Baseball's Hall of Fame or Hall of Shame (41 page)

Those are very good stats, but borderline Hall of Fame numbers. However, Walker’s statistics will always be viewed with a great deal of skepticism since he compiled the majority of them playing in Colorado’s Coors Field, a notoriously good hitter’s ballpark. Colorado’s thin air enables balls to travel much further than they do in other ballparks, resulting in significantly higher home run totals and batting averages for hitters fortunate enough to call Colorado their home. The members of the BBWAA are certain to take that into consideration when they evaluate Walker’s qualifications once his name is added to the eligible list. Thus, in all likelihood, Walker will rightly be denied admission to Cooperstown.

Mike Mussina

One of baseball’s winningest pitchers for much of the past two decades was Mike Mussina. In 2008, the righthander finished with double-digit victories for the 17th consecutive season, winning his 270th game in the process.

Mussina spent the first 10 years of his career with the Baltimore Orioles, becoming a regular member of the team’s starting rotation in 1992, his second year with the club. Mussina was one of the American League’s best pitchers that year, compiling a record of 18-5, along with an outstanding 2.54 earned run average. He finished fourth in the Cy Young voting at the end of the season. Mussina also pitched extremely well for the Orioles in 1994, 1995, and 1999, posting won-lost records of 16-5, 19-9, and 18-7, respectively, along with earned run averages of 3.06, 3.29, and 3.50. Mussina continued his excellent pitching after signing on with the Yankees as a free agent prior to the start of the 2001 season. In his first year in pinstripes, he finished 17-11 with a 3.15 ERA. Mussina also posted records of 18-10, 17-8, and 20-9 in his eight years in New York, becoming, in 2008, the oldest pitcher in baseball history to win 20 games for the first time in his career.

In all, Mussina won at least 18 games six times, posting at least 15 victories five other times. He also pitched to an ERA below 3.30 six times. Mussina ended his career in 2008 with a record of 270-153. His earned run average over 18 major league seasons was 3.68. Considering the hitter’s era during which Mussina compiled those numbers, they might be good enough to earn him admittance to Cooperstown some time during his period of eligibility. Furthermore, it must be remembered that the Orioles were not a very good ballclub his first few years with the team and, also, that he spent many of those years pitching in Camden Yards, a veritable hitter’s paradise.

Nevertheless, Mussina’s detractors will point to the fact that he was never considered to be the best pitcher in the American League. In fact, he finished higher than fourth in the Cy Young balloting only once. He also led league pitchers in a major statistical category only three times, and he never particularly distinguished himself during the postseason. In nine playoff and World Series appearances, covering 16 postseason series, Mussina compiled a won-lost record of only 7-8, while pitching to a 3.42 earned run average. In addition, Mussina’s earned run average exceeded 4.40 in five different seasons, and, in his years in New York, he was rarely considered to be the best pitcher on his own team’s staff.

Still, Mussina’s total body of work is quite impressive. Few pitchers of his generation won as many as 15 games 11 different times, and few posted as many as 270 victories over the course of their careers. Although he finished as high as second in the Cy Young voting only once, Mussina placed in the top five in the balloting a total of six times. And, although he was a league-leader in a major statistical category only three times, Mussina finished second in wins three times, and placed in the top five in earned run average a total of nine times. He also was named to five All-Star teams and collected seven Gold Gloves during his career.

After winning 20 games for the first time in 2008, Mussina surprisingly elected to retire at the conclusion of the season, just 30 victories short of the magical 300-mark. Had Mussina hung around long enough to reach that plateau, it would have been extremely difficult to deny him a place in Cooperstown when he eventually decided to call it quits. But, as things stand now, the feeling here is that Mussina probably falls just a bit short, and should be viewed very much as a borderline candidate. Nevertheless, he deserves to be elected at least as much as about a dozen other pitchers currently in Cooperstown, including 300-game winners Don Sutton and Phil Niekro.

STILL ACTIVE FUTURE HALL OF FAMERS

This next group of Future Hall of Famers is comprised of those players who are currently active, but who have already accomplished enough during their careers to merit induction. In most cases, these are players who are in the twilight of their careers. However, in some instances, the players still appear to have several fine seasons ahead of them, but have performed at such a dominant level during their time in the major leagues that it would be impossible to find fault with their elections even if they were never to play another game. Following is a list of these men:

Ken Griffey Jr.

Frank Thomas

Manny Ramirez

Randy Johnson

Pedro Martinez

Tom Glavine

Mariano Rivera

Ken Griffey Jr.

