Beatles (7 page)

Authors: Hunter Davies

Later, Pete did write a book. I hope he made a few bob from it. After all, he

was

a Beatle, at a vital time, as opposed to those temporary secretaries and chauffeurs who have rushed into print, despite knowing them only a few weeks, long after the real Beatle days were over.

Hamburg was very hard – I thought I’d never manage to get clear in my mind what had happened there. The Beatles were totally contradictory in their memories of how many times they went there, which order they played the various clubs, and which events had occurred at which time.

I had very long sessions with each of the Beatles and I realized what an important stage Hamburg had been, how it brought them together as a group, developed their personalities, gave them their own sound, and of course their new look. Nobody had tried to write about this vital period in their life, or been back to try and check what happened. I did not quite appreciate, till I got out there, that they were full of pills for so much of the time, trying to keep themselves awake for twelve-hour playing sessions. No wonder they had such hazy ideas about dates and places and people.

I went out to Hamburg in 1967 and visited all the clubs they played at and talked to as many people as I could find who

remembered them. I even got a copy of the record contract they made with Bert Kaempfert Production. This was clearly dated 5.12.1961, which was useful when I started to get the sequence of events straight. It showed, for a start, that Stu Sutcliffe had left the Beatles by then. (He was the Beatle who died in Hamburg in April 1962.)

In the eight-page contract, it gave them, in clause 4, the opportunity of ‘listening to their recordings immediately after completion thereof and of raising any possible objections on the spot’. That was a very fair clause, for an unknown foreign backing group, producing a few quick numbers in 1961. It was stated, in clause 7, that ‘Mr John W. Lennon is authorized as the Group’s representative to receive the payments’.

Armed with documents such as these, and by looking at the record books of the various clubs, I decided that the Beatles had done three Hamburg tours. (John said two – Paul thought four. George wasn’t sure.) I felt all the time that I might have the order wrong and that people would appear with proof that I had put the Beatles in the wrong place at the wrong time.

I am still prepared to admit errors in some of the Hamburg dates. Does it matter? Well, at the time I wasn’t

too

worried, thinking that nobody else apart from me would ever be bothered with such apparently minor details. Since then, of course, scores of researchers have been back to Hamburg, digging over the old embers, including a Dr Tony Waine of Lancaster University, who has made a special study of the Beatles in Hamburg, writing about them for academic magazines, in Britain and Germany. Beatle students never cease to amaze me.

The highlight of my Hamburg trip was meeting Astrid Kirchherr. She helped so much with facts and memories of their Hamburg days and was also the first person I had met who had a clear insight into their different personalities and talents.

Astrid, and her little group of Hamburg art school friends, were the Beatles’ earliest intellectual fans. Until then, and for many years later, they were mainly appreciated by shop girls and

hairdressers, or taken up briefly by low-grade would-be managers, hoping to make some quick money out of getting them a few bookings. Astrid saw something else in them, during 1960–62, which until then no one else had seen, though it was of course Stuart Sutcliffe who she admired most of all and to whom she got engaged.

I was rather shocked by the life she was now leading in 1967. For a start, her room in the house she still shared with her mother was almost a shrine. Like Miss Havisham in

Great Expectations

, she kept it untouched, as it had been in the last few months of Stu’s life. Everything was black, the bed, the soft furnishings, the furniture, and the only light came from some candles. It was very eerie and strange, though she herself was calm and controlled, able to talk about Stu and the Beatles without pathos or melodrama.

In 1963, when Beatlemania first began, she gave some interviews to the German press and others. ‘I was so happy they were doing well that I wanted to help them. I did my best to see the newspapers got the right facts. The papers at first were full of them being four scruffy blokes who lived in a dirty attic in Liverpool. I wanted them to know how intelligent and talented they were. It never came out the way I told them. Over and over again in all the interviews there were the same questions; did you really invent the Beatle hairstyle?’

Now, she’d stopped giving any interviews. She’d also refused offers to do her life story, although the German magazines had been asking her for years. She’d also turned down a lot of money for a tape recording she has, which Stu gave her, of Stu and John and the others playing in the Art School in Liverpool. (Done on the tape recorder that John persuaded the college to buy, for his own personal use.)

‘One record company offered me 30,000 marks for it and I said no. Then they said 50,000. I said no, not for 100,000 or any money. They wanted to put the name Beatles on it and make a lot of money. It wouldn’t have done them any good. They were having a laugh, playing around.’

She said she had never made a penny from all the Beatle photographs she took, even the one of the five of them taken in the Hamburg railway station, which went round the world. She gave that and others to them, long before they were famous. In turn, while they were still un-famous, the Beatles gave them to someone who gave them to an agency. Not only did her photographs make a lot of money for others, she set a style in taking their photographs – half in the shadows – which was copied by other photographers and other groups.

‘The trouble is I never kept the negatives, so I can’t really prove they were mine. Oh, I did get some money once from Brian, for a pile I had given to the boys. He paid me £30.’

She did, of course, get many commissions, on the strength of having taken the Beatle photographs. One famous German magazine commissioned her to take the boys, when they were refusing everyone else, if she could also take along one of their photographers, just to help. ‘John said I should agree. I might as well make some money out of it for a change. This other photographer took some nasty pictures of them, when he shouldn’t have done. They used all his.’

In 1967, when I met her, she was still in contact with the Beatles and John had come to see her when he was in Germany filming

How I Won the War

.

‘John is an original. New ideas just come to him. Paul has great originality, but he’s also an arranger. He can get things done, which John can’t, or can’t be bothered trying.

‘They do need, and they don’t need, each other. Either is true. Paul is as talented a composer as John. They would easily have done well on their own.

‘The most amazing thing about them is that by coming together they haven’t become the same, they haven’t been influenced by each other. They’re each still different, each is still himself. Paul still does sweet music, like “Michelle”, that sort of melody. John writes bumpy music. Working so long together hasn’t rubbed out the differences, which I think is amazing.

‘Now and again at first I did used to wonder if they really cared about people’s feelings and people’s friendship. They would say awful things in front of people – “I wish that Kraut would go away,” that sort of thing. They can still be cruel to people they don’t like, tell them to go away, we don’t like you. But that isn’t too bad. It’s worse to pretend you do like someone.

‘After Stu died, they were so kind and lovely. I knew then they weren’t cruel. It showed me they did know when they went too far and knew when to stop.’

Although Astrid gave so much to the Beatles, which they all acknowledged, in some ways they had wrecked her life. The death of Stu was still obviously very near to her in 1967, though when I met her she had recently got married to another Liverpool exile. The disillusionment with the German press had led her, at the time, to giving up her own career as a photographer.

She was working at the time in a bar, and that evening, after we had talked all day, she took me to it. Hamburg is full of strange clubs and bars, but this was the first lesbian bar I had been into. She got me in, as a friend, and it seemed to be full of prostitutes dancing together, before going off for their evening’s work. Astrid was serving behind the bar and was also on call to dance with customers, if required. For this, working all night long, she was getting £40 a week. Yet she was sitting on a small fortune with all her Beatles memorabilia.

I told Paul all about her when I got back to London and it brought back memories of the good times they had in Hamburg. Paul admitted, looking back, that they were rotten to Stu. He had perhaps been jealous of John’s admiration for Stu and sometimes felt a little bit excluded.

‘I was pretty nasty to him on the last day. We were leaving Hamburg, and he was staying behind with Astrid. I caught his eye on stage, as he was playing with us for the last time. He was crying. It was one of those feelings, when you’re suddenly very close to someone.’

It took me a long time to realize that Brian Epstein was homosexual. When I did, I thought at first it didn’t matter, either way, but I slowly recognized it was a vital part of his character and of his relationship with the Beatles.

Brian Epstein loved them. When at last I spent some time with him, and managed to get him to sit down and think back to the early days, it was hard to stop him. He gave me copies of his old memos to them, which he had typed himself, telling them how to behave on stage and not to smoke or chew. He also gave me his old typewritten list of their early local engagements, which I had no room for in the book, though they might be of interest to Beatle experts. Whole books have subsequently been written on what the Beatles did each day during their Beatlemania years.

Even more interesting is the note, monogrammed BE, that he sent to George Martin before their first recording session on 6 June 1962, suggesting likely songs they might do. Now I look at that list again, there are some compositions I have never heard of, such as ‘Pinwheel Twist’. I wonder what happened to that one?

He also dug out for me the very first press handout about the Beatles and the office memos he sent to his staff when NEMS, his company, opened its first office in London. It’s full of Brian telling them how to behave and to be courteous to everyone. Very typical.

I collected as many documents as I could during all my interviews, as well as handouts and fan club bulletins, both in Britain and in the USA. Brian himself had spare copies of many of them and gave them to me.

He was terribly careful and organized in those early days. It was only as I got to know him better, during 1967, that I learned what a mess his life was now in. He was constantly in the depths of depression, living on pills, having tantrums with his staff and closest friends, over petty things, then collapsing in tears as he apologized to them. He had twice tried to commit suicide, though this had been kept quiet at the time.

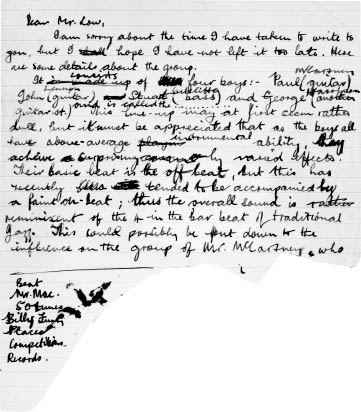

Paul’s early handwritten letter to an unknown journalist called Mr Low, seeking some publicity for the group.

Paul’s early handwritten letter to an unknown journalist called Mr Low, seeking some publicity for the group.In his sexual life, he was not simply a homosexual, but a masochist, deliberately picking up non-homosexual boys, often sailors, bringing them back to the house, treating them, giving them drinks and drugs. It usually ended with him being beaten up and his possessions stolen, very often Beatle material. Then he would be blackmailed, and end up in further depressions.

I spent one weekend with him at his country home in Kingsley Hill, Sussex. On Saturday evening, we had a very enjoyable dinner, at which we were joined by a well-known pop music personality of the time. (Even better known today, but I better not name him.) After the meal, they decided they would like some boys to amuse them, but it was by this time eleven o’clock, and a Saturday evening.

Brian got out a sort of credit card, which was his membership to some homosexual call-boy organization, and dialled a certain number, giving his name and number. There was a lot of discussion on the phone, with the person at the other end saying it was far too late, everyone was booked up, the best boys had gone. When Brian mentioned he was in Sussex, not London, the voice said that was it, no chance. Brian said he would pay for taxis, and pay double the rates, just send down whatever could be found, then he hung up.

I sat up with them, drinking, until midnight, but then I went to bed. I think it was four in the morning before anyone arrived from London. Next morning, I had breakfast on my own, and left for home about midday. The others were still in bed.

Brian agreed I could mention his homosexuality in the book, though, naturally, I was not going to go into any of the details.

The Beatles did not know the full story of this side of his life either. By the time I got to know him, he had become less of an influence on their lives anyway. Paul was busy taking over the organizational reins, setting up Apple, taking control of things like the cover for

Sergeant Pepper

.