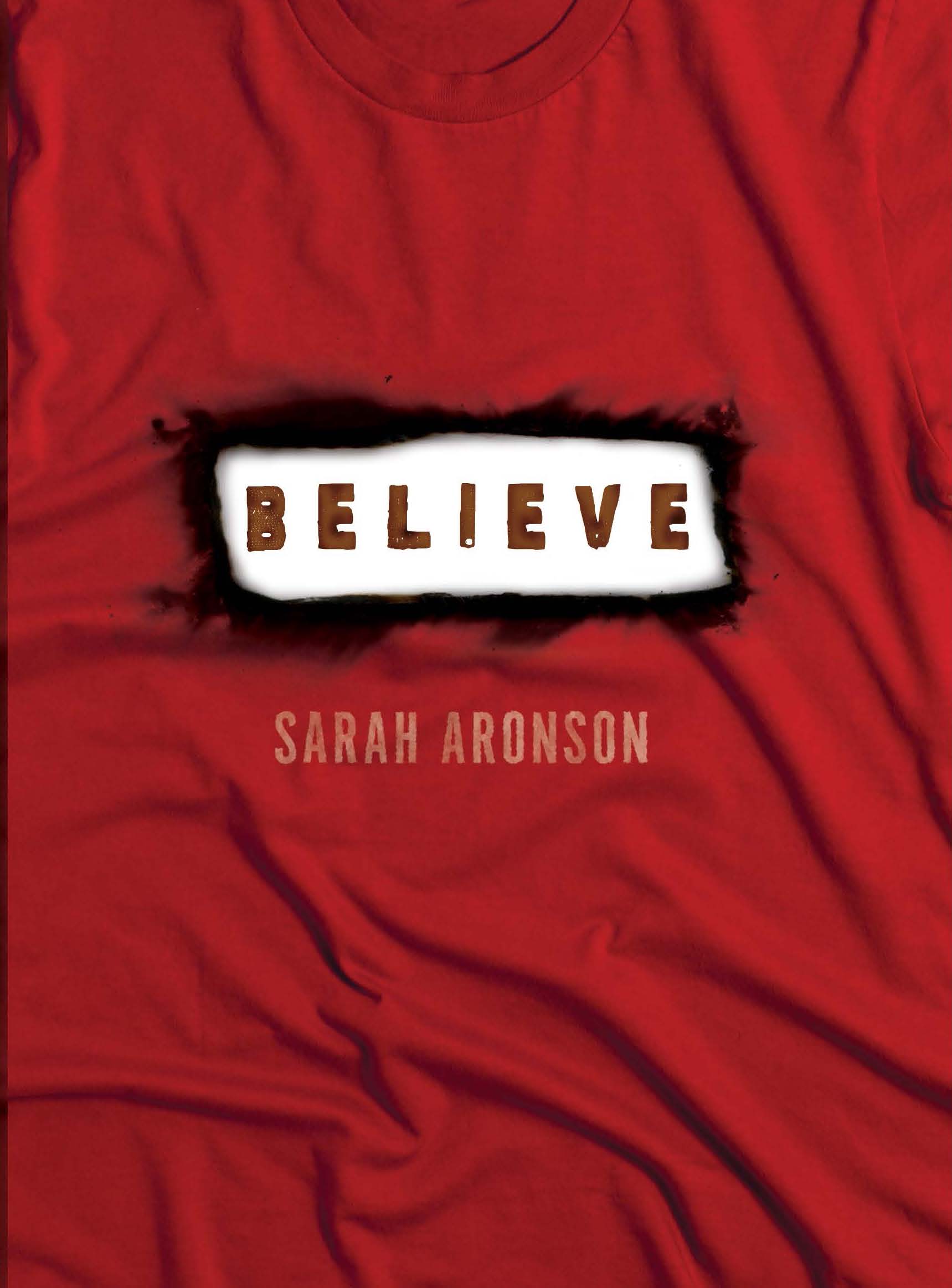

Believe

Authors: Sarah Aronson

When Janine Collins was six years old, she was the only survivor of a suicide bombing that killed her parents and dozens of others. Media coverage instantly turned her into a symbol of hope, peace, faithâof whatever anyone wanted her to be. Now, on the ten-year anniversary of the bombing, reporters are camped outside her house, eager to revisit the story of the “Soul Survivor.”

Janine doesn't want the fameâor the pressureâof being a walking miracle. But the news cycle isn't the only thing standing between her and a normal life. Everyone wants something from her, expects something of her. Even her closest friends are urging her to use her name-recognition for a “worthy cause.” But that's nothing compared to the hopes of Dave Armstrongâthe man who, a decade ago, pulled Janine from the rubble. Now he's a religious leader whose followers believe Janine has healing powers.

The scariest part? They might be right.

If she's the Soul Survivor, what does she owe the people who believe in her? If she's not the Soul Survivor, who is she?