Once considered the leading candidate to break Hank Aaron’s career home run record, Ken Griffey Jr. was victimized by a series of devastating injuries that ended his 2001–2004 seasons prematurely, and all but ended his pursuit of that cherished mark. But, prior to that, Griffey already established himself as one of the most dominant players of his era, as one of the finest all-around centerfielders ever to play the game, and as a certain Hall of Famer when his playing days are over.

After arriving in the big leagues four years earlier, Griffey had his first great season for the Seattle Mariners in 1993, hitting 45 home runs, knocking in 109 runs, scoring another 113, and batting .309. After hitting 40 homers, driving in 90 runs, scoring 94 others, and batting a career-high .323 during the strike-shortened 1994 campaign, Junior missed much of the 1995 season with an injury. However, he returned the following year, and, over the next four seasons, was arguably the best all-around player in baseball. Here are his numbers from those years:

1996:

49 HR, 140 RBIs, .303 average, 125 runs scored

1997:

56 HR, 147 RBIs, .304 average, 125 runs scored

1998:

56 HR, 146 RBIs, .284 average, 120 runs scored

1999:

48 HR, 134 RBIs, .285 average, 123 runs scored

Griffey was selected as the American League’s Most Valuable Player in 1997, one of seven times he has finished in the top 10 in the balloting. He has also been chosen for the All-Star Team 13 times. Griffey has hit more than 40 homers seven times, driven in more than 100 runs eight times, scored more than 100 runs six times, and batted over .300 eight times. In all, he has led his league in home runs four times, runs batted in once, runs scored once, and slugging percentage once. At the conclusion of the 2008 campaign, he had 611 home runs, 1,772 RBIs, 1,611 runs scored, and a batting average of .288.

After appearing in a total of only 337 games for the Cincinnati Reds between 2001 and 2004, Griffey made a stirring comeback in 2005, hitting 35 home runs, driving in 92 runs, scoring 85 others, and batting .301. Despite missing 92 games over the next three seasons, Griffey combined for 75 home runs and 236 runs batted in. Griffey will be 39 at the start of the 2009 campaign and has lost any chance he once had of establishing a new home run record. But the time he missed due to injury did not prevent him from claiming the fifth spot on the all-time home run list. Nor will it prevent him from being elected to Cooperstown the first time his name appears on the ballot.

Frank Thomas

Four injury-marred, mostly unproductive seasons during the second half of his career appeared to greatly diminish Frank Thomas’ chances of eventually being inducted into Cooperstown. His claim to baseball immortality was made even more tenuous by the somewhat one-dimensional nature of his game, which forced him to spend the second half of his career almost exclusively as a designated hitter. But, in the end, the tremendous offensive productivity displayed by Thomas throughout much of his long and illustrious career should earn him a spot in the Hall of Fame.

After joining the White Sox in 1990, Thomas became the team’s regular first baseman the following year. In each of the next eight seasons, he hit more than 20 homers, knocked in more than 100 runs, drew more than 100 bases on balls, and scored more than 100 runs. In seven of those eight years, he batted well over .300. In fact, Thomas is the only player in baseball history to hit .300 with at least 20 homers, 100 RBIs, 100 runs scored, and 100 walks in seven consecutive seasons. He is also one of only four players to drive in at least 100 runs in his first seven years in the big leagues.

In his first seven seasons, Thomas won a batting title, led the American League in walks and on-base percentage four times each, and in slugging percentage, runs scored, and doubles once each. He won two Most Valuable Player Awards, finished in the top ten in the voting every year, and was named to five All-Star teams. He was arguably the most feared hitter in the game, and was one of its ten best players and top two first basemen in every season.

Thomas was the best first baseman in baseball in both 1993 and 1994, being named the American League’s MVP at the end of each of those seasons. In 1993, he hit 41 home runs, knocked in 128 runs, batted .317, scored 106 runs, and walked 112 times. In the strike-shortened 1994 campaign, Thomas hit 38 homers and drove in 101 runs in only 399 official at-bats, while batting .353, scoring 106 runs, and walking 109 times. He was, once again, the best first baseman in the game in 1996, when he finished with 40 home runs, 134 runs batted in, a .349 batting average, and 110 runs scored. Thomas was also among the game’s elite players in both 1997 and 2000. In the first of those years, he hit 35 home runs, drove in 125 runs, scored 110 others, and led the league with a .347 batting average. Three years later, he established new career highs with 43 homers, 143 runs batted in, and 115 runs scored, while batting .328 and finishing second in the league MVP voting.

