall of Fame balloting:

Maranville and Aparicio were virtually equal as run producers (that is, runs scored plus runs batted in). Aparicio hit more home runs and stole more bases, but Maranville had twice as many triples. Other than that, their numbers are practically identical.

Aparicio and Campaneris, both leadoff men, drove in runs, and scored them at virtually the same rate. Campaneris actually had a little more power and, in fewer at-bats, stole many more bases. It should be noted, though, that he was not as strong as Aparicio defensively. In addition, Aparicio was never considered to be the best shortstop in baseball. Early in his career, Ernie Banks held that distinction, and the torch was later passed to Maury Wills and, for one or two seasons, players such as Zoilo Versailles, Jim Fregosi, Rico Petrocelli, and Campaneris. Even in the American League, the only seasons in which he was rated as the top shortstop were 1959 and 1960.

The question that follows then is this: Where do Maranville, Jackson, Reese, and Aparicio stand as legitimate Hall of Famers? The feeling here is that none of the four men was truly outstanding enough to be viewed as anything more than a borderline candidate, at best. Their selections should all be viewed as extremely questionable. Of the four, due to his lack of plate appearances and relatively low career totals, Jackson’s election seems to be the most fallible. Maranville, because of his repeatedly good showings in the MVP and Hall of Fame balloting, and Reese, because of the excellent support he received in the MVP voting, and for all his appearances on the All-Star team, appear to be the most legitimate. But, the selections of all four men should be viewed with a great deal of skepticism.

Dave Bancroft

In 1971, the Veterans Committee, under the influence of two of its members, Frankie Frisch and Bill Terry, both of whom played with the former shortstop, elected Dave Bancroft to the Hall of Fame. Bancroft originally came up with the Philadelphia Phillies in 1915 and, as a rookie, helped them win the National League pennant. He was an outstanding fielder who was known much more for his defense than he was for his hitting. In his five years with the Phillies, he never batted higher than .272 and, in 1916, hit only .212. However, Bancroft benefited as much as anyone from the offensive resurgence that was ushered in by the 1920s. After being traded to the New York Giants during the 1920 season, he never hit less than .299 over the next four seasons, peaking at .321 in 1922. He also scored more than 100 runs in three of those seasons. Traded to the Boston Braves after the 1923 season, Bancroft batted over .300 twice more, in 1925 and 1926, before being traded to the Dodgers and, eventually, back to the Giants for his final season.