Bette and Joan The Divine Feud (13 page)

Father and daughter embraced in tears. That settled, Mayer was ready to talk terms for a new singing contract for Joan. But first, she had a confession to make to L.B. In a moment of madness the previous evening, while Virginia and Darryl Zanuck were at her house for dinner, she had played her recordings for the Twentieth-Century Fox mogul. Zanuck was thrilled, of course, and made her an offer to join his studio, where Shirley Temple was currently raking in the cash from

her

musicals. "But what did you say?" asked Papa Mayer. "I told him," said Joan, bowing her head, "that my first loyalty was to my family, to you ... [head raised] ... if the terms are favorable."

Crawford was given a fresh five-year contract with Metro, at $250,000 a year, with twelve weeks off every year, exclusive radio rights, and a clause specifying that she could be loaned out "to major studios only."

A costly musical extravaganza was announced as her next picture. Joan would star in the one-million-dollar production of

Ice Follies of

1939, with James Stewart and Lew Ayres as love interests, the entire International Ice Capades as backup, and six new songs composed specifically for her singing debut. On July 31, 1938, while the picture was in production, the Los Angeles

Times

reported that "another edition of the new Joan Crawford series is almost ready. This, the latest of a dizzying number of metamorphoses, will show Miss Crawford as a singer of serious music."

"It's a swell voice," said another reporter, "with a range of two octaves, and a couple of notes at each end to spare. All Joan has to do is decide whether or not she is going to be an operatic mezzo-soprano or a torchy contralto."

"Crawford's singing is going to be as sensational as Garbo talking," a publicist for the picture told Hedda Hopper, who announced that Joan was scheduled to perform at the Metropolitan Opera House in New York that fall, when the new movie was scheduled for release.

Unfortunately, the world and her fans never got to judge Joan's musical talent for themselves. In post-production, four of her six songs were cut from

Ice Capades,

and on the two remaining her voice was dubbed. "It was sabotage," Crawford said. Her singing and years of practice were eliminated because of the threat she posed for the studio's other singing sensation, Jeanette MacDonald.

Ice Capades of

1939 had the same plot and costar (Lew Ayres) as MacDonald's latest musical,

Broadway Serenade.

"They knew all that when we were going in," said Joan. "But then Miss MacDonald heard my singing. She had no idea I was so good. She told Mr. Mayer that there wasn't room for both of us at the same studio. Mayer could not afford to lose Jeanette. Her movies were still very popular. Something had to give. Unfortunately, it was my songs."

"It stinks," Joan told reporters of

Ice Capades of

1939. She wouldn't talk about the picture, she said, but she had other news for them. With a heavy heart, she announced she was divorcing her second husband, Franchst Tone.

The breakup surprised few. The signs had been scattered around Hollywood for two years. His once-promising film career had been reduced to playing second and third leads to his wife in her starring pictures. In

The Gorgeous Hussy

his part came to twenty-six lines. When he balked, L. B. Mayer insisted that they needed "an important actor to walk off into the sunset with Joan Crawford." He did the part but pouted and "wouldn't speak to me for days," Joan complained. In his next Crawford picture,

The Bride Wore Red,

he had a costarring role, but it was that of the village postman.

"Sensitive husbands don't like second billing," said Joan of Tone, who began to drink. "Vodka zombies," said Ed Sullivan. Joan said his drinking affected their sex life (and no doubt, her complexion). Once or twice, she said, he beat her up. She loved the guy, and they always made up,

after

Franchot "knelt before her, made a dutiful recital of his misdeeds and begged for her forgiveness."

"She humiliated the poor bastard," said Bette Davis.

It was Franchot's sexual forays that eventually unnerved Joan. She told Katharine Albert that she had followed him one night and found him in the arms of a cheap starlet. "It wasn't the cheating that bothered me," said Joan. "It was the possibility that the girl could blackmail us."

In June 1938, while she was making

Ice Follies,

Tone moved out of Crawford's Brentwood mansion. Not long after, his contract was terminated by M-G-M. Among the few who rallied to his side was Bette Davis. She called the actor and asked if he cared to work with her in

The Sisters,

due to start filming that month at Warner Bros. Tone passed once more on Bette. He was moving to New York, to work in the theater, he told her. One month later Joan announced their official "trial separation." In September she filed for divorce. In April 1939, a week before the divorce hearing, she flew to New York to meet with Tone. They dined and danced at The Stork Club, and appeared very cozy at the opening of Bette Davis' new film,

Dark Victory,

at Radio City Music Hall. Their divorce was still going through, Joan told Walter Winchell; they would be represented in court by proxy. "This is

our

way of being civilized," the star added.

