Belisarius: The Last Roman General (39 page)

Read Belisarius: The Last Roman General Online

Authors: Ian Hughes

Belisarius, on the other hand, was constantly attempting to take the initiative during the siege of Rome, and managed to achieve it so effectively that Witigis ended being besieged within his own camps. Furthermore, when the war entered its later stages Belisarius attempted to relieve the cities under siege by the Goths and focused upon clearing the approach to Ravenna. The fact that he managed to complete his strategy is a sign of the high quality of his generalship in the war, but we should not exaggerate his achievement: Witigis did not provide him with a high level of opposition, and it is possible that many of Belisarius’ subordinates could have equalled the general’s exploits.

Apart from maintaining the initiative, Belisarius won the war with his realisation that the Goths, like the Vandals, had no answer to his mounted archers, and with his grasp of logistics. Throughout the siege of Rome, and when faced with Goths in the open, he relied upon the abilities of his horse archers to weaken and demoralise the Goths. He succeeded so effectively that the Goths became terrified of their abilities and refused to leave their camps. Furthermore, Witigis later refused to meet him in the open, despite having won the Battle of Rome and shown that in the correct circumstances the Byzantines were extremely vulnerable..

In many ways it was Belisarius’ grasp of logistics that helped him to win the war. He managed to keep Rome supplied during the siege, and understood that, by remaining in their camps, the Goths were leaving themselves as vulnerable as if they were actually the besieged, rather then the besiegers. It is quite possible that many of his actions can be interpreted as ways of reducing his own supply problems, as well as putting pressure upon the Goths.

In the war, he made only three mistakes that proved to be costly. The first was in accepting battle outside Rome. Procopius does his best to lay the blame upon the regular troops, claiming that they pressured Belisarius to fight when he did not want to. Yet later, when the Romans demanded that he fight a second pitched battle, he had the strength of will to refuse. Furthermore, the excuse had already been used at Callinicum in the east, where Belisarius again was allegedly pressed by the troops to accept battle against his better judgement. It is probably safer simply to accept that he made a mistake. The Goths had suffered heavy losses, caused by his policy of using small groups of horse archers in hitand-run tactics. It is easy to understand that he believed that Gothic morale was extremely low and that under pressure they would break; after all, a similar thing had happened at Tricamerum in Africa. He made a mistake and lost the battle. Fortunately, the heroics of Principius and Tarmatus, along with a section of the infantry, allowed the Byzantines to retreat with fewer casualties than they may otherwise have suffered.

His second mistake was to accept the invitation to garrison Milan. The city was too far away from the rest of his forces, and so was vulnerable to attack. Furthermore, it was on the far side of a major river, the Po, and was not easy to either reinforce or relieve when besieged. That said, it is easy to show that the occupation of Milan was a mistake in hindsight: in reality, his detaining the envoys over winter can be interpreted as his being unwilling to make the commitment, and it is probable that he only agreed because of the political implications. Along with Milan he gained control of the area of Liguria, one of the most fertile in Italy. If it was a mistake, it was an understandable mistake.

His third, and perhaps his greatest mistake, was that he rushed the end of the war. It was becoming likely that the envoys sent by Justinian would make arrangements to end the war before Belisarius had completed his military conquest. For whatever reason, whether the pursuit of glory, the desire to simply finish the task, or for some other motive, Belisarius was not prepared to allow the Goths to escape without acknowledging their total defeat. The result was to be disastrous for Rome.

Due to the need for speed, Belisarius failed to comprehend the Gothic fears for their safety and the depth of their desire to remain in Italy: after all, although seen in Constantinople as ‘Germans’ and foreigners imposing their will on the Italian natives, they had been born in Italy and considered themselves to be ‘of Italy’. If Belisarius had taken more time in the negotiations, he may have listened to and understood their fears and taken steps to allay them After all, the majority of Goths had returned to their homes south of the Po, apparently with no intention of restarting the war. With only a little extra patience the war could have been finished before he left.

He did not take the time, and rushed through the peace negotiations. Convinced that Belisarius was going to accept the kingship, and so ensure that they would not be deported to the east, the Goths accepted their defeat. When Belisarius refused to accept the throne, the situation again became unclear, and the Gothic nobles were uncertain as to their future. With his dismissal of their request to become king, Belisarius alienated the Gothic nobles, as his actions may have been perceived as demeaning the kingship. In these circumstances were planted the seeds for the continuance of the war after Belisarius had been recalled.

There is only one note of caution that remains concerning Belisarius’ abilities as a general. He does not appear to have been confident in his use of infantry, instead relying almost wholly on the cavalry. It would be easy to dismiss this by noting that the infantry were obviously of poor quality and had fled from the field at the Battle of Rome with potentially disastrous results.

Yet this is not the whole story. A portion of the infantry, led by Principius and Tarmatus, fought bravely against the Goths. It is clear that, if they had been properly trained by Belisarius and led by officers who did not run away at the first opportunity, they could have formed a valuable asset to the Byzantines, both in attacking enemy fortifications and by acting as a rallying point for the cavalry. By neglecting these troops, Belisarius diminished the fighting strength of his army by disqualifying a section of his troops from taking an effective part in battle.