Nevertheless, Thomas’ status as an eventual Hall of Famer appeared to take a major hit over the next five seasons. Due to injuries, and to what some perceived to be a somewhat apathetic attitude, Thomas had only one quality season between 2001 and 2005. In three of those years, he failed to appear in more than 75 games for the White Sox. He missed almost all of the 2001 and 2005 seasons, and played in only 74 games in 2004. He did put up good numbers in 2003, though, hitting 42 home runs and driving in 105 runs. But Thomas’ ineffectiveness throughout much of that period seemed to make him a borderline Hall of Fame candidate. So, too, did his reputation for being a total liability in the field, which has caused him to spend the better portion of his career serving primarily as a designated hitter.

Yet, after leaving Chicago at the end of the 2005 season, Thomas had extremely productive years for Oakland in 2006 and Toronto in 2007. Over those two seasons, he combined for 65 home runs and 209 runs batted in, helping to restore his somewhat damaged reputation. More importantly, Thomas surpassed the 500-homer mark, practically guaranteeing him a place in Cooperstown when his career is over. If the baseball writers need any more convincing, they need only look at his other outstanding credentials.

Thomas has put together eight true Hall-of-Fame type seasons during his career. Aside from winning the MVP Award twice, Thomas has finished in the top ten in the balloting seven other times. He has been selected to the All-Star Team five times, a decent number for a potential Hall of Famer. He has won a batting title, and has led his league in on-base percentage four times. In fact, his career on-base percentage of .419 is the fourth highest among active players, and places him 21st on the all-time list. His .555 career slugging percentage also places him among the top 25 all-time. In addition to his 521 career home runs, Thomas has driven in 1,704 runs, scored 1,494 others, and compiled a .301 lifetime batting average. Those numbers should be good enough to get him into the Hall of Fame when his playing days are over.

Manny Ramirez

Manny Ramirez is far from a complete player. He is a below-average outfielder, a poor baserunner, and he possesses horrible baseball instincts. Furthermore, his attitude and mental approach to the game have often been questioned by management, the fans, the media, and, in some instances, even his own teammates. Ramirez has been known to sit out pivotal games with minor injuries, he frequently doesn’t hustle, and he generally seems to place his own personal interests ahead of those of his team. Perhaps that explains why, in spite of the prodigious offensive numbers he posts annually, Boston Red Sox management finally decided to rid itself of his exorbitant contract this past season, after beginning to explore opportunities to do so as early as 2002.

However, Ramirez is also a tremendous offensive player— one of the finest of his era. He has outstanding power, hits for an extremely high batting average, and is one of the best clutch hitters and greatest run producers of the modern era.

Ramirez first came up with the Cleveland Indians in 1993. In six full seasons with the Indians, he topped 30 homers and 100 runs batted in five times each, scored more than 100 runs twice, and batted over .300 five times. His two most productive seasons in Cleveland came in 1998 and 1999, both years in which he led the league in slugging percentage. In 1998, he hit 45 home runs, knocked in 145 runs, scored 108 others, and batted .294. The following year, he hit 44 homers, drove in a league-leading 165 runs, scored another 131, and batted .333. In 2000, his final year in Cleveland, Ramirez batted a career-high .351.

After signing on with the Boston Red Sox as a free agent prior to the start of the 2001 season, Ramirez continued his tremendous offensive productivity. He has hit more than 30 home runs and driven in more than 100 runs in seven of the last eight years, surpassing 40 homers and 125 runs batted in three times each. He has also scored more than 100 runs four times and batted over .300 six times during that period. In 2002, Ramriez led the American League with a .349 batting average. He had his two most productive seasons in Boston in 2004 and 2005. In the first of those years, Ramirez hit 43 home runs, knocked in 130 runs, scored another 108, batted .308, and finished third in the league MVP voting. The following season, he hit 45 homers, drove in 144 runs, scored 112 others, batted .292, and placed fourth in the MVP voting.

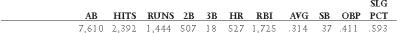

Over 14 full major league seasons, Ramirez has averaged 36 home runs and 118 runs batted in. He has topped the 30-homer mark 12 times, surpassing 40 on five separate occasions. He has also batted over .300 eleven times, topping the .320-mark seven times. A veritable RBI-machine, Ramirez has driven in more than 100 runs 12 times, knocking in at least 120 runs on seven separate occasions. He has also scored more than 100 runs six times. In addition to his batting title, Ramirez has led the league in home runs and runs batted in once each, and in on-base percentage and slugging percentage three times each. He has been selected to 11 All-Star teams, and has finished in the top ten in the league MVP voting a total of nine times, placing as high as third twice. Going into the 2009 season, here are his career statistics:

In spite of the amount of baggage Ramirez has always brought along with him throughout his career, those numbers should be good enough to get him into the Hall of Fame. But, at age 36, he figures to add to them significantly before his career is over. Ramirez would have to be considered a virtual lock for the Hall once his playing days are over.