"Well, it's all disgusting," said Florence Foster Parry of the Pittsburgh

Press.

"It served the purpose of getting the divorce on the front pages again—alongside the collapse of Spain and the push of Hitler."

Then Joan was told that at least one party had to appear in court or the hearing would be canceled. "It is appalling," said Foster Parry in her update, "that Miss Crawford, with the tears of the Last Reunion scarcely dry, must submit to the embarrassment, the inconvenience, the indignity of a personal appearance in court."

On the day of the divorce, accompanied by her agent, Joan appeared, costumed, wearing a tailored coat and a wide-brimmed hat that, she told reporters, necessitated her being up until three in the morning, "steaming the brim just right, so it fell over the top half of her face." She told the judge that Tone had grown "sullen and resentful," and the decree was granted. "No more marriages," she said to the press gathered in the hallway, emphasizing that she was not removing men and their physical charms from her life forever, because "sex is part of what keeps me young."

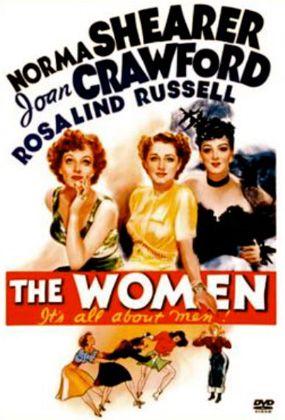

The Women

"I like Bette Davis. I think she's

a real actor, don't you? I never

liked Joan Crawford at all.

Never. I hate fakes. She was an

awful fake. A washerwoman's

daughter. I'm a terrible snob,

you know."

—LOUISE BROOKS TO

JOHN KOBAL

"It is sad that one of Joan

Crawford's biggest

disappointments is that she's not

in the dramatic category with

Bette Davis and Margaret

Sullavan. When people say to

her: 'If you could only do stories

like Bette Davis does,' Joan sees

red."

-A COLUMN ITEM IN 1938

In March 1939 columnist Sheilah Graham reported, ''After three misses in a row, if Joan Crawford doesn't come up with a hit picture soon, she will be joining Luise Rainer in the Hall of Forgotten Stars at Metro." But Joan at this time had already planned her comeback. For her next M-G-M picture she intended to forsake music, culture, and tears. She was ready to infringe on Bette Davis' territory by playing her first authentic bitch—as Crystal Allen in Clare Boothe Luce's

The Women.

Playing a scheming, hard-as-nails husband-stealer would not require enormous research for Joan, Hollywood believed. It was the news that she had agreed to work with

and

take second-billing to her long-time rival actress Norma Shearer that intrigued and delighted all.

In her mellow moments, Joan liked to refer to Norma Shearer as "Miss Lotta Miles." The title referred to Shearer's employment as a model for a rubber tire company during the early days of her career. Norma began in films in 1920 and was already a star in 1925, when Crawford arrived at M-G-M. It was Norma's friendship, and 1927 marriage to L. B. Mayer's first lieutenant, Irving Thalberg, that led to her prominence in pictures, Crawford declared. "She doesn't love him, you know," she told Dorothy Manners. "She got married for the sake of her career, much like a nun who gives herself to Christ, to fill her inner needs."

Throughout the 1930s Crawford complained frequently that because of Norma she was forever locked into the number-two spot when it came to good scripts and money spent. "Big-budget costume meant Norma, low-budget ex-shopgirl meant me." Some of the roles she lost to Shearer were Elizabeth Barrett Browning and Marie Antoinette, both popular and prestigious hits that Crawford envied; although she said she was happy, she missed out on another Shearer role—that of Juliet in

Romeo and Juliet,

with Leslie Howard. "Christ," said Joan to her pal Constance Bennett after the gala premiere of said film, "I couldn't wait for those two old turkeys to die, could you?"

In August 1937, when Irving Thalberg died prematurely at age thirty-seven, it was said that two of the happiest mourners at his funeral were L. B. Mayer and Joan Crawford: Mayer because his control and authority had been usurped by the late producer, and Joan because, with Thalberg gone, his widow would no longer have first dibs on scripts at the studio. But she soon found out Norma carried more clout than ever.

