Bette and Joan The Divine Feud (28 page)

"I think Bette quickly grew tired of Sherry," said director Curtis Bernhardt. "I remember a party once—it was some studio shindig. Sherry had been placed at her table, the star's table. She said he had no right to be seated next to her, and she ordered him and his place card to another table. He was ready to kill. When she danced with a man, Sherry broke in, and she refused to dance with him."

"That sounds like something that happened another time," Sherry recalled. "There was a big party that MCA gave for all its top stars at the Beverly Hills Hotel. I wasn't allowed to be at the head table, where all the big shots, including Bette, sat. I was at a side table, with Alan Ladd and his wife. Ladd kept saying, 'Where's your bride?' I said, 'She's over there with the big shots.' Then, when the music started playing for dancing, I went over and said, 'Bette, I'd love to dance with you.' In front of all these people she said, 'I'm

not

dancing with you.' So I just reached down around her waist and lifted her right out of her chair and brought her to the dance floor. She tried to get away from me, but I held her tight and kept dancing with her until the music stopped. Then I let her go. She went running and yelling from the dance floor, through the place, to the ladies' room. I went after her, and Joseph Cotten reached up, grabbed my arm, and said, 'When you catch her, punch her right in the mouth.'"

On October 19, 1949, three months after she left Warner Brothers, and three days after

Beyond the Forest

opened to disastrous reviews, Bette Davis sued for divorce from William Grant Sherry. Charging extreme cruelty and physical abuse, she asked the judge to issue an order to restrain him from doing bodily harm to her and her daughter.

When the suit was filed, Bette gained the sympathy of the public and the press, until two renegade reporters questioned the seriousness of her accusations. Columnist Dorothy Kilgallen said she had met William Grant Sherry a few times, and he didn't seem to be capable of Bette's charges. Reporter Arthur E. Charles also wondered how innocent Poor Bette was in the matter. "Any amateur student of human nature, analyzing the obvious things," said Charles, "must see in Bette Davis' off-screen face the evidences of her long reign as Empress of Burbank. Her mouth, drawn full on the screen, is tight and narrow. Her eyes are wide and cold and queenly. She is as likely as not to raise her hands in a sweep and expect to find a cigarette in her fingers, her wish anticipated. This is okay around a movie set but hardly the thing in a man's own home. If Mr. Sherry had been the brute he was, Miss Davis would certainly have had a number of broken fingers by this time."

There would be no splitting of community property, Bette's lawyer declared, because Sherry had signed an agreement before the wedding ceremony stating that, if and when the marriage ended, he would make no claims on her property. "In other words, Bette Davis could try it out, and if it didn't work, it wouldn't cost her anything," said Arthur E. Charles.

"That's not entirely correct," said Sherry. "I never signed anything until after our daughter was born. Bette asked me to sign a paper saying I wanted nothing from her, that I was in love with her, not her money. I was happy to do that, because I loved and trusted her."

In late October 1949, after the divorce action was filed, and without the former protection of Jack Warner and his publicity guards, Bette learned that she was being portrayed by the press as a shrewd, aggressive, less-than-battered spouse. Refusing to be cast as the heavy in her private life, she decided to change her divorce plans. Sherry wanted a reconciliation ("I loved her and my child; divorce was never my idea"), and she agreed to drop the suit if he would renounce

his

sins, publicly. "I told her I would do anything to preserve our marriage," he confessed to the United Press on October 24, 1949. "I asked her to call off the suit so I can go to a psychiatrist whom I can talk to and who really knows about the mind. My temper is hooked up with the war, I think."

At dinner at Lucy's restaurant with the editors of the mass-circulation magazine

Photoplay,

Bette held Sherry's hand while he repeated his confession. "It was Bette who saved our marriage. She had the intelligence to give me the help I need."

The artist later said, "I was willing to do almost anything so we could stay together as a family. I did have a bad temper, although now I know she caused everyone who had anything to do with her to lose their temper. But I didn't want to lose her or the baby, so I agreed to see this man, a Dr. Hacker, who treated all the big movie stars in Beverly Hills. I took a psychology test with his woman associate, and apparently I upset her. She showed me an ink blot and asked for my response. I told her it reminded me of a kidney operation I had sketched in the hospital. She stared at me and said, 'You mean to tell me that picture doesn't remind you of a woman's vagina?' I said, 'If it did, I'd have nothing more to do with women.'"

Sherry's treatment continued for a few months. "I liked Dr. Hacker. I told him my problems, and he told me his. He had one star client who thought someone was watching her house all the time. He went over to talk to her one night, and the cops arrested him. They thought he was the imaginary prowler. After a while I said to him, 'Listen, doc, when is something going to happen here? When am I going to get rid of my bad temper?' He said, 'Grant, there's nothing wrong with you. You're just a red-blooded American man, married to the wrong woman.'"

In January 1950, still married to Sherry, and five months after she had left Warner Bros., Bette made her first independent film,

Payment on Demand,

at RKO Studios. Her costar was Barry Sullivan, and according to Dorothy Kilgallen and Sheilah Graham, Bette became romantically involved with Sullivan. In late March, on the last day of shooting, when Bette failed to come home, her husband went to the studio and made a shambles of the set when "he found his wife being extravagantly attentive to the actor she was costarring with—and not a camera was turning," said Kilgallen.