Despite these reservations, overall the Italian campaign reinforced his reputation and highlighted his military abilities in a way that they had never been shown before, either in Africa or in the east. Now that he was returning to the Persian front, his abilities would be tested against armies that had already shown that he could be beaten. It remained to be seen if his experiences in the west had given him the knowledge and maturity to master the armies of the east.

Chapter 11

The Return to the East

The Reforms of Khusrow

The so-called ‘Eternal Peace’ that was agreed between Rome and Persia following the defeat of Belisarius at Callinicum is commonly attributed to the desire of Justinian to free troops for the upcoming war against the Vandals. Although there is a large amount of truth in this conclusion, Khusrow also appears to have wanted a peace treaty. However, he understood that Justinian was in a rush and so ensured that he gained the best possible terms.

The reason for the desire for peace was that Khusrow was about to set in motion a system of reforms. In Chapter 4 it was shown that the Persian army was effectively a feudal force consisting of lords who were granted land in return for military service. They in turn conscripted men into the army who thus owed their loyalty to the nobles. Khusrow had determined to change this for a professional force with no loyalty to the nobles, only to the king.

To complete these reforms, Khusrow would have to curtail the power of the nobles. To do this, he enrolled the lesser nobility, the

dekhans,

into the

savaran.

This diminished the influence of the upper nobility and allowed his further reforms to pass, since the nobles no longer had the power to stop them. This created a much larger manpower base from which to recruit the

savaran

heavy cavalry. As a by-product, it correspondingly reduced the number of troops available to serve as light cavalry, especially as horse archers. To overcome the shortage, Khusrow began an active recruitment campaign amongst the tribes bordering the empire, aimed especially at recruiting horse archers.

Possibly due to the

dekhans

being unable to afford the expensive equipment needed to serve in the

savaran,

Khusrow instituted a salary for the army and equipped the troops from state arsenals. In effect, Khusrow created a professional fighting force owing loyalty to the king, so further weakening the power and influence of the nobles.

As was shown in the previous disussion, the command of the Persian army was usually left to the

eran-spahbad,

who was traditionally a member of one of the seven most influential families. The post was now abolished. Instead, command devolved upon four

spahbads,

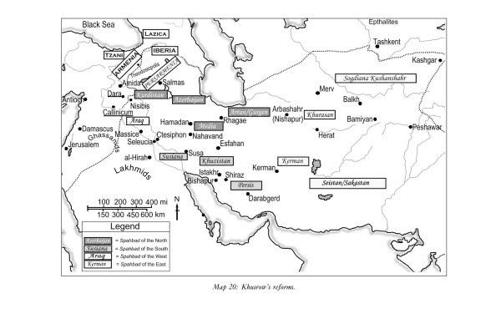

each of whom was given control of a specific region within the empire.

The

spahbad

of the north was responsible for the provinces of Media, Kurdistan, Azerbaijan and Arran, and also the passes over the Caucasus, including the Derbend Pass that had been a bone of contention between the Persians and the Byzantines in the past. The

spahbad

of the east was responsible for the provinces of Khurasan, Seistan and Kerman. The

spahbad

of the south was responsible for the provinces of Persis, Susiana and Khuzistan, including the long coast on the Persian Gulf. Finally, the

spahbad

of the west was responsible for the most important area of all: Mesopotamia (known to the Persians as Araq, ‘the Lowland’ – modern ‘Iraq’). Each

spahbad

was responsible for the recruitment and levying of troops within his designated area, and in theory with ensuring that each of them was armed and equipped in the correct manner.

It was only when these reforms had been completed that Khusrow began to look at the situation regarding the Byzantines in the west.

The Second Persian War

It was obvious that Khusrow was going to invade (the political events leading up to the war have already been covered in Chapter 9). In anticipation of the threat, Justinian divided the eastern command: Belisarius was to be given control of the western portion of the command, Buzes control of the eastern portion, up to the frontier with Persia. Until the arrival of Belisarius, Buzes was given command of the whole.

The First Year: 540

In the spring of 540, Khusrow invaded the Empire. Moving along the west bank of the Euphrates, he bypassed the fortress of Circesium, which was situated on the opposite side, in the angle formed by the junction of the Euphrates and the River Aborras, before arriving at the city of Zenobia. The city refused to surrender, so Khusrow bypassed this city as well and travelled onwards before setting up his camp opposite the city of Sura. Khusrow decided to take the city by storm and in the ensuing attack Arsaces, the commander of the defenders, was killed. As a result, the defenders lost heart and the local bishop was sent to negotiate a surrender. Khusrow decided to appear to be considering the proposal but ordered his troops to follow the bishop as he returned to the fortress and, as he entered, to rush forwards and prevent any closure of the gate. The plan worked, the gate was forced and the city carried by storm. The embassy from Justinian was still accompanying the king as he attacked. They were now released and travelled to Justinian to inform him of the defeat.

Moving forwards, Khusrow sold the captives he had taken to Candidus, the bishop of Sergiopolis, receiving 2

centenaria

(a

centenaria

was 100 pounds of gold, possibly equal to 100,000

sesterces -

a vast sum of money) for the 12,000 captives. Furthermore, if Candidus did not pay the money by a set date he would then be liable to pay double the amount.