Below the Root (14 page)

Authors: Zilpha Keatley Snyder

Fear and revulsion swarmed over him in a strange entanglement with other emotions that felt almost like exhilaration and anticipation.

Neric was watching him curiously. “Have you never thought of being a Priest of the Vine?” he asked. “Of visiting the forest floor?”

“Not really,” Raamo said. “At least I had not really considered that I might someday be visiting the forest floor in a procession of Ol-zhaan, since I truly expected to serve as a healer. But as a child I sometimes climbed down nearly to the floor, and at such times I felt, somehow, that I was drawn there almost against my will—that I was some how destined, or doomed perhaps, to walk there.”

“I, too,” Neric said. “How strange that we should both have felt such an attraction—such an irresistible curiosity. Perhaps—” Stopping in midsentence, he seemed to fall into deep thought.

Raamo, too, was silent, pursuing an idea that had just occurred to him. “Neric,” he said at last. “I’ve been thinking—Genaa has, I know, a deep commitment to finding out more about the Pash-shan, and she is gifted in many ways that would be of great use to us. I wonder if it would not be wise for us to speak to her of these matters. I feel sure that she would feel as we do and that she could be of great use—” He broke off, noticing that Neric was staring at him in disbelief.

“You would tell that one?” Neric said. “You would put our lives into the hands of that daughter of privilege and birth-honor? You make me doubt my judgment of your wisdom.”

Neric was leaning forward so far in his agitation that he suddenly lost his balance, and for a moment he struggled, flailing his long thin arms, in his effort to keep from pitching forward. When he had regained his equilibrium, he went on. “Your Genaa,” he said, “is a natural Geets-kel. She will surely be asked to join their exclusive society. Remember I spoke of overhearing the discussion concerning the qualifications for new members? They spoke of ambition and superior intelligence and the consciousness of being set apart for a high destiny. In other words, they are looking for pride and arrogance and contempt for those who are less fortunate and less gifted. Your beautiful proud Genaa is exactly what they are seeking, Raamo.”

Raamo stared at Neric in amazement. “I feel that you are judging Genaa unfairly,” he said. “I feel certain that if you came to know her better—”

“And I feel certain,” Neric interrupted shrilly, “that her beauty has swayed your judgment.”

“Perhaps,” Raamo said. “But something that concerns your childhood is swaying yours.” He smiled apologetically. “You were not blocking and I—”

For a moment Neric glared at him, and then, rocking backward, he burst into laughter. “And you pensed me,” he said. “And truly. You must know, then, Raamo, that my childhood does still sway me at times. My parents, both of them, were among the wasted. Not the kind of wasting we know now, which is sometimes swift and final, but the kind that made them into constant Berry-dreamers, unfit for any kind of useful work. We lived in a makeshift nid-place, high up in the twigs of Orchard-grand, and ate and wore only what was provided for us by the charity of the guilds to which my parents had once belonged. They were outcasts—we were outcasts—and I blamed them and whatever it was that had made them what they were. I both loved and despised them. They died during my thirteenth year, and substitute parents were assigned me during my Year of Honor. But as you have truly pensed, I have not forgotten them—or my unfortunate childhood. It seems I am still harboring some of the resentment I had then for those who seemed more fortunate than I.”

Neric laughed again, so freely that Raamo found himself laughing, too. At last, sobering, Raamo said, “I will speak no more of Genaa, at least for now. Perhaps we both need to look more carefully into our judgment of her before we consider this matter further.”

Neric nodded, wiping his eyes. Then, his eyes blinking rapidly and his face twitching with the intensity of his feelings, he was suddenly deadly serious. “Have you heard news of your sister?” he asked. “I would have visited her long ago, had I not been sent so suddenly to Farvald.”

“I have had many messages,” Raamo said. “My mother hires a message bearer almost daily. But she says only that Pomma is much the same. I fear that, knowing I am unable to visit them or do anything to help, she is only trying to spare me mind-pain.”

Neric nodded. “I will go tomorrow,” he said, “and see for myself. And I will do what I can for her.”

“I thank you,” Raamo said.