BELIEVE

SARAH ARONSON

Text copyright © 2013 by Sarah Aronson

Carolrhoda Lab⢠is a trademark of Lerner Publishing Group, Inc.

All rights reserved. International copyright secured. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any meansâelectronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwiseâwithout the prior written permission of Lerner Publishing Group, Inc., except for the inclusion of brief quotations in an acknowledged review.

Carolrhoda Labâ¢

An imprint of Carolrhoda Books

A division of Lerner Publishing Group, Inc.

241 First Avenue North

Minneapolis, MN 55401 U.S.A.

Website address:

www.lernerbooks.com

Cover photographs © iStockphoto.com/mattjeacock (shirt);

©

iStockphoto.com/spxChrome

(burn mark).

Main body text set in Janson Text LT Std 10/14.

Typeface provided by Linotype AG.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Aronson, Sarah.

Believe / by Sarah Aronson.

pages cm

Summary: “Janine is the “Soul Survivor,” the girl who, as a small child, was the only survivor of a Palestinian suicide bomb in Israel that killed her parents. Ten years on, she feels like she's public property more than her own person” â Provided by publisher.

ISBN 978â1â4677â0697â1 (trade hard cover : alk. paper)

ISBN 978â1â4677â1617-8 (eBook)

[1. FameâFiction. 2. SurvivalâFiction. 3. TerrorismâFiction.

4. OrphansâFiction. 5. JewsâFiction.] I. Title.

PZ7.A74295Be 2013

[Fic]âdc23

2012047184

Manufactured in the United States of America

1 â BP â 7/15/13

eISBN: 978-1-4677-1617-8 (pdf)

eISBN: 978-1-4677-3381-6 (ePub)

eISBN: 978-1-4677-3382-3 (mobi)

FOR REBECCA

PROLOGUE

You never really knew me.

I was a photo in a magazine, the cover that made you weep. I was long brown hair, big green eyes, and pale skinâan innocent girl, alone in a foreign land.

I was a moment in time. I was a story. Even now, when people hear my name or see my hands, they tell me exactly where they were the day I became a household name. They like to say it is an honor to meet me. More often than not, I made them believe.

Over the years, I have received two hundred and twenty-five teddy bears. I've been invited to participate in four reality shows, and two cable networks will pay my college tuition to make movies about the day Dave Armstrong dug me out of the rubble and saved my life.

Churches and synagogues write to me every year. They want me to talk about hope. And survival. And God and faith and my hands. They all want to talk about my stupid, ugl

y hands.

You may be curious, but the answer is no.

I don't want to make a statement.

I don't want to pose.

I don't even like teddy bears.

It is hard enough being a sixteen-year-old orphan, living with your mother's sister, making everyday decisions like what looks best with black jeans and if the time has come to have sex with your boyfriend. I am nobody's bastion of hope, and I don't want to make money talking about suicide bombers, holy war, or anything else that has to do with the day I became the “Soul Survivor,” America's blessed child, the one and only person to walk away from that Easter weekend bombing in Jerusalem.

Get this straight: I am a victim, not a celebrity. I'm a girlânot that different from any other. My hands do not bear the mark of God. They are not blessed. I like regular things, like making my own clothes and hanging out with my friends. I would rather fade into the woodwork than be famous one more day for something I did not earn or do.

You want the real story? There is none. I am a personânot public property.

ONE

Miriam Haverstraw had beautiful hands.

Long, slender fingers and smooth white skin with absolutely no discoloration, deformity, or any sort of noticeable dysfunction. Her nails were simply perfectâstraight on the top and just the right length, not too long and not too short.

She sat curled up in the window seat and rummaged through her faux leather purse for eco-friendly products, never tested on animals, mostly edible. The window seat was always the most coveted spot in my bedroomâcozy and comfortableâbut she sat there now because it provided a perfect view of the street below.

“Be careful,” I saidâpointing to the open bottle of nonacetone polish remover. I had just finished re-covering the cushion she was sitting on. That stuff might be organic, but when it spilled, it left a stain.

Miriam didn't flinch. “Janine, I hate to tell you, but an old lady just took a picture of your house.”

I wasn't surprised. Every anniversary, all kinds of people banged on my door, hoping for a quote, an interview, or a photo. “Just do me a favor,” I said, taking a break from my work to stretch each of my knuckles, “and don't let her see you.”

My hands were ugly. My palms were scarred, my pale fingers bent off to the sides, and my thick nails cracked and chipped. No matter what oil or cream or fruit extract Miriam swore would work wonders, if I didn't stretch them every day, they stiffened up. Stress did not help. Neither did clenching my fists. Or listening to Miriam give me the play-by-play outside.

“Poor thing's dragging her bag up the driveway. She looks like she's having a really crappy day.”

Most of the reporters who came here were young. This one, according to Miriam, had gray hair. She said, “She looks sort of sweet. Like a grandma. Maybe she's different.”

“Or maybe it's a disguise.” It wouldn't be the first time some “hardnosed” reporter tried to trick me into talking.

Miriam dipped her finger into some cream the color of mud and rubbed it into her cuticles. “It's just that ⦠under the circumstances ⦔

“No.” As far as I was concerned, this was a dead end, a non-conversation. “Can't you see this from my point of view?”

That cream stunk like coffee. “Janine, the farm is in trouble. I'm your best friend. This matters to me. We could really, really use some publicity.” She started to pack up her stuff. “I would do it for you.”

I hated when she begged, when she made me explain (again) why this was not the same kind of favor as getting her an invitation to a party (

that

I would do) or going to some event (which I knew she did all the time, even when it was the kind she found boring). This wasn't a football game. It wasn't a study session or a chance to meet some cute guy. “You know what'll happen. She'll listen and make conversation until you say something you shouldn't. Think about it. She wants a story about me. She doesn't care about your farm.”

Miriam's farm was a two-acre plot stuck next to an old, half-empty nursing home, not too far from school. For as long as I could remember, the town's supervisors had leased it (for one dollar) to a bunch of professors so they could plant vegetables and teach nutrition. She thought it was the most beautiful place in the world. It was an essential part of our town's future sustainability and growth, proof that good people (like herself) could come together and make the world a better placeâa lesson for other small towns to learn from. It had to be protected at all costs.

Personally, I thought it was a piece of landânothing more. It was nice that the town let people plant their vegetables there, but the truth was it didn't even get much sun. But I couldn't tell her thatâespecially not now. The trustees from one of the local colleges had their eyes on that property. They'd already offered the town a whole lot of money plus a bigger farm (but on the outskirts of town) for it. They wanted to build dorms. Or a research lab. Or offices.

Normally, the town's board of supervisors would have jumped at this deal. It was a lot of money. The new farm would be bigger and better. It was smart to work with the college. Winâwin.

But in this case, no deal yet. That was because of the giant oak tree in the corner of the propertyâit was the biggest one for milesâpossibly the oldest in the area. People were crazy about it. When the trustees couldn't promise to protect itâtheir issue was safety (it was a really old tree)âprotests and arguments flared. The newspaper had already run at least ten letters to the editor.

The whole thing annoyed me. Every letter or comment made that tree out to be a symbol for some over-the-top concept like freedom or life or the power of the people. And that was wrong. That kind of talk blew everything out of proportion. It's not like you could argue over something like freedom.

It made me feel sorry for the tree.

But it also made me feel a whole lot less guilty. Because of that tree, the farm was safe. Miriam didn't need to talk to that reporter.

Outside, she rang the doorbell once, then two more times. “Are you sure?” Miriam asked. “Just this once. I'll never ask again. We could really, really ⦔

“No. Finish your toes. I am totally, one hundred percent, absolutely sure.” Miriam put up with a lot from me. But this was too much, too risky; I didn't need this stress. I had more important things to do.

I hunched over my prized possession, my brand-new Brother Quattro. If I was going to finish this dress for my official portfolio, the hem had to come up. The bodice needed a little more bling. Miriam was going to have to stop telling me to come to the window.

“What is it now?” I asked, mid-seam.

“Abe is here. He's talking to the lady.” I stopped sewing and walked over to the window. This was not cool.

He could be telling her anything: what I like to eat, what I do in my free time, that sometimes, for no reason whatsoever, I turned sullen. He could be telling her important stuffâlike how I have a hard time sleeping. Or stupid stuffâthat my aunt, Lo, and I had lived here since I came here from Israel; that my bedroom was in the loft; that last year I'd created a series of silkscreened T-shirts called “A door of one's own.” Because I really wanted my own way out.

I glared at Miriam. If we tried to get his attention, that reporter would figure out we were here. If we didn't â¦

“I thought you told him we were having a girl's day.”

She pressed her nose to the window. “You know he never takes a hint.”

Some days, nothing went right.

When Miriam first introduced me to Abe, I was skeptical. I told her a tripod relied on three strong, equal legs. “I don't believe that guys and girls can ever have completely mutual, platonic relationships,” I'd explained. One person always wanted more than the other.

But he hung around. So, after a while, we made an official pact. Friends only, nothing more, no matter how “right” it felt. No discussion whatsoever about God, faith, or anyone who became famous because of reality TV. I told him that everything I said must be kept absolutely confidentialâno exceptionsâespecially when it came to the press.

I figured he'd balk. Or at least tell me I was unreasonable. But he agreed to everything. Same as Miriam, he said, “That's what friends do. They trust each other completely.” Then he held out his handâa perfectly nice hand the color of caramel, no exfoliation or moisturizer necessary. “You want to prick me? Share blood? Take an oath of brotherhood?”

Now I hoped he meant it.

Now I had to trust him.