Randy Johnson

As the dominant lefthander of the past 25 years, and as one of the very best pitchers of that same period, Randy Johnson is another who most certainly has a plaque waiting for him at Cooperstown when his playing days are over. With the possible exception of Steve Carlton, no lefthanded pitcher dominated opposing hitters the way Johnson did for much of his career since Sandy Koufax mesmerized National League batters during the 1960s. And, without question, not since Koufax did any lefthander intimidate opposing hitters the way Johnson did throughout much of his brilliant 21-year career.

Yet, it took Johnson time to develop into the great pitcher he eventually became. In his first five big league seasons, he struggled with his control, walking well over 100 batters three times. But, after gaining a greater command of the strike zone in 1993, Johnson became one of the best pitchers in baseball. In the 16 seasons since, he has been a 20-game winner three times, has won at least 16 games eight other times, and has garnered five Cy Young Awards.

Johnson had some truly outstanding seasons for the Seattle Mariners, finishing with records of 19-8, 18-2, and 20-4, in 1993, 1995, and 1997, respectively. However, he became the most dominant pitcher in baseball after moving to the National League during the 1998 campaign. Pitching for the Arizona Diamondbacks from 1999 to 2002, Johnson put together a string of seasons reminiscent of the ones Koufax compiled for the Dodgers during the 1960s. Here are his numbers from those four seasons:

1999:

17 wins, 9 losses; 2.48 ERA; 364 strikeouts

2000:

19 wins, 7 losses; 2.64 ERA; 347 strikeouts

2001:

21 wins, 6 losses; 2.49 ERA; 372 strikeouts

2002:

24 wins, 5 losses; 2.32 ERA; 334 strikeouts

Johnson led National League pitchers in strikeouts in each of those years, and also finished first in ERA three times, and in wins once. In being named winner of the Cy Young Award at the end of each of those seasons, Johnson joined Greg Maddux as the only pitchers ever to be so honored four consecutive years.

During his career, Johnson has led his league in wins once, ERA four times, strikeouts nine times, shutouts twice, and complete games four times. He has finished with an ERA under 3.00 seven times during his career, and has struck out more than 300 batters six times, surpassing the 200-mark on seven other occasions. Johnson has finished in the top ten in the league MVP voting twice, in the top five in the Cy Young balloting eight times, and has been selected to the All-Star team ten times. As of this writing, Johnson’s career record is 295-160, his ERA is 3.26, and, with 4,789 strikeouts, he trails only Nolan Ryan on the all-time list.

Pedro Martinez

While he has not been as durable as the other great pitchers of his era—Roger Clemens, Greg Maddux, and Randy Johnson— when healthy, Pedro Martinez has been as dominant as any of them. With a career record of 214-99 as of this writing, he has the best won-lost percentage, and his ERA of 2.91 is significantly lower than that of the other three men. Martinez has led his league in wins once, in ERA five times, and in strikeouts three times. He has been an eight-time All-Star, has placed in the top five in the league MVP voting twice, and has won the Cy Young Award three times, finishing in the top five in the voting another four times.

With the exception of his injury-plagued 2001 season, Martinez was at his very best from 1997 to 2002, rivaling Randy Johnson as the best pitcher in the game during that period. Let’s look at his numbers from his five best seasons:

1997:

17 wins, 8 losses; 1.90 ERA; 305 strikeouts

1998:

19 wins, 7 losses; 2.89 ERA; 251 strikeouts

1999:

23 wins, 4 losses; 2.07 ERA; 313 strikeouts

2000:

18 wins, 6 losses; 1.74 ERA; 284 strikeouts

2002:

20 wins, 4 losses; 2.26 ERA; 239 strikeouts

Martinez was the recipient of his league’s Cy Young Award following the 1997, 1999, and 2000 seasons, and, with the possible exception of Roger Clemens in 1997, was the best pitcher in baseball in each of those years. He was clearly among the top five pitchers in the game in all five seasons.

In all, Martinez has won at least 16 games six times, has finished with an ERA under 3.00 ten times, twice allowing fewer than two runs per contest, and has struck out more than 200 batters nine times, twice topping the 300-mark. Martinez’s career ERA of 2.91 is the lowest of any starting pitcher whose career began after 1980.

Should Martinez never pitch another game, his relatively low total of 214 victories might deter some members of the BBWAA from entering his name on their Hall of Fame ballots in his first year of eligibility. There is little doubt, though, that the majority of the writers will realize that the standard of excellence Martinez set for himself on the mound throughout his career earned him a first-ballot election to Cooperstown.