“Do not thank me,” Neric said. “I will be unable to do anything that is really helpful, except to bring you a true report on her condition. That much I will do early tomorrow morning. But as for now, let us continue with our planning. I was thinking, before we were sidetracked by our discussion of the beautiful Genaa, that we must concentrate our attention on the Pash-shan. I am sure that the key to the secret lies with the Pash-shan and their relationship to the Geets-kel. We must watch and listen for any mention, any unblocked thought, concerning the Pash-shan, and we must also investigate everything that shows evidence of their influence in Green-sky. Do you agree?”

Raamo nodded. “I think,” he said, “that the withering of the Root is truly troubling to D’ol Regle. When he spoke to us of the evil influences of the Pash-shan in Green-sky, I felt—well, he was blocking of course, and I could not truly pense him—but I felt an edge of difference between the inward and outward meaning of his words. Until he began to speak of the Root. Then his troubling was true and deep.”

“Ah,” Neric said. “That is of interest. I wish that we could see the Root for ourselves. I wish you were further along in your novitiate and were soon to accompany the processions. But that will not be for at least a year.”

“Then let us be our own procession. Let

us

go down to the forest floor.” It was not until he was in the midst of speaking, that Raamo realized what he was saying. But even as a tremor of shocked surprise at his own audacity shook him, he was overwhelmed by a rush of other emotions. Fear and dread mingled in wild confusion with a strange feeling of relief, as if a voice, rising from the dark depths of his soul, was saying, “At last! At last!”

W

HEN RAAMO PROPOSED THAT

he and Neric go together to the forest floor, Neric seemed, for a moment, to be stunned by the very thought. But only for a moment. Then excitement flared in his eyes like a sudden sunrise. “Of course,” he said. “Of course. I don’t sec why I hadn’t thought of it before—except that we are so carefully trained to find it unthinkable. And why? Now that 1—we, that is—have thought of it, it seems that there must be more to our dread of the forest floor than just the threat of the Pash-shan. What can be down there that makes it necessary for Kindar not only to stay far above, but even to keep their eyes averted? What can it be that is so evil that we must not even look in its direction?” Leaning forward, Neric pounded his fist on a branch in excitement. “You are right, Raamo. We must go to the forest floor. We will go—on the next free day. And that is only two days from now. We must make our plans very carefully.”

There are times when two days can last an eternity, and others when the hours disappear like minutes. The two days that followed Raamo’s meeting with Neric somehow managed to be both. At times Raamo thought the two days would never end, and at others he was appalled to realize how little time remained. He slept but little during the two nights, and when he did sleep, he dreamed. Each time he sank slowly into restless slumber, he began to dream—and always it was the same dream.

It began in a dark obscurity that gradually lightened into drifting gray clouds. As the clouds became less dense, they were penetrated by dim rays of greenish light, which made visible a strange scene, a scene muted by thickly clustering shadows and yet full of strangely distinct and vivid details.

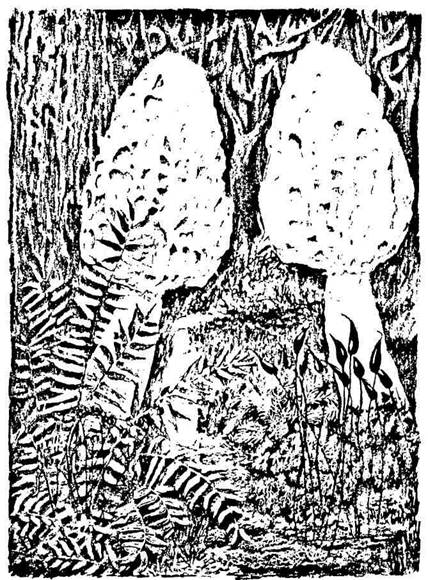

A wall rose up on the left, a rough bark-covered wall that seemed to be the trunk of an enormous grundtree. Near it two huge mushrooms stood like pillars on each side of a pathway that wound away into a green tinged darkness. Standing there, between the mushroom guard posts, Raamo’s dreamself contemplated the winding path with fear. The fear was sharp and real, as was every detail of the scene before him. His frightened glance registered in intricate detail the shade and texture of the earth below his feet, the pale color of the mushroom columns, and the small bush, heavy with purple bloom, that stood just to the right of the pathway.

