Belisarius: The Last Roman General (31 page)

Read Belisarius: The Last Roman General Online

Authors: Ian Hughes

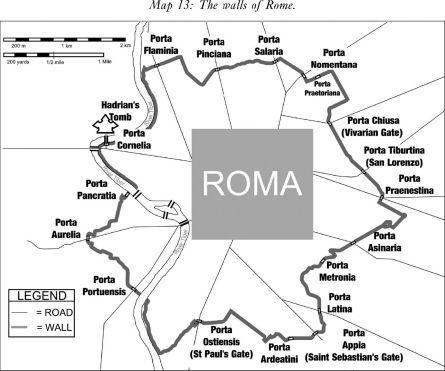

Upon his return, Belisarius had immediately assigned his troops to their duties. He had placed one of his commanders at every gate with a detachment of troops. Bessas was at the Praenestine Gate, and Constantinus was at the Flaminian Gate, where Belisarius ordered a stone wall built inside to ensure that it was secure from attack. Belisarius had taken personal control of the Pincian and the Salarian gates, as these were most suitable as exits from which to launch sallies against the Goths. These four gates faced the Gothic approach and so were most in danger of attack. Belisarius had placed his most reliable officers in charge here. The remaining gates were assigned to his infantry commanders, since they were deemed to be less threatened by the Goths. He further ordered the siting of catapults and stone-throwers on the walls, ready for the expected assault of the Goths.

Shortly after the siege began, Bessas reported a rumour that a number of Goths had broken into the city. Belisarius sent men to investigate and, when they reported that no such thing had happened, he sent an order to all of his commanders ordering them to ignore all such rumours in the future and remain at their posts; Belisarius would deal with any real breakthroughs in person.

Once the Goths had broken the aqueducts, Belisarius took measures to ensure that they were blocked where they entered the city, so that the Goths could not repeat the strategy he had used to gain entry to Naples. However, the aqueducts had provided the power for the mills that ground the city’s flour. Belisarius countered this by suspending water-wheels between two boats, mooring the boats in the Tiber, and using the force of the river to turn the wheels and grind the corn. Although the Goths released logs and other debris upstream in an attempt to destroy the floating mills, Belisarius ordered a chain to be hung across the river and the danger was averted.

As the siege progressed, the citizens began to feel the pressures of a city under siege. They began to share their dissatisfaction with each other and deserters brought the news to Witigis. As a result he attempted to open negotiations with Belisarius, but was rebuffed and the siege continued.

Having completed his preparations, at dawn on the eighteenth day of the siege Witigis launched his assault. Siege towers pulled by oxen, battering rams, and Goths with large numbers of scaling ladders approached the walls. Belisarius ordered his men to hold their fire until he gave the signal. As the Goths came within range, Belisarius fired three arrows at the enemy, each one finding a target. The other defenders now fired their bows at the attackers, but those around Belisarius were ordered to kill the oxen pulling the towers. When this was accomplished, the siege towers lay immobile and useless. The attack stalled. When a Goth was pinned to a tree by an artillery bolt the majority of the Goths withdrew out of range, and a sally by the defenders routed the remaining attackers. The Byzantines set fire to the engines and returned inside the walls. Procopius again inflates the figures and claims that in this assault 30,000 Goths were killed (Proc,

Wars,

V.xxiii.26).

At the same time at the Cornelian gate, which was defended by Constantinus, the topography and the plant cover enable the Goths to reach the walls without being seen. The Byzantine catapults could not fire down at them and the defenders were exposed to danger if they leaned far enough over the walls to aim their bows at the attackers. In desperation, the men on the top of Hadrian’s tomb broke up the statues and hurled them down upon the attackers. The attack was repulsed and, as the Goths withdrew, they came under fire from the artillery on the walls. Similarly, an attack on the Pancratian Gate, held by Paulus, also made no headway.

Strangely, the Flaminian Gate, held by the Reges infantry unit (the descendants of the Regii of the

Notitia Dignitatum)

under the command of Ursicinus, was not attacked at all.

Events at the Porta Chiusa (Vivarium Gate) were different to the others. Here, the original wall had crumbled – possibly due to subsidence – and a section of wall had been added outside this to protect the damaged part. The space between the two walls was known as the Vivarium, as animals were often kept there. A Gothic mine had been dug in order to collapse the outer wall at this point. Bessas and Peranius, who were in control of this area, were hard pressed by the Goths and so sent to Belisarius for help. The arrival of the general restored morale and, taking note of events, Belisarius allowed the Gothic mine to complete its work. When the Goths entered the breach they found themselves faced with another wall. At this point Belisarius ordered Cyprian and his men to attack the Goths in the Vivarium. The Goths panicked and began to flee back through the breach. As the Goths were milling around in confusion at this unexpected setback, Belisarius launched a sortie that routed them and they fled in panic back to their camps. The victorious Byzantines again burned the Gothic siege engines and retired behind the walls.

The first Gothic attempt upon Rome had failed. Belisarius had shown his men that they could defeat the Goths, and had shown the Goths that the capture of Rome would not be as easy as Witigis had led them to believe. Belisarius’ deployment of his troops, his rapid assessment of the situation, and his expert timing of sallies that caught the Goths unawares and resulted in them receiving heavy casualties, must all be applauded; this was a masterpiece of defensive warfare.

In spite of his successes, Belisarius knew that he did not have the forces to raise the siege or win the war. Consequently, he despatched messengers to Justinian requesting reinforcements, informing the emperor that in leaving garrisons in selected strongholds he had been force to reduce the number of available men to only 5,000. Procopius states that, as the Goths had 150,000 men, Belisarius requested reinforcements to bring him up to a parity with Gothic numbers (Proc,

Wars,

V.xxiv.1-9). This is clearly unrealistic, since the emperor did not have that number of troops in the entire imperial army, and is a further example of Procopius’ willingness to exaggerate the numbers of the Goths in order to glorify the achievement of Belisarius. In fact, Justinian had already sent reinforcements. The

foederati

that had served alongside Belisarius in Africa, under Valerian and Martinus, had already been recalled to Constantinople before being dispatched for Italy. Unfortunately, the weather had trapped them in Greece. Belisarius was informed of their impending arrival and waited in Rome for their coming.

Recognising that he did not have enough troops, and that most of the men in the city could not work due to the siege, Belisarius enrolled the citizens to fight alongside the regular troops, paying them wages for their services. Since the men had no other means of income, the measure was a success as it increased Belisarius’ manpower whilst at the same time increasing the loyalty of the citizens to their new commander. It was a brilliant stroke of propaganda.

Witigis

Baulked in his assault upon the city, Witigis decided that his next move would be to seize the Roman harbour at Portus. This is where incoming ships transferred their cargo to smaller boats and barges which then transported the goods upriver to Rome. Three days after the assault, he led his men south and captured Portus on or around 13 March 537, leaving 1,000 men as a garrison. The move increased the difficulties for the defenders. Although the Goths did not surround the city, Rome still had a large population to feed. These had been supplied by river, but with Portus taken supplies had to be landed at the port of Antium, which was near to Portus, taken overland to Ostia – a day’s journey – and then taken overland from Ostia to Rome. Supplies in the city began to decline.

Angered by the treachery of the Roman citizens, Witigis sent orders to Ravenna that the senators earlier taken as hostage should be executed. Rumour of the order arrived early and a few of the senators managed to escape. The rest were killed.

Belisarius

Once he realised that the Goths, although repulsed, were going to maintain the siege, Belisarius sent the women and children to Naples in order to reduce the burden on the food supplies. The rations in the city would now last longer. He would also not need to worry about their safety should the Goths force entry to the city.

Worried about the possibility of treachery, he ordered the guards at the city gates to be rotated frequently in order to minimise their opportunity for betrayal. At night he sent men to camp near to the moat, safe in the knowledge that the Goths had not yet recovered from their defeat and would not attempt an attack on any such forces. These men helped to reduce the possibility of treachery by not allowing the Goths close access to the walls under cover of darkness.

A letter was now discovered, allegedly linking Pope Silverius to a plot to restore the city to the Goths. Forged by Julianus, the

praetorianus,

and Marcus, a

scholasticus,

the letter was given to Belisarius who ordered that Silverius be sent to Lycia. On 29th March Vigilius was ordained as the new Pope, allegedly by the order of Theodora. Justinian later ordered that Silverius be returned to Italy, pending an investigation. Belisarius surrendered him to the custody of Vigilius, whose men starved him to death. Vigilius is said to have promised to give Belisarius 200 pounds of gold for his support; it was not the only hint of scandal linked to Belisarius during the siege.

In a similar manner, Belisarius also ordered that many senators be sent out of the city to forestall any attempts at betrayal. Although the commoners had been recruited into the army and paid, so ensuring their loyalty, the Pope and the senators, being of a higher class, probably declined to take an active part in the defence. Feeling no obligations towards Belisarius, their loyalty was suspect, especially since they had already betrayed the city once before, when they had allowed Belisarius to gain entry.

Belisarius takes the Initiative

Twenty days after the Gothic capture of Portus, and twenty three since the failed assault, so probably around 5 April, Martinus and Valerian finally arrived with their 1,600

foederati.

These cavalrymen were mainly Huns, Slavonians and Slavic Antae – cavalry archers of proven ability. More confident due to the reinforcements, Belisarius decided to adopt a more aggressive stance.

On the following day he instructed one of his bodyguards, by the name of Trajan, to take 200

bucellarii

out of the city via the Salarian Gate to a nearby hill. Once there, the cavalry were to engage the enemy using only their bows, but, when the supply of arrows was exhausted, to retire to the safety of the city. At the same time, Belisarius ordered the catapults on that section of the walls to be made ready to cover the retreat.

Trajan carried out the order, riding to the hill and starting to shoot at the Goths. Disturbed by this new development, the Goths seized the equipment that they had to hand and rushed out of their camps. When all of their arrows were expended the Byzantines began their withdrawal, with the enemy in close pursuit. As they came within range of the walls the catapults began to fire, killing many of the Goths and prompting the rest to immediately abandon the pursuit and retire out of range. In this engagement Procopius claims that the Goths lost 1,000 men killed (

Wars,

V.xxvii. 11), but again the figure has been exaggerated for the benefit of Belisarius. It is unlikely that many Byzantines were casualties, since the Goths had little response to their use of archery.

Four days later, Belisarius repeated the tactic. On this occasion 300

bucellarii

led by Mundilas, another of Belisarius’ bodyguards, caused a greater number of casualties than the original sortie. Finally, after another lapse of a few days, Belisarius repeated the tactic, sending another guardsman, Oilas, again with 300

bucellarii.

In the course of three engagements, Procopius claims that the Byzantines killed around 4,000 men, although doubtless he has distorted the number of Gothic losses.

Witigis

Procopius now describes Witigis’ response to Belisarius’ tactics

(Wars,

V.xxvii. 15-23). Without fully understanding the reasoning behind Belisarius’ ruse, Witigis now attempted a similar stratagem. He sent 500 men to demonstrate near to the city without advancing near enough for them to suffer casualties from the catapults on the walls. Immediately grasping the situation, Belisarius sent 1,000 men under Bessas to engage the Goths. Forced to retire under a hail of Byzantine arrows, the Goths were surrounded and almost annihilated.