Belching Out the Devil (29 page)

Read Belching Out the Devil Online

Authors: Mark Thomas

âHow long is the queue?'

âIt is as crowded as it is now.' Which is very crowded. âA lot of women end up with bruises. The children end up fighting.'

This is quite common as others confirm. A second woman in a green skirt joins in, telling of how she and her son go to collect water in the morning. âSometimes we end up fighting.' To avoid this her son âgoes on a bicycle to a different place to get waterâ¦it's very far away.'

Â

Women and children are literally fighting for the remaining water.

Â

Over a series of questions and curt answers The Stare explains she has to draw water for fifteen people in her extended family and five cattle. Then she makes breakfast, walks the three to four kilometres to work, fetching stones from eight in the morning until five in the evening. When she gets home there is no water. âI have to fill water in the evening. By ten o'clock we have our meal.'

Â

One of the kids, maybe five or six years old, takes her hand and looks up at her. The Stare has let her headscarf fall from her face and has tossed it over her shoulder.

Â

âIt's because of the shortage of water that my child looks like this. I don't even get time to bathe them.' She says pulling at her daughter's jumper to show that there is neither water nor time to wash their clothes.

Â

This is not the only impact on the children either, the woman in a green skirt says. âWe have four daughters and one son. All of them have stopped going to school because of the water.'

Â

Because both parents are out working the children have to fetch the water and the shortage means they don't have time to get water and go to school. Green Skirt's youngest daughter Neetu is eight years old and she appears on cue.

âNamaste,' I say to Neetu.

Embarrassed at having been spoken to she tucks herself into her mother's skirt and then peaks from the folds to flash a grin Hallmark could sell a million cards on.

Â

âWhen there is no water she stays back,' says her mother, one hand around Neetu. Her son is a few metres away and she nods towards him. âBecause of water, even our son has stopped going to school. If there is water he will go to school tomorrow.'

Â

So the women get up early, fight for water, have no time to bathe their kids and the children are taken out of school so they can get water for the family. What was it like before the Coca-Cola plant came? A voice from the crowd responds, âThere was a lot of water then.'

âSo do you ever buy water?'

âWe don't have money to buy water,' says The Stare.

The voice from the crowd calls back, âNo, we never bought water before.'

âThen, there was so much water here,' says The Stare and with that she tugs her headscarf firmly over her face and moves away.

Â

A group of men stand by the collapsed Coca-Cola well, the older ones are in their late twenties, the younger ones are barely out of their teens and some are clearly not. They lounge with easy familiarity, leaning on each other's shoulders and dangling their arms around a friend: a vision of a stage gang in a West End musical. They all clearly have something on their minds, though it might be a dance rendition of âGreased Lightning'. They lazily follow our activities and as the women walk away a male voice calls. âWorkers are always crying for employment. They are not given any jobs. Coke gives them employment.' This is no defiant cry, this is a sad statement of fact.

So I ask, âIs there anyone who works for Coke?'

Nudges and looks are exchanged and then, âYes, I have,' says a young man.

âYes,' adds another.

âI worked for three years,' says a confident voice. He's in his early twenties with swept-back hair and in a thin jumper with equally thin stripes. He stands in the middle of the group, framed by two lads behind one resting on each of his shoulders. The confident voice belongs to Rahis, he worked at the bottling plant, though he was employed as a casual worker by the contractor.

âThey never made us permanent. One day you are working the next day you don't have a job. It is not just me. They do this to everyone.'

Â

The group don't say a word but nod quietly as Rahis continues, âSometimes they take us, sometimes they don't. At times they remove us from the job. We are all troubled by this.' He says, indicating the crowd around him.

âHow do you know if you have work that day?'

âAt times they give us a phone call. Sometimes we go and stand in front of the gate. They chase us away, asking us to come the next day.'

Â

It is a relatively common complaint of the temporary worker that the contractor holds out the promise of a permanent job if they do longer hours. And by Rahis's account this plant is no exception. âThey used to always say that we would be made permanent. They used to tempt us and make us work even harder.'