Then suddenly, out of the greenish shadow ahead, there came a call for help, and Raamo moved forward into darkness and fear; and awoke, trembling and wet with perspiration.

At last the morning of the appointed day dawned, the special ceremony dedicated to Joy in freedom and relaxation was over, and the free afternoon began. As the other novices lazed in their nids or gathered for games and gossip in the common room, Raamo climbed from his balcony to the roof of the novice hall, and from there, by a circuitous route to the meeting place.

When he pushed aside the curtain of Wissenvine, Neric was already there. As Raamo entered, he sprang up, his thin face twitching with excitement.

“Ah, there you are,” he said. “I have planned our route to the outskirts of the Temple-grunds. We will—” he stopped as Raamo pushed past him and seated himself on a branch.

“I would like to rest a moment first,” Raamo said, “and to hear your news of my sister.”

Neric struck his chest in self-reproach. “Forgive me,” he said. “In my excitement, I had forgotten for the moment. I have gone to the nid-place of your parents, as I said I would, and I have spoken with your mother—and I have seen your sister.” He paused for a moment, and then continued. “She is ill, indeed. She is very pale and thin, and your mother told me that she is no longer able to attend her classes at the Garden. Your mother says that she eats very little—except for Wissenberries.”

Raamo shook his head in exasperation. “Why do they permit it?” he said. “I feel sure they do her harm.”

“Your mother, I think, agrees with you. But Pomma complains of great pain when she is without the Berry, and her begging weakens your mother’s resolve to keep them from her.”

Neric’s eyes searched Raamo’s face, and he put his hand on Raamo’s shoulder. “Your sister is still able to leave her nid at times,” he said, “and during the ceremony of healing her responses were clear and strong. I think there may still be some—”

“Hope?” Raamo asked.

“Well, yes,” Neric said. “If one finds comfort in hoping. But I, for one, find more solace in action. I had meant to say that there might still be some

time.

A little time to search for an answer—a cause—perhaps a cure.”

There may be some time—a

tittle

time—only a little time left for one so young. The thought seemed to drain the brilliance from the sunlit leaves and blossoms and poison the rainwashed air with bitterness. If the source of the evils that were plaguing Green-sky and its innocent inhabitants lay, indeed, with the Pash-shan, Raamo felt that he would be willing to do whatever might be necessary to find the solution, even if the search took him into the very tunnels of the monsters.

“Let us go,” he said, and Neric looked at him sharply, surprised at the harshness of his voice.

The pathway lay first along small offshoot branches, through dense growths of leaves and twigs, and finally into the branches of an uninhabited grund that grew on the outskirts of the Temple Grove. Gliding among the branches of the Temple-grunds would have been dangerous, inviting observation by dozens of curious eyes; but here there was little chance of being seen. Raamo and Neric launched themselves into open space and drifted downward.

Unlike the glidepaths in cities and towns, which were carefully cleared and broadened, the route they now followed was narrow and twisting and overgrown with small branches and heavy growths of Vine. Twice they were forced to land and walk until they came to another area open enough for gliding. Soon after the beginning of their third glide, they saw, directly below them, an enormous branch, many feet in diameter and unmistakably a part of the lowest grund-level. Banking sharply, they spiraled down to land on its broad surface. From here to the forest floor, more than a hundred feet below, there were no more branches, but only tree trunks and tangled interwoven growths of Vine. The enormous unbroken surfaces of the grundtrunks were impossible to climb, except when they were strung with ladders as they were between branch levels in the cities. The smooth slender boles of the rooftrees were climbable only by those gifted with strong limbs and a simalike agility at shinnying. So the best route to the forest floor, if one could be found, would be a place where a cluster of Vine stems formed a ladderlike network. A glide to the floor would, of course, be possible but extremely dangerous, since one would land among tall fern, probably far from a means of retreat to the higher levels, and quite possibly very near the mouth of a Pash-shan ventilation tunnel. Walking along the broad branchpath of the forest grund, Raamo and Neric looked carefully for a suitably heavy growth of Vine.