Belching Out the Devil (32 page)

Read Belching Out the Devil Online

Authors: Mark Thomas

Â

From what I can see out here I would agree. The place is dilapidated. Frankly, Pompeii looks in better condition and that was buried under volcanic ash. Coke claim they do the maintenance work just before the monsoon.

8

I suppose it doesn't matter what it looks like if it does the job, though at this stage I am convinced of nothing.

8

I suppose it doesn't matter what it looks like if it does the job, though at this stage I am convinced of nothing.

Someone has to know something about the veracity of Coke's claim and that someone might well be Professor Rathore, a Senior Fellow at the Institute of Development Studies in Jaipur, whose data is quoted in the TERI report. The professor specialises in water resource management and the fine academic tradition of vertical filing systems. Stacks of reports, articles, notes and statistics form tall ordered blocks around the room. So prominent are these piles that if ever a map were to be drawn of it, this would be the first study to require contour lines. The walls are covered in hydro porn, pictures of large bodies of water, bare-arsed reservoirs and cheeky lakes. And stuck in one corner a board has term information, phone numbers, timetables and official pronouncements tacked on with drawing pins. I find the room

strangely reassuring, it smacks of the twin pillars of academia: obsession and overwork.

strangely reassuring, it smacks of the twin pillars of academia: obsession and overwork.

Â

The professor sits behind his desk between two more literal pillars. He is somewhere in his fifties, and has (like many Indian men) innate trust in his ink pen's durability and craftsmanship, as it sits neatly in the top pocket of his spotless white shirt. He peers over his glasses before taking them off and exudes the demeanour of an educator, that is an air of quiet and calm exasperation, a man who has had to explain the obvious too many times.

âIt is the rainfall pattern of Rajasthan which is important,' says the professor. âIf the rainfall is low, then the withdrawal is much more than the water that is being recharged through the rainfall. So it's a perpetual depletion of the groundwater.'

Â

This much everyone seems to agree on. What I want to know is can Coke put up to fifteen times the amount of water they use in production back in the ground, so I start to ask my question, âThe company are saying that they are using rainwater harvesting projects to rechargeâ¦'

âIt doesn't work,' he says shaking his head sadly.

âBut,' I begin again, âone of the rainwater harvesting projects which they've got is on a dried riverbed, they've got seventy bore holesâ'

âThat's the wrong thing,' He interrupts flicking his hand dismissively.

âWhy is that the wrong thing?'

âAsk them how many times that river flowed, you will be shocked to know that in a year, in five yearsâ¦OK, I'll have to show you something.' And with that he rummages in a pillar and plucks out a single piece of paper, showing the number of times the Jaipur area has been in drought. These are the figure that shows that the area has been in drought for 47 per cent of the last 106 years.

Jaipur district frequency of occurrence of drought and its intensity since 1901-2006 Number of years district of Jaipur over past 106 years

⢠56 years normal

⢠10 years light drought

⢠17 years moderate drought

⢠12 years serious drought

⢠11 years very serious drought

Source: Professor Rathore, Institute of Development Studies Jaipur

After staring quietly at the piece of paper I look up at his expectant face and say âSo there is not enough rain...'

Â

He affords a brief smile, âThere is no run off,' he says, referring back to the dry riverbed that won't run without rain, âSo you build a structure and it doesn't work. It will work only when there is a run off. OK? That run off only takes place one or two years, and how much is that? Very small, so these rainwater harvesting structures are to bluff people, and the state.'

âAnd it doesn't work because the riverbedâ¦'

âBecause of these reasons: the rainfall is very meagre; rainy days are very limited; droughts are a perpetual phenomenon, and where is the run off? Where is recharge? Where's the water going to come from?'

Â

The professor makes the simple point that you can't do rainwater harvesting without rainwater. But I still can't quite

believe Coke's credibility rests solely on this, so I try and sneak in one more attempt. âIs there a way the company could do rainwater harvesting in a meaningful way in the area?'

believe Coke's credibility rests solely on this, so I try and sneak in one more attempt. âIs there a way the company could do rainwater harvesting in a meaningful way in the area?'

Â

âNo, it's just not possible, it's not possible.' He holds his hand up and sighs. âCoca-Cola also have a right to do business, we don't contest that but we contest that you can spoil the lives of so many people. You may have Coca-Cola or any brewery industry, but the source of water should not be groundwater, it should be surface water.'

Â

Then looking out from between his two pillars of statistics and reports, unprompted he says, âIf I am chief minister in charge of this, I will stop today the industry, and ship it from that place. I will give them choice. Go to Kota Barrage, go to Indira Gandhi Canal, or quit, there's no other choice. Go to Namada, if you want, but not here, don't have groundwater as your source.'

So I'm left with Coke's claim that âeven in recent years when rainfall has been below average, actual recharge has been more than five times the amount of water used for production of our beverages.'

9

9

Â

I asked Coke if they would show me their figures and assumptions on which they base that claim. After a bit of a wait, they sent me a document compiled by a retired chief engineer that detailed each structure and its expected annual groundwater recharge. And unsurprisingly, it calculates that with normal rainfall the structures can recharge ten times what Coke takes out. In the case of less rainfall, that figure drops to five times. Which is still very impressive, and surely worthy of a little celebration. But before the corks are popped it is worth remembering that these figures are not verifiable.