Â

This time the nods are more emphatic. It dawns on me that they all seem to have some experience of working there, so I ask if there are any more Coke workers in the crowd. They

nod and put their hands up. About eight have worked at the plant at one time or another, though some like Rahis no longer do so.

nod and put their hands up. About eight have worked at the plant at one time or another, though some like Rahis no longer do so.

âHas anyone got a permanent job?'

The âNo' that comes from the crowd is more confident now and the youngest-looking of the group pipes up, âWhen the contractors are in need of workers, they make all kinds of promises,' he says, â they promise but they chase the workers away after a while.'

Â

The cocky member of the group is a young lad in a vest with chains around his neck and an Elvis mini-quiff. He stands leaning on his mate's shoulder, who is the drabber of the two in a plain brownish shirt and a scruffy mop top. They look to be best friends. Elvis Quiff nudges Best Friend, and says something to the group who burst out laughing. Best Friend drops his head, when he lifts it up a moment later his face has reddened, this proves even more hilarious to the group who laugh even louder. Best Friend laughs too and shrugs; Elvis Quiff pats him on the shoulder. It is obvious they are somewhat of a double act.

Â

Amit explains to me that Elvis Quiff had told the story of how his best friend had been working in the water treatment plant - this is where the water is purified and cleaned ready to be used in drink production. Best Friend had passed out with the fumes of the chlorine, this, Elvis Quiff had joked, was because Best Friend was weak-brained, thus prompting the laughter and minor moment of shame. But when they stop giggling others acknowledge they have suffered too.

âWhile you were working was a lot of chlorine fumes emitted?'

âYes, in huge amounts.' says Best Friend âThey never did anything for our safety. If people from audit came over they

would give us something for our safety just to show them and took it back when they left'

would give us something for our safety just to show them and took it back when they left'

âWhat did they give you?'

âSafety clothing.'

âWhat kind of safety clothing did they give you?'

âSomething to cover our face,' reports Best Friend.

âMasks?'

âGas masks,' says Elvis Quiff joining his friend.

âGas mask. Gloves,' adds Best Friend.

âCould you describe the masks?'

âThere were strings to tie it to the back of the head...but this was only to show them they never did give us these masks.'

âWhat did they make you do?'

âThey gave us chlorine,' shrugs Best Friend.

âThey used to give us chlorine,' Says Elvis Quiff backing him up.

âThere were people to give us instructions and we used to do accordinglyâ¦they used to tell is what to do.'

âWhat did they chlorine look like?'

âIt looked like white powder, it came in sacks,' explains Best friend.

âPlastic sacks,' says Elvis Quiff, who for some reason, probably mischief, points to the boy who looks like the youngest in the group and says âHe still works for Coke, he still works in Water Treatment.'

âYes,' Youngest says looking at the ground and holding his folded arms high to his chest.

âDo you mix chlorine with water?'

âYes,' Youngest replies.

He is a temporary worker like all of them and he gets 86 rupees for an eight-hour day.

âDid they give you anything for safety?'

âThey have only given us this T-shirt,' Youngest scoffs lightly, indicating the dark blue collared T-shirt he is wearing.

âYes, just a T-shirt,' joins in Elvis Quiff, âShow him your T-shirt'

âNo,' says Youngest giggling and hunching, pulling his arms to him covering something on the breast of his shirt.

âIt's a Coke shirt,' laughs Elvis Quiff and one of the group playfully pulls Youngest's arm away to revel the Coca-Cola logo on his shirt, the shirt that will protect him from the chlorine fumes. And they laugh.

Â

With this I sense they have said what they wanted to, so I ask one final question. âWhen you are working, when you see the result of what Coca-Cola does, when you see the water going here. Does that make you feel conflicted?'

âIt is necessary to fill our stomachs. We have no choice. We need to meet the expenses of our family,' says Youngest.

âIf we don't go, they will bring workers from other villages,' Best Friend states with a shrug, and for once Elvis Quiff doesn't chime in.

So the men will line up outside the gates waiting for a chance to work in the chlorine fumes for a company which is pumping millions of litres of water out of the ground while the women fight each other for pots of water and the children are taken out of school. Like Coca-Cola's well this village is falling in on itself as the water runs out. The question that keeps recurring is the simple one, why did Coca-Cola set up in a drought-prone area? Surely when the company conducted its environmental assessments before opening up a plant, problems with water levels would have been identified? Surely any report would have shown that there was not enough water for them and the community? Exactly why the company chose to open there is a mystery. Who knows, perhaps it was the result of drunken chief executives playing dares: Exxon had to

spill oil on the Alaskan coast, Enron had to turn the lights out in California and Coca-Cola had to open up in the worst possible place for bottling their product.

spill oil on the Alaskan coast, Enron had to turn the lights out in California and Coca-Cola had to open up in the worst possible place for bottling their product.

Â

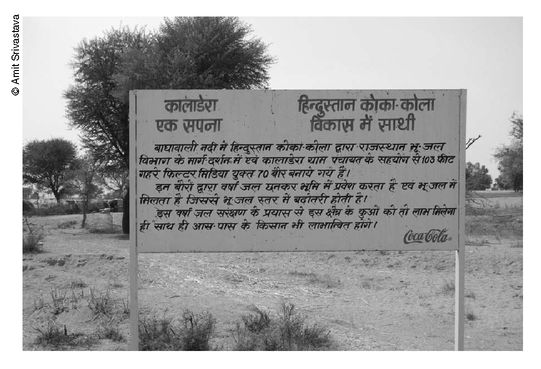

While no one but Coke knows the full reasons why they built their plant in Kaladera, we do know two key facts thanks to Coke's own report by The Energy and Resource Institute (TERI). Unsurprisingly, as they were conducting an assessment of Coke's plants, the organisation asked to see various documents, including the Environmental Due Diligence reports for the plant. These would show Coke's appraisal of the water situation before starting production and might shine a light on how the company thought they could operate in India's driest state. Stunningly, Coca-Cola simply refused to hand them over, âdue to reasons of legal and strategic confidentiality'

4

thus denying the assessors vital data with which to complete their work. But TERI did manage to elicit one vital piece of information. The TERI report states âin response to queries from TERI, Coca-Cola representatives explained that the company's requirements do not explicitly necessitate the assessment of the effects of HCCBPL, Kaladera, bottling operations on groundwater in the region of operation but focused on ensuring a sustained supply of water for business operations.'

5

4

thus denying the assessors vital data with which to complete their work. But TERI did manage to elicit one vital piece of information. The TERI report states âin response to queries from TERI, Coca-Cola representatives explained that the company's requirements do not explicitly necessitate the assessment of the effects of HCCBPL, Kaladera, bottling operations on groundwater in the region of operation but focused on ensuring a sustained supply of water for business operations.'

5

Â

TERI describes this situation by saying the âfocus of TCCC⦠is on business continuity - community water issues do not appear to be an integral part of the water resources management practices of TCCC.'

6

6

Â

In lay language this means the company only checked if there was enough water for its own use. Coca-Cola did not consider at any point if there was enough water for the plant

and

the community. They simply didn't give a fuck.

and

the community. They simply didn't give a fuck.

11

THE FIZZ MAN'S BURDEN

Other books

108. An Archangel Called Ivan by Barbara Cartland

Down Under by Bryson, Bill

Close to the Knives by David Wojnarowicz

Always Remember (Memories) by Hart, Emma

Finding Kat by McMahen, Elizabeth

Chloe's Rescue Mission by Dean, Rosie

Remote Control by Jack Heath

Secondhand Horses by Lauraine Snelling

Hot in the Saddle (Heroes in the Saddle Book 1) by Randi Alexander

Passionate About Pizza: Making Great Homemade Pizza by Curtis Ide