Battleworn (15 page)

Authors: Chantelle Taylor

I think that regardless of how mentally tough you think you are, when it’s your guys who are bleeding, you feel pretty vulnerable. That’s just how I feel today. My desire to not hear someone else’s war stories has gone. I want to hear anyone else’s story but my own. I am not interested in B Company’s holding Nad-e Ali. The mission to get the turbine to Kajaki Dam couldn’t be further from my thoughts. I feel dejected and uncharacteristically negative. I am angry that we are always on the receiving end. Every day, we keep getting hit; every other day, we keep taking casualties. We don’t have the kit or capabilities to sustain any of it. Our Osprey body armour is not holding up to the job at hand. I invested in BlackHawk pouches that fitted the armour much better, and I am now thankful to have done so.

It suddenly dawns on me that all this agitation is covering up my concern about losing one of our own. Today’s KIA was Afghan, but it could just as easily have been one of ours. I don’t want to acknowledge the black body bags underneath the old desk in the corner of the aid post. B Company has grown close, and I have started to look at a lot of the guys as family.

I go back to the medical room: it’s like a scene from a horror film, with blood everywhere after the treatment of the injured. Jen and I scrub it with what we have. We do this in silence of course, all very British and stiff upper lip. Sometimes saying nothing is better; a big fat discussion is the last thing we need.

There was more to come for the PMT, who had to make their way back to Lash after being smashed on the way in. Strangely enough, they were smashed on the way back out as well. They report back with casualties, but none are serious. When you think about them making the journey back, knowing they were probably going to get hit, it shows the kind of blokes they are. But that’s what’s expected, and all the guys do it without question.

We soon realise that the Taliban are cutting off our supply line, which is bad news. They litter most of our routes with IEDs, so road moves become impossible. Disruption can sometimes be a far more effective weapon than rockets. All of the wars in history tell you that.

Surprisingly, Monty’s crew has been left alone, as has Flashheart’s kandak. The Taliban have already had their success today. Later in the evening, we endure a small-arms attack, but compared to earlier events, it’s pretty tame. The Taliban body count is already at thirty; somehow, though, their fighters still come.

Earlier in the tour the Americans flooded Garmsir, a town which lies on the southern tip of Helmand Province. They deployed more than two thousand US Marines in the form of 24 Marine Expeditionary Unit; together with A Company of 5 Scots, they drove the Taliban out of Garmsir. This forced the insurgents to find another route up to the Sangin Valley. Marjah and Nad-e Ali have thus become the Taliban’s new ‘highway to hell’. A moment no doubt played out to AC/DC, in my head anyway.

We welcome Monty’s platoon back in to the base. They can’t believe that they missed all the drama. There is a lot to talk about, and our room stays lively until around 2000 hours. Every roll mat in the base is full apart from the radio stag and the young Jocks manning the wall. We work a rotation to cover the radio net, doing two hours at night and two hours in the day. I am on death stag tonight, and it’s hard to stay focused. Radio checks take place every fifteen minutes. I wonder if anyone in brigade HQ has actually woken up to the fact that we are in a world of shit down here. It seems that the turbine move up north is taking all of the news. The latest rumour is that 3 PARA will be sent down here to boost numbers and conduct offensive operations.

The Pathfinder (PF) Platoon are also rumoured to be conducting offensive ops in Marjah; this will hopefully smash the Taliban before they get to Nad-e Ali. I start to run through some ridiculous trains of thought whilst listening to the white noise of the radio. What if we get stuck out here or the marines somehow can’t get in? What if the base gets overrun or one of our helicopters gets shot down? This is what happens when you get the radio watch in the early hours, the ‘death stag’. I am pickling my own brain with this nonsense.

It’s dark and quiet, so I keep a constant paranoid watch on the entrance to the makeshift ops room. Any shadows are starting to look like potential threats. My rifle is in my lap, barrel pointing towards the door. The longer I sit here, the worse it gets. An incident that took place up north in one of the FOBs suddenly hits my now-twisted psyche. One of the Afghan soldiers decided to fire a burst into a room where some of 2nd Battalion, Parachute Regiment (2 PARA) lay sleeping. He shot three of them; thankfully, none of them were killed – good time to think about it, though.

My stag is coming to an end, and it’s definitely time for some bivvy bag action to clear the fuzziness out of my pan-fried head. Jen’s on stag next, so it’s time to wake her. Probably the worst sound that any soldier will ever hear is someone whispering, ‘your stag!’ I hated it when I joined up, and I still hate it now.

The white noise from the radio continues as I lay down my head, and it takes at least another hour before I doze off.

Me, Sgt Chantelle Taylor, Helmand Province, Afghanistan, 2008; my final tour

The Argyle and Sutherland Highlanders (5 Scots) a ‘multiple’ of fighting men also known as a platoon minus.

The beloved Snatch Land Rover sitting behind the preferred open-top WMIK.

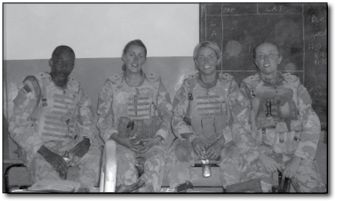

My medical team, LCpl Sean Maloney, Pte Abbie Cottle, me, and LCpl Jenny Young.

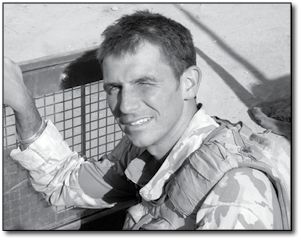

Sgt Richard ‘Monty’ Monteith, B Company (5 Scots).

Lcpl Kev Coyle and me; ‘battleshock’ after our first night on ‘that roof’ in Nade-Ali.

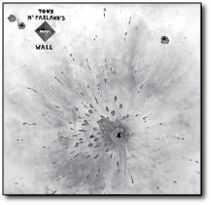

Afghan soldier ‘Medi’s’ direct hit with an RPG; unfortunately, Cpl Tony McParland got in the way.

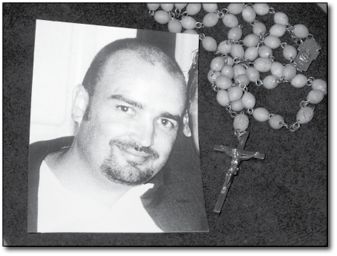

My brother David and the lucky rosary beads, kept in the inner sleeve of my body armour.

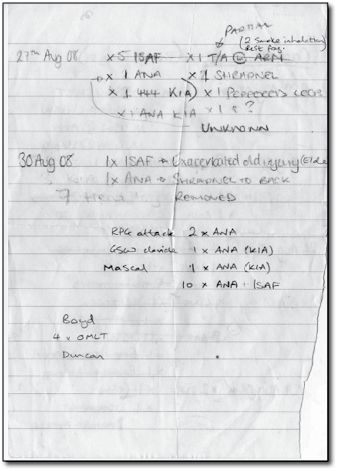

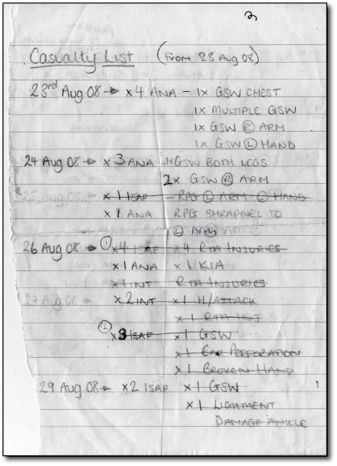

Original casualty list 1