There are no measuring devices. And around here no one's celebrating. Not the farmers, not Rajendra Singh, not the people who made the river flow again in Alwa and not Professor Rathore. Even TERI say, âWater contingency measures as adopted by the plant seem to rely heavily on rainwater recharge structures, which in turn depend on rainfall in the region. Since the rainfall is scanty, the recharge achieved through such structures is unlikely to be meaningful.'

10

Everyone except Coca-Cola and their retired engineer says, âno rain, no recharge'.

There are no measuring devices. And around here no one's celebrating. Not the farmers, not Rajendra Singh, not the people who made the river flow again in Alwa and not Professor Rathore. Even TERI say, âWater contingency measures as adopted by the plant seem to rely heavily on rainwater recharge structures, which in turn depend on rainfall in the region. Since the rainfall is scanty, the recharge achieved through such structures is unlikely to be meaningful.'

10

Everyone except Coca-Cola and their retired engineer says, âno rain, no recharge'.

Â

Perhaps it's too obvious a solution that maybe Coke could just actually measure the water its collecting, rather than merely âtrying' to do so. So I offer a different solution: if, Coca-Cola, you are so very sure in your historical data and attempted measurements that you harvest so many times more water than you use, why not just use the water you harvest instead of extracting it from the aquifer? You could store your harvested water and extract it at your leisure. Then, when you give back the five, ten or fifteen times more than you need, everyone will see exactly what great guys you are.

Â

I agree with The Coca-Cola Company when they say the âburden of truth is on us', their trouble is no one around here believes them.

P

rofessor Rathore smiles politely and looks at his watch, by way of ending our chat, fortunately I am socially inept so I plough on. âIf it carries on, what will happen, what do you think will happen?'

rofessor Rathore smiles politely and looks at his watch, by way of ending our chat, fortunately I am socially inept so I plough on. âIf it carries on, what will happen, what do you think will happen?'

He raises his eyebrows in concern and says, âVery soon they'll realise that industry has to close. It cannot survive, not

more than four, five years definitely. Because the water quality will deplete, it will be so bad they cannot use it.'

more than four, five years definitely. Because the water quality will deplete, it will be so bad they cannot use it.'

Of all the answers I did not expect, this was about the most unexpected.

âSo you're saying that industry has got four or five years here, and then it's finished?'

âYes, it's definitely finished,' he says stretching slightly.

âWhat happens then to the communities?'

âRuinedâ¦There'll be no drinking water available to them.'

INDIA: A POSTQUEL

W

hen I asked the Hindustan Coca-Cola Beverages Pvt Ltd if I could come and see their plant in Kaladera they refused saying I was âbiased'. I reply using The Coca-Cola Company method of issue resolution and advanced rebuttal techniques.

hen I asked the Hindustan Coca-Cola Beverages Pvt Ltd if I could come and see their plant in Kaladera they refused saying I was âbiased'. I reply using The Coca-Cola Company method of issue resolution and advanced rebuttal techniques.

âWe are proud of the Mark Thomas system of objectivity and are appalled by these unfounded allegations levelled against him. Only recently Mark Thomas became the proud winner of the prestigious Emerald Eagle Award for Unbiased Reporting, the judges cited his even-handed dealing with The Coca-Cola Company as a case in point. But perhaps more importantly Mark Thomas has launched a bold and innovative truth harvesting and trading scheme initiative, where journalists in truth deficit can purchase unused truths on the open market, with exciting possibilities in the expanding markets in truth developing regions of Russia, Italy and the

Daily Express

news desk.

Daily Express

news desk.

âEven in “truth drought” regions he has managed to recharge the equivalent of five times the amount of falsehoods extracted.

âIt is a journey, he is not there yet, but it is one that Mark Thomas is committed to making and he aims to become completely bias neutral by 2011.

âMark Thomas's book will create over 10,000 indirect jobs.'

12

SECOND FATTEST IN THE INFANTS

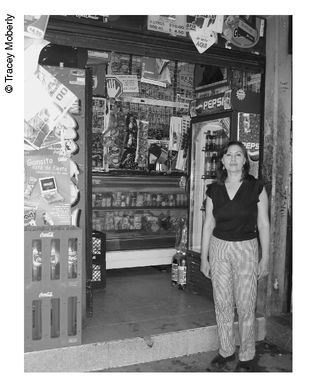

Mexico

âYou know the bottom line is that we welcome competition⦠if the Pepsi company didn't exist we would have to invent themâ¦but we welcome the increased competition because the voice behind the industry is, y'know, a rising tide floats all ships.'

Neville Isdell, The Coca-Cola Company Annual Meeting 2008

Other books

Maigret by Georges Simenon

Chasing Death Metal Dreams by Kaje Harper

Sun Cross 2 - The Magicians Of Night by Hambly, Barbara

MacCallister: The Eagles Legacy: The Killing by William W. Johnstone, J. A. Johnstone

Red Hourglass by Scarlet Risqué

Stricken (The War Scrolls Book 1) by A.K. Morgen

Parker 04 - The Fury by Pinter, Jason

Mine (Dangerous Love Book 1) by Daisy Philips

The Heart of the Phoenix by Brian Knight

Haven: A Trial of Blood and Steel Book Four by Shepherd, Joel