Beatles (10 page)

Authors: Hunter Davies

I could understand the desire to protect Julia’s two daughters, as they were only teenagers in 1968, and John had been rather bitchy about their father, so I agreed to all that. It was her determination to censor John’s account of himself that seemed very unfair.

Most memories of childhood are suspect. It’s what different people choose to remember that is interesting. Who had the better memory anyway, Mimi or John? John, by this time, was fed up with the whole subject and insisted I kept her happy at all cost, so I travelled to Bournemouth and went through the offending paragraphs line by line. Some of the bad language was removed and some wilder parts of his stories, and she was eventually pacified.

You will notice in the book that

Chapter 1

ends rather limply and abruptly with the phrase ‘John was as happy as the day was long’. This was at Mimi’s insistence. I gave in, a compromise, in order to keep in most of John’s other stories. She thought this would soften them. That was the truth about John’s childhood, as she saw it. I was relatively happy, as the other truths were still there as well, so readers could decide for themselves.

The book, when it was published, was greeted as a ‘candid’ biography by all the critics, on both sides of the Atlantic, and in Europe and Japan, and was even described as ‘the frankest authorized biography ever written’. I’ll spare you the details. It was, of course, a long time ago and lots of things have happened since then. I was upset, several years later, when John, in an interview, said that my book had been ‘bullshit’. This was at the time when he had got into his head that the whole Beatle image was a whitewash. As far as John and my book was concerned, I only

had to make minor changes, one to please John, the other to please Mimi.

I then had a lot of trouble with some of their side kicks at Apple, who took it upon themselves to try to alter things elsewhere in the book, on subjects such as drugs. The Beatles by this time had gone off to India, having read and approved the book. Their assistants, left behind in charge of the office, wanted several changes.

I managed, in the main, to fight them off, though I had many agonizing weeks, getting all the necessary approvals, trying to keep track of all the copies, and then the corrected copies, which were flying around. The Beatles themselves, having read their own individual copy, left it lying around at home, or at Abbey Road, or in the Apple office, so everyone was dying to find out if they figured in the book. John, in that letter asking me to make changes, also mentions that ‘Dot’s heard from Margaret something about her’. Dot was John’s housekeeper at the time, and was only mentioned once or twice. As for Margaret, I can’t even remember who she was.

I would not like to go through all those weeks again, but the worst was to come. I had forgotten that Brian Epstein had been the one responsible for the main contract, on their behalf. As he was now dead, the Epstein family demanded to see the manuscript. Legally, his mother had inherited his estate. I was therefore technically beholden to Mrs Queenie Epstein, an old lady who knew nothing about the pop world, and, even worse, nothing about Brian’s secret life, for the final clearance on the book.

You can imagine what she thought about any suggestions that Brian might be homosexual. She denied it. As far as she was concerned, it wasn’t true. I needed her signed agreement. We had by this time sold the American and several other rights, and the buyers naturally wanted to see the legal clearances.

Clive Epstein, Brian’s brother, was helpful, though of course he wanted to keep his mother happy. As her beloved son had died only recently, it was thought unseemly to go into all the

sordid details of his last couple of years. I hadn’t really written much about that and in the end I was persuaded to steer completely clear of his sex life, but I thought I did manage to make it fairly clear at the end of

Chapter 15

, where I said he had only one girlfriend in his life – and then continued to talk about his unhappy love affairs. I also described him as a ‘gay bachelor’. The word was not in such common use in England in those days, but it was enough to let many people know the truth.

Did it matter, Brian’s homosexuality? I did regret having to disguise it, as he himself had given me permission to mention it and it has been publicly stated since. With most people, their sex life is not relevant, either way, to their work, although these days many people in public life, at least in the arts and show business, make no effort to hide what sort of people they are. With Brian, I think it did matter and it was a vital clue to his personality, to his death, and also to the birth of his interest in the Beatles.