The next year, when Joan was desperately looking for a comeback picture, she heard the studio bought the rights to

Idiot's Delight,

which had featured her old friends the Lunts on Broadway. Clark Gable was slated to play Alfred's part, and Joan knew she was perfect for the Lynn Fontanne role of the pretentious ex-hoofer stranded in a hotel in Europe on the eve of World War II. When she spoke to the producer, Hunt Stromberg, she learned that Shearer had already requested the part. Joan headed straight for Louis B. Mayer's office. "The role calls for an ex-chorus girl," she told the mogul. "That's

me!

Norma can't sing. Norma can't dance. And, furthermore, she's cross-eyed." Mayer explained to Joan what Norma

could

do. In his will, Thalberg had left his wife his large bloc of M-G-M stock. If peeved, she could vote against him. So, to make Norma happy, she would continue to get first crack at all Metro properties. "Christ," said Joan, "she really rode through this studio on his balls, didn't she?"

The lead role in

The Women

also went to Norma. But Mary Haines, noble wife, was not a part that interested Joan. She wanted to play the bitch. "When I read the script," she said, "my eyes and instincts went straight to Crystal. She was the meat and potatoes of the picture. The rest of the girls were cocktail canape." Again L. B. Mayer objected. He told Joan the role was secondary, too small for a star of her stature. "Listen, L. B.," she replied, "the woman who steals Norma Shearer's husband cannot be played by a nobody."

Mayer eventually relented. Crawford could do the picture, but not at her usual star salary. "The son of a bitch made me agree to take a day rate. I worked for

pennies.

But that was okay, I had a hunch this role would payoff."

The director was George Cukor, who said there were 135 speaking roles in total "and all of them women." Rosalind Russell was cast as the gossipy troublemaker Sylvia Fowler, Paulette Goddard as the junior adventuress, and Joan Fontaine as Peggy, the young wife pining away in Reno for the husband she's about to divorce.

The distaff detail encompassed the entire picture, said Cukor. "Everything was female. The books in the library scene were all by female authors. The photographs and art objects were all female. Even the animals—the monkeys, the dogs, the horses—were female. I'm not sure if audiences were aware of that, but there wasn't a single male represented in the entire film, although nine-tenths of the dialogue centered around them."

The problems in wardrobe and makeup could have been enormous, but, said Cukor, "We ran everything like boot camp. There were specific regulations and schedules everyone had to adhere to. Each department was told to be polite and to accommodate everyone within reason, but at the first sign of star temperament, I was to be called."

A hundred coiffures were created, with no two being duplicated. Hairstylist Sydney Guilaroff, who was accustomed to working with either Shearer or Crawford but never both at the same time, solved the dilemma by giving Joan a curly permanent, which left him more time to work with Shearer. "Norma wore her usual 'classic simplicity' do, which took two hours to achieve each morning," said Joan. "I was also supposed to have access to Sydney," said Rosalind Russell, "but he got rid of that by having me wear a hat throughout the picture. At the time I thought it was a divine idea. When I saw the film I realized I was sloughed off."

Adrian designed the clothes, which included 237 different outfits. "Miss Shearer alone had twenty-four changes," said the New York

Herald Tribune.

"In one scene $50,000 worth of real jewelry is worn by three stars. The most expensive is a bracelet and necklace set worth $25,000, worn by Joan Crawford. Not to be outdone Miss Shearer is said to be wearing the most expensive

item—a $20,000

ring. 'If you're any good at mathematics,' said Rosalind Russell, 'that means this costume junk I'm wearing is worth at least five thousand bucks.'"

At the director's orders, none of the players were allowed to see the costumes designed for the other actresses until they arrived on the set ready to work. This enabled Crawford to get the flashiest outfit—a sexy gold-lame gown with a jewel-encrusted midriff. "May I suggest, if you're dressing to please Stephen, not that one," said Norma in character to Joan. "My husband doesn't like circus clothes." "Thanks for the tip," said Joan as Crystal, "but when anything I wear doesn't please Stephen, I take it off."