Tom Glavine

Lefthander Tom Glavine has never been the dominant pitcher that some of his contemporaries were through the years. He never possessed the overpowering fastball of Roger Clemens, the overwhelming fastball/slider combination of Randy Johnson, or either the great fastball or the superb curve of Pedro Martinez. And, for much of his career, he was overshadowed in Atlanta by his own teammate, Greg Maddux. But, while he may not have been a truly

great

pitcher, Glavine was, from 1991 to 2002, one of baseball’s most consistent winners, and one of its top hurlers.

In his first 16 seasons with the Atlanta Braves, Glavine was a 20-game winner five times, and won at least 16 games three other times. He led the National League in wins five times, and in shutouts and complete games once each. He was named to the All-Star Team eight times, finished in the top ten in the league MVP voting once, and placed in the top five in the Cy Young balloting six times, winning the award twice. Glavine won the award for the first time in 1991 with a record of 20-11 and an ERA of 2.55. He won his second Cy Young in 1998, compiling a record of 20-6 and a 2.47 ERA. Glavine has also put together seasons in which he compiled records of 20-8, 22-6, and 21-9. In each of his 20-win seasons, Glavine was among the five best pitchers in baseball. Glavine has also posted an ERA below 3.00 six times. As of this writing, his career mark is 3.54, and his won-lost record is 305-203.

When Glavine’s career is over and he eventually becomes eligible for induction into Cooperstown, there is little doubt that his 300 victories will prompt many members of the BBWAA to vote for him the first time his name appears on the ballot. If Glavine is not elected in his first year of eligibility, he most certainly will be voted in shortly thereafter.

Mariano Rivera

As of 2008, only five relief pitchers have been inducted into Cooperstown—Hoyt Wilhelm, Rollie Fingers, Dennis Eckersley, Bruce Sutter, and Goose Gossage. Unless someone such as Lee Smith is inducted in the next few years, there is little doubt that Mariano Rivera will eventually become the sixth reliever to be enshrined in the Hall once his playing days are over. Over the course of his brilliant career, Rivera has established himself as the greatest closer in baseball history.

Rivera has been a dominant pitcher ever since he first served as set-up man to closer John Wetteland for the Yankees during New York’s run to the 1996 world championship. After assuming Wetteland’s role the following year, Rivera became the very best closer in the game. Over the past 12 seasons, he has been as close to automatic as anyone in baseball, finishing with at least 36 saves nine times during that period. He has reached 40 saves six different times, and has surpassed 50 on two separate occasions. Rivera has compiled an ERA under 2.00 eight times, and has finished with a mark over 3.00 only once (3.15 in 2007). Over the course of his career, he has surrendered only 800 hits in 1,024 innings of work, and his strikeout-to-walk ratio is better than 3 to 1.

Rivera has led American League relief pitchers in saves three times, has been selected to nine All-Star teams, has finished second in the Cy Young balloting once, and has placed third in the voting on three other occasions. He finished third in the balloting for the first time in 1996, when he compiled a record of 8-3, with a 2.09 ERA and 130 strikeouts in 108 innings pitched as a set-up man. He placed third in the balloting again in 1999, when he compiled a 4-3 record, with 45 saves and a 1.83 ERA, while surrendering only 43 hits in 69 innings of work. He finished third in the voting again in 2004, when he finished 4-2, with a league-leading 53 saves, and a 1.94 ERA. Rivera finished runner-up in the balloting in 2005, when he compiled a record of 7-4, with 43 saves and a 1.38 ERA, while allowing just 50 hits in 78 innings of work.

Rivera has not only been the best relief pitcher in baseball for most of his career, but has also been one of the greatest postseason pitchers in baseball history. In 76 playoff and World Series contests between 1996 and 2007, he compiled a won-lost record of 8-1 and an ERA of 0.77, while saving 34 games and allowing only 72 hits in 117 innings of work. Perhaps more than any other player, he was responsible for New York’s successful playoff run that led to four world championships in five seasons between 1996 and 2000.

Rivera concluded the 2008 campaign with 482 career saves, placing him second on the all-time list. He also has posted a brilliant 2.29 ERA during his 14 big-league seasons. When Rivera eventually becomes eligible for induction to Cooperstown, it shouldn’t take the BBWAA long to elect him. Indeed, he is likely to join Dennis Eckersley as only the second reliever to be inducted in his first year of eligibility.

Borderline Hall of Fame Candidates

There are several other active players in the latter stages of their careers who could be classified as borderline Hall of Fame candidates. This list of players includes: