Authors: Rick Perlstein

Before the Storm (79 page)

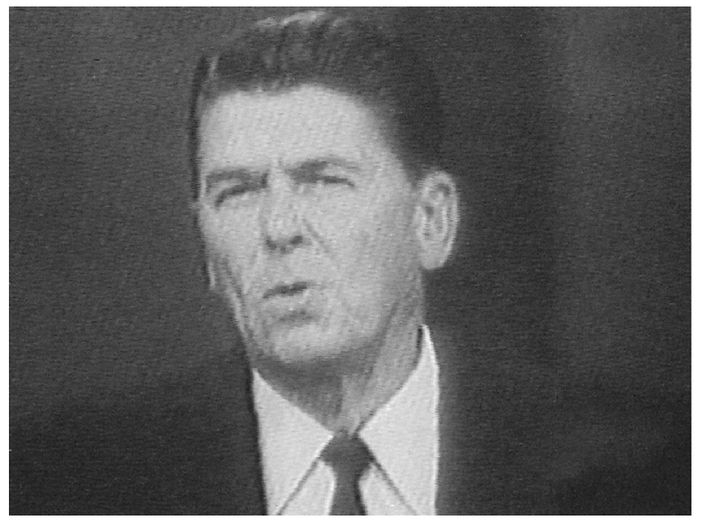

It was Ronald Reagan who inherited the energies left over from the campaign with a last-minute televised campaign speech for Goldwater that commentators called “the most successful nationalpolitical debut since William Jennings Bryan electrified the 1896 Democratic Convention with the âCross of Gold' speech.” Conservatives had finally found a leader who could take them to the White House.

Hamer had emerged as a natural leader of the courageous band of civil rights activists who planned to travel to Atlantic City to issue a credentials challenge to the regularâGoldwaterite, segregationistâMississippi delegation. Seat the MFDP and lose the South, seat the regular Democrats and lose loyalty in the North: the dilemma cut to Lyndon Johnson's paranoid coreâfor surely if he showed any weakness in the face of the dilemma, that would be RFK's chance to humiliate him. On July 31 Johnson instructed an aide to relay one of an endless gauntlet of sadistic tests of loyalty to his presumptive vice-presidential choice, Hubert Humphrey: “Put a stop to this hell-raising so we don't throw out fifteen states.” Two weeks later the President reached Walter Reuther. He listed the governors who were abandoning him, a Shakespearean tragic hero reciting his own dénouement: “Now today Louisiana takes her name off the ballot. Now Arkansas is on his way down to New Orleans to meet with Alabama and Mississippi and Louisiana, and they'll wind up with some serious problems. And this thing is just like a prairie fire. It spreads, and spreads fast.”

“This thing's coming to pieces,” Johnson moaned. “We're gonna have as much trouble as they had in San Francisco unless some of you can, canâ”

He paused and sized up Reuther. It was the quintessence of his method: pinpoint his interlocutor's worst fear, then describe it coming true unless he did his President's bidding. Reuther's, Johnson realized, was the fear that his bitterestfoeâthey had hated each other since 1955âwould ride the backlash to become a blue-collar beau ideal. “They all frighten me half to death what they say he's got in the UAW and the Steelworkers,” Johnson whispered conspiratorially (his reference was to what the Steelworkers' David McDonald had told him at a recent White House dinner about a private poll of the membership showing Goldwater leading). His prey cornered, LBJ moved in for the kill. The MFDP's strategist was Joe Rauh, a bow-tied, bespectacled liberal D.C. lawyer. He was also chief counsel to Walter Reuther's United Auto Workers. “Now, Joe's been on television two or three times....”

The President didn't have to say the rest. The order was plain: Deliver an ultimatum to Rauh to cease and desist or lose his practice's most lucrative client.

Like every Democratic Convention since 1940, the 1964 event was choreographed by Atlanta broadcast executive Leonard Reinsch. Reinsch knew TV. The convention would field only one session a day, at 8:30 p.m.âtypically little

beyond three speakers, a half-hour film, and entertainment by the likes of Peter, Paul and Mary. (The Republican Convention had featured afternoon and evening sessions, endless parliamentary tedium, and upwards of a dozen speakers a day; at one point, an interminable stretch of airtime was taken up with calling Congressman Halleck to the podiumâhe was bending his elbow at a barâso he could introduce General Eisenhower.) Reinsch was desperate to keep the Democratic Convention entertaining; he was desperate to keep tension off the air. Atlantic City had been picked over Miami in the summer of 1963 out of fear of the civil rights rumblings in the South. That was well before this new terror. Blacks had rioted within the past two weeks in nearby Elizabeth and Patersonâabout 90 miles away, like Cuba. Civil rights leaders had promised pickets “so long and black that they would think it was midnight in midday”âenough “to block every entrance into the convention hall.”

beyond three speakers, a half-hour film, and entertainment by the likes of Peter, Paul and Mary. (The Republican Convention had featured afternoon and evening sessions, endless parliamentary tedium, and upwards of a dozen speakers a day; at one point, an interminable stretch of airtime was taken up with calling Congressman Halleck to the podiumâhe was bending his elbow at a barâso he could introduce General Eisenhower.) Reinsch was desperate to keep the Democratic Convention entertaining; he was desperate to keep tension off the air. Atlantic City had been picked over Miami in the summer of 1963 out of fear of the civil rights rumblings in the South. That was well before this new terror. Blacks had rioted within the past two weeks in nearby Elizabeth and Patersonâabout 90 miles away, like Cuba. Civil rights leaders had promised pickets “so long and black that they would think it was midnight in midday”âenough “to block every entrance into the convention hall.”

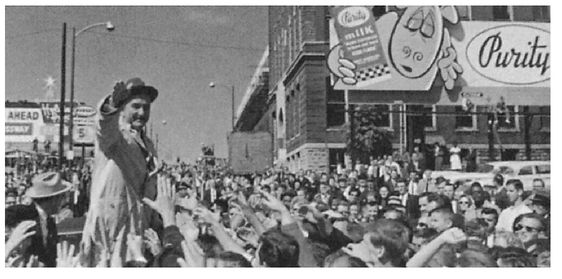

The FBI sent a complement of twenty-seven agents, commanded by Deke DeLoach, the Bureau's second-in-command, answering to the President's top two men, Walter Jenkins and Bill Moyers (the former seminarian's code name was “Bishop”). But with six thousand media personnel on the prowl, and since the networks had invested millions to transport their elaborate temporary studios clear across the country to Atlantic City (CBS judging the stakes so high that the network replaced an incensed Walter Cronkite as commentator, since he had put people to sleep in San Francisco), it was unlikely that anything could keep tension off the air. The Beatles had just began the last leg of their American tour, at the Cow Palace. That was symbolic. Nineteen sixty-four was the year of the screaming crowd.

The Republicans erected a gargantuan eighty-foot Goldwater billboard on the boardwalk directly across from Atlantic City's Convention Hall. It featured the campaign's new sloganâ“In Your Heart You Know He's Right.” (Soon a placard was placed above it, reading “YES, EXTREME RIGHT.” The sign painter had been hired by FCC chair Newton Minow, the scold best known for attempting to elevate the taste level of television by decrying it as “a vast wasteland.”) The words sounded an abiding Goldwater theme. After Goldwater had said back in January that the reason most people were on relief was because they were stupid or lazy, he had explained on the Today show that when he asked those who criticized him if they thought what he said was right, they invariably responded, “Oh, yes, you're right, but you shouldn't say it.” In the

Der Spiegel

interview, he said that if the civil rights vote had been taken in the Senate with the doors locked and the lights off, it wouldn't have gotten even twenty-five senators' support. The billboard seemed a sly reminder of the secretness of the secret ballot: behind that curtain, no one needed to know you thought the blacks were getting out of hand, too.

Der Spiegel

interview, he said that if the civil rights vote had been taken in the Senate with the doors locked and the lights off, it wouldn't have gotten even twenty-five senators' support. The billboard seemed a sly reminder of the secretness of the secret ballot: behind that curtain, no one needed to know you thought the blacks were getting out of hand, too.

The Sunday before the convention, the White House released the latest in a stream of Panglossian press releases: The President's economy drive had eliminated 624 unnecessary government publications for a savings of $2.8 million annually; 11 percent of Americans had owned air conditioners in 1960 but now air conditioners were owned by 26 percent, and during the same period TV ownership had grown from 86 percent to 91 percent. It couldn't camouflage the bad news. He had invited the thirty-four Democratic governors to the White House. Louisiana, Arkansas, Mississippi, and Alabama had stood him up. As the thirty met, Fannie Lou Hamer stepped up before the platform committeeâand the television camerasâand slowly, calmly, told the story of the beatings she had suffered for trying to exercise the franchise a year before. There were two Negro prisoners in the cell with her, she was explaining eight minutes into her testimony. “The policeman ordered the first Negro to take the blackjackâ”

At which point the broadcast broke away. There was word of breaking news at the White House, presumably the long-awaited announcement of Johnson's vice-presidential choice. Instead of Mrs. Hamer's gut-wrenching exhortation, the nation heard Governor Connally of Texas telling reporters what a delightful meeting he and his fellow governors had just enjoyed. But Johnson's gambit backfired. Deprived of Mrs. Hamer's testimony in the afternoon, a much larger audience watched it on newscasts in the evening, full to its aching conclusion: “If the Freedom Democratic Party is not seated,” she pronounced, “I question America.”

There followed over the next few days a bramble of proposals and counterproposals regarding the MFDP's participation at the convention, bullying and cajoling, moral witnessing, wheeling and dealing; and since there was certainly nothing else at Lyndon Johnson's coronation worth paying attention to, the story was followed on TV. Which was enough to send the President, pacing the White House lawn, into the worst funk of his life. Perhaps he knew something about Fannie Hamer's story. The Justice Department had brought a strong case against Mrs. Hamer's tormentors in 1963. They were acquitted by a local jury in a courtroom full of Confederate flags. The reason they were being tried by a local jury was because Johnson had brokered a compromise to get the Civil Rights Acts of 1957 and 1960 past Southern obstructionists: the Justice Department could sue, but federal courts could not preside.

Long since then Johnson had converted to a civil rights crusade more fervent than any President's since Lincoln. And what had that brought? Race riots, two weeks after the Civil Rights Act was signed. What more could he do? “If you give 'em jobs and education, you stop all of it,” he told Hubert Humphrey, sounding as if he were trying to convince himself. The night Hamer

came on TV, Johnson drafted a statement of withdrawal: “The times require leadership about which there is no doubt and a voice that men of all parties and men of all sections and men of all color can and will follow. I have learned after trying very hard that I am not that voice, or that leader. Therefore I shall carry forward with your help until the new President is sworn in next January, and then I will go back home as I've wanted to since the day I took this job.” His wife, and the thought of Barry Goldwater in the White House, convinced him to tear it up.

came on TV, Johnson drafted a statement of withdrawal: “The times require leadership about which there is no doubt and a voice that men of all parties and men of all sections and men of all color can and will follow. I have learned after trying very hard that I am not that voice, or that leader. Therefore I shall carry forward with your help until the new President is sworn in next January, and then I will go back home as I've wanted to since the day I took this job.” His wife, and the thought of Barry Goldwater in the White House, convinced him to tear it up.

Other books

His Primary Desire (New Adult Billionaire BBW Romance) by Jack, Kylie

Guardian of the Hellmouth by Greenlee, A.C.

Crime on My Hands by George Sanders

To Sin with Scandal by Tamara Gill

Walking in the Shadows by Giovanni, Cassandra

Anarchy of the Heart by Max Sebastian

Intercept by Patrick Robinson

Come Back To Me by C.D. Taylor

The Cold Cold Sea by Linda Huber

Manhattan Loverboy by Arthur Nersesian