"It was the end of the picture, and they always have a party," Sherry explained. "Nobody outside the cast was invited, which was OK with me, but Bette didn't come home. It was late, around midnight, and I thought, 'Something's wrong.' I called the studio and they said, 'No—there's nobody on the set—it's all closed.' So I figured she started drinking and fell asleep in her dressing room. I decided to go and get her. When I got to the studio, I went to her dressing room. There were two parts to it—a living room in the front, and then the dressing area in the rear. Well, the lights were on in the front, and it was dark in the back. So I called out Bette's name. She came out from the back, holding a glass of whiskey in her hand. When she saw me she said, 'Oh ... hi.' And then Barry Sullivan came out behind her. They had been sitting in the dark, and I don't think anything was happening. I wasn't angry either. I said: 'OK, Bette—come on, we're going home.' She said, 'No, I'm not going home.' I picked up her mink coat and put it around her shoulders and repeated, 'Let's go.' She took it off, threw it on the couch, and said, 'No. Leave me alone.' At this point Barry Sullivan stepped in and said, 'Come on, Grant, have a drink.' I said, 'No thanks, Barry. It's late. You better go home too. Your wife will be waiting for you.' I was trying to keep the whole thing calm. But Bette started getting louder, saying she was never going home, and I reached for her. Barry came closer and put his hand on me and said, 'Look here, just take it easy. I don't want any trouble with you.' I told him there was no trouble, to mind his own business, that she was my wife and I wanted to take her home. At that point he put his hand on me again and went to push me. I was in terrific physical shape at that time, and I took a swing at him. I wasn't thinking of hitting him, but I did. His back was to the open door, and when I hit him he went flying out the door and across the street, and he landed in a bunch of tulips."

With that, Bette ran out the door, screaming. The studio police arrived and, pointing to Sherry, she yelled, "Take him! Arrest him!"

"There were three of them," said Sherry. "My temper by then was very hot, and I warned them: 'If any of you guys want to come near me, you're going to get hurt.' One of the policemen was trying to get behind me, and I turned and told him to get back with his friends, that I was taking my wife home. Then Bette started screaming again: 'Call the city police!' 'Oh, sure,' I told her, 'make a big thing out of this, so it'll be in the papers tomorrow.' And she decided not to do that. She eventually agreed to come home with me. Her car and her chauffeur were still there, so she said, 'I'll leave with him.' That was fine with me, but I told the driver I would follow them, and that he better not try to shake me. 'If you dare to turn off, anywhere, before we get to our house, I'll ram my car right into you,' I said. He looked at me, and Bette said, 'He'll do it, he'll do it.' So he drove off. I followed, and we went straight home."

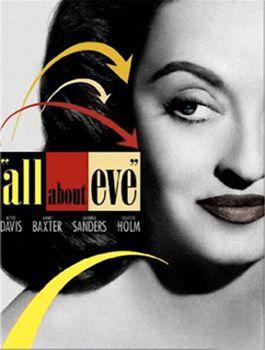

All About Eve

'There goes Eve. Eve evil, little

Miss Evil. But the evil that men

do—how does it go, groom?

Something about the good they

leave behind—l played it once in

Wilkes-Barre."

—BETTE AS MARGO

CHANNING

"Never in the history of motion

pictures has an actress been so

perfectly cast."

—GARY MERRILL

Early in March, when

Payment on Demand

was in its last week of filming, Bette Davis received a call from Darryl Zanuck. He wanted her to read a script about a brittle aging Broadway actress who competes with a conniving young ingenue. The writer was Joseph L. Mankiewicz, who had once romanced and produced "some very bad Joan Crawford pictures." After

All About Eve,

however, he would be referred to by Bette as "a genius, and the man responsible for the greatest role of my career."

''A vicious, absurd little man," was Mankiewicz's description of Darryl Zanuck, who tried to impose his casting ideas on the writer-director of

All About Eve.

Zanuck's first suggestion for Margo Channing was his top star, Susan Hayward, who at thirty-nine was considered too young for the "over-forty" lead character. Zanuck then suggested a package: Marlene Dietrich as Margo, Jeanne Crain as the sweet but evil Eve Harrington, John Garfield as the director Bill Sampson, and Jose Ferrer as the venomous critic Addison De Witt.

Mankiewicz argued that Jeanne Crain lacked "the bitch virtuosity" for Eve; and the script was too literate for Dietrich, who "poses beautifully but cannot really speak." He insisted on testing Anne Baxter for Eve, and Claudette Colbert was signed to play Margo Channing. "Claudette could have played it beautifully ... bitchily, icily, with a great elegance—a piss elegance, if you like," the director believed. When Colbert missed a step in her home and broke a vertebra in her back, he considered Gertrude Lawrence as a replacement. Mankiewicz sent the script to her lawyer, who asked for changes. Miss Lawrence would not drink or smoke in the movie, and in the party scene she should sing a song on the order of "Bill," the Jerome Kern classic. "I said that had already been done in

Showboat,"

said the director, "and, thankfully, a short time later Bette Davis was signed as Margo."

"Margo Channing was not a

bitch. She was an actress who

was