One of the strangest episodes in all the Beatle sagas is how such a person as Brian Epstein came to be interested in them in the first place. What attracted a public-school, well brought-up, middle-class Jewish boy, a rising businessman who loved Sibelius and had shown not the slightest personal interest in any sort of pop culture? What made him go along to see four scruffy, working-class yobbos in a smelly underground coffee bar? He fancied them. That was one explanation, though I was never able to spell it out. Most of all, he fancied John, jumping around in his leather gear and big cowboy boots. (The gossip, years later, was that he fancied Paul, as Paul was always supposed to be the prettiest Beatle, which couldn’t have been further from the truth. He liked them butch and aggressive, even when they didn’t like him – often

because

they didn’t like him sexually.)

Brian Epstein gave the Beatles to the world when others more worldly had already passed them by. They created themselves, their music and their performances; but in the wrong hands – nasty, grasping, short-term hands – their national launching would have been very different. According to popular theory,

Brian was simply a very smart Jewish businessman. He’d seen the money in them. In truth, he wasn’t a great businessman, as was shown later when many of his deals had to be rearranged. He wasn’t materialistic. Brian Epstein loved the Beatles, in every sense of the word. That’s all there was to it.

I had one good bit of luck, just as the book was going to press. I suddenly made contact with Freddie Lennon. He first reappeared in about 1964, when the news about John being a Beatle was pointed out to him by a washer-up in a hotel where he was working. As everyone in the Lennon family then refused to see or help him, he disappeared again, after having given a few interviews to various magazines.

John was quite amused by his reappearance, especially when he produced a record, though he knew that Mimi and the rest of the family would never forgive him if he helped Freddie in any way. Freddie, after all, had deserted his wife and child.

In early 1968, I finally tracked Freddie down to a hotel near Hampton Court, not very far from John’s home in Weybridge, where he was working as a dish washer.

‘I just live my own little life. Happy go lucky, that’s me. I like moving on. I don’t like the press finding out where I am, you know.’

He was still very upset that a couple of years earlier he arrived, unannounced, at John’s house and the door was slammed in his face. I met him several times, and rather warmed to him, and got him to take me through his early life, which made the basis for the first part of

Chapter I

in the book.

I asked him why he had deserted John and his wife. Freddie himself didn’t seem to know. He said he had been very unhappy to lose John, oh yes, it really upset him, especially after the time he spent with him at Blackpool.

‘That evening, after John was taken away,’ so Freddie told me, ‘I was singing at the Cherry Tree pub in Blackpool. I sang the Al Jolson song “Little Pal”. I sang the words “Little John” with tears in my eyes.’

I never knew whether to believe half the things Freddie told me, so I didn’t put everything in. I had of course no means of checking his own account of his early life, although I think in the book his exaggerations about his own brilliance are pretty clear, especially when he boasted about being ‘their best waiter’, and Julia’s mother loving ‘the bones of his body’. Or was this all true?

I told John the stories Freddie had come out with, and how he was living a hand-to-mouth existence once again, going from hotel to hotel, usually in the kitchen, always willing to give any bar audience a few songs, in the hope of enough money to buy a drink.

Some of his stories sparked off other memories in John’s mind, bringing back vague recollections of things Julia had told him about her early married days to Freddie. ‘I think they did have some good times together,’ said John. ‘I don’t really hate him now, the way I used to. It was probably Julia’s fault as much as his that they parted.

‘If it hadn’t been for the Beatles, I would probably have ended up like Freddie.’

I remember laughing at this at the time, though there is some truth in it. It is hard to imagine John fitting in with a proper job, or office hierarchy, or even managing to make a living as an artist or designer, not of course that he had passed any of his Art College exams. He would have become bored far too quickly. So he might well have ended up as a bum.