The largest set, designed by Cedric Gibbons, was the beauty salon used in the opening scene. It ran for thirteen hundred square feet, with twenty-seven separate beauty departments occupied by gabbing females. During the filming of these scenes, the traffic of the stars' entourage, despite the director's plan, became congested. "There were so many personal maids, assistants, and makeup artists on the soundstage," said a production aide, "that the completion of the scene resembled a veritable 'subway run,' as each 'crew' hurried to its own victim, to prepare her for the next take."

The fight scene, with Paulette Goddard and Rosalind Russell kicking and pummeling each other in a bull pen, took three days to film. Goddard complained to

Life

that she had black-and-blue marks over 90 percent of her body, while Russell suffered from a dislocated shoulder.

Joan Crawford too had her trials. She lost eleven pounds in the bubble bath, talking over the telephone. "It took ten hours to shoot," she told

Silver Screen.

"The suds lasted only 15 minutes under the hot lights. Once, the water began to leak out and the crew had to toss me a towel to clothe myself. It could have been

so

embarrassing."

In April 1939, during production of

The Women,

Crawford and Norma Shearer appeared in a duel of glares on the cover of

Look

magazine. "They Don't Like Each Other," the caption read. As the rumors of "soundstage snarlings" escalated, L. B. Mayer, furious that anyone would talk publicly of dissension in

his

family, ordered that the set be closed to all press—except for Thornton Delaney of the New York

Herald.

Delaney, who "went over the head of the doormen, a few AD's, and came away convinced there was nothing to those rumors of gouging, scratching, biting and body checking, which has made this production reportedly the roughest sport in Hollywood." He met with Shearer and Crawford. "See, darling," said Crawford, linking arms with Norma, "we are close friends." Norma, gently extricating herself from Joan, said, "Friends. And professionals."

"It was like a fucking zoo at times," Crawford commented later on. "If you let down your guard for one minute you would have been eaten alive."

AP reporter Bob Thomas said that Joan herself was not above perpetrating acts of petty malice. During the filming of Norma Shearer's close-ups, she refused to meet Norma's eyes while feeding her the lines. And then there was the incident with the knitting needles. Joan had positioned herself in a chair at the side of the camera. She was making an afghan bedcover, which required large needles. As Norma tried to concentrate on her close-ups for the camera, Joan knitted faster. The loud clicking of Joan's needles distracted Norma. She complained. Joan kept knitting, faster and louder, until George Cukor ordered her off the set. "She could be a willful, spoiled child," said Cukor. "Not that Norma was an angel either. Or Rosalind Russell. I had some tedious arguments with Miss Russell. She wanted to give a different performance to what I had in mind for her character."

"George and I had some loud arguments," said Russell. "I saw my character in a different light from him. I wanted to play Sylvia as a brittle sophisticated Park Avenue matron. George wanted me to be loud and exaggerated. Of course he was absolutely right." So right, in fact, that when Russell saw the first week's rushes of her performance she asked for billing

above

the title, with Shearer and Crawford. When her request was denied, she became ill. "I let it be known that I was going to be under the weather for quite a long time," said Russell. Lying in the sun and looking up at the sky when executive Benny Thau called, Roz pleaded ennui. On the fourth day of her strike, when Thau told her that Norma had agreed to her costar billing, the executive asked, "Do you think you'd feel well enough to come to work tomorrow?" Russell replied, "Hmmmm. I'll make a stab at it."

Laszlo Willinger was assigned to photograph the stars for publicity stills. He said both Shearer and Crawford had print approval. "Shearer would look at the prints first and say, 'Gee, this is a beautiful picture of me, but I really don't like the way Joan Crawford looks.' And then Joan would have her turn, and we'd have the same thing. It's a wonder any pictures of them were released at all." One morning Willinger was scheduled to shoot Shearer, Crawford, and Russell for the poster art. "The call was for ten

A.M.

I'm there, ready—nobody. It's ten-thirty, eleven—still nobody. Finally Rosalind Russell turns up and says, 'Sorry I'm late.' I told her, 'You're not late. You're the first one here.'" With a crew of ten on hand waiting, Willinger walked outside and saw Norma Shearer's car drive by. "A little behind her was Joan Crawford, who also slowed down, looked out, and drove on. I thought 'What the hell's going on here?' I called publicity director Howard Strickling and told him, 'There are two stars outside driving around and not coming in.' He said, 'Don't you know what they're doing? Shearer isn't going to come in before Crawford, and Crawford isn't going to come in before Shearer. The only thing I can do is stand in the middle of the street and stop them.' Which he did."