One night, John rang me and asked for Freddie’s home number. All I could give him was the hotel, as Fred was sleeping on somebody’s floor and didn’t have a phone. John didn’t want to ring the hotel, so I contacted it, and then went to see Freddie again. I told him John would now like to see him, but it had to be kept a complete secret. If it got out to the press, and worst of all, if Mimi heard, that would be it.

A meeting was fixed up between them and they got on very well. John found Freddie hilarious, which encouraged Freddie

to tell even wilder stories about his life and hard times. John started giving Freddie money, shoving wads of it in his hand, and when he discovered he had nowhere to live, he said that Freddie could move in with him for a while.

In the end, John set him up with a flat of his own. Freddie, now he was in the money again, was delighted, and moved into this flat with his 19-year-old girlfriend, who he was going to marry, so he told me.

As a thank-you for bringing them together, Freddie sent me a nice letter and a present of an early photograph of himself. I had been desperate for a photograph of a young Freddie to use in the book, but it arrived too late.

It shows him in a prisoner’s uniform, on board ship, holding up his number. Freddie must have been about 40 at the time, the same age as John was when he died. The resemblance is striking.

The book was already at the typist by the time I made contact with Freddie, which was why that first chapter is so staccato and jumpy. I simply poured in as much as I could about Freddie in the quickest possible time.

The book, as a whole, is a rather bumpy read. If I were writing it again now, I would try to improve the style, smooth out the wrinkles, polish the prose, stand back more and try to put things and people and events in perspective. Or would I? Perhaps its virtue is that it is of its time, a first-hand account of an unusual period, an eye witness report on the rise of a phenomenon, then at its height, soon to fall apart, although none of us knew it at the time. Just as well. Hindsight can make us all far too clever.

This is the simple story of the Beatles, exactly as it appeared in 1968. I hope you’ll enjoy the show.

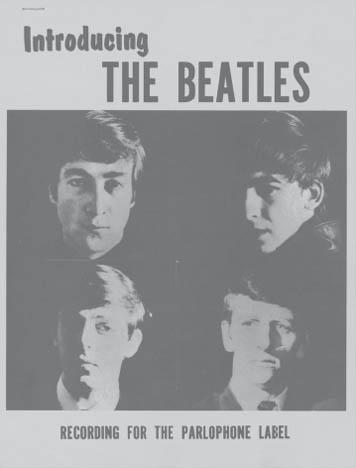

The first publicity photographs of the Beatles put out by Parlophone for their first record, ‘love Me Do’ in October 1962.

The first publicity photographs of the Beatles put out by Parlophone for their first record, ‘love Me Do’ in October 1962.part

1

1

john

Fred Lennon, John’s father, was brought up as an orphan. He went to the Bluecoat School in Liverpool, which at that time took in orphan boys. Fred was put into a top hat and tails and when he came out, so he says, he had received a very good education.

He was orphaned in 1921 at the age of nine when his father, Jack Lennon, died. Jack Lennon had been born in Dublin but had spent most of his life in America as a professional singer. He had been a member of an early group of Kentucky Minstrels. After he retired, he returned to Liverpool where Fred was born.

Fred left the orphanage at the age of 15, with his good education and two new suits to get him through life, and became an office boy. ‘You might think I’m bigheaded, but I’d only been there a week when the boss sent to the orphanage for three more boys. He said if they had only half the vitality I had, then they’d be all right. They thought I was terrific.’

Terrific or not, by the age of 16 Fred had left office work for the sea. He became a bell boy and eventually a waiter. He says he was their best waiter, but he had no ambition. He was so good that ships wouldn’t leave Liverpool unless they had Freddy Lennon on board, so he says.

It was just before he set out for his great career at sea that Fred Lennon started going out with Julia Stanley. The first meeting was just a week after he had left the orphanage.

‘It was a beautiful meeting. I was wearing one of my two new suits. I was sitting in Sefton Park with a mate who was showing me how to pick up girls. I’d bought myself a cigarette holder and a bowler hat. I felt that really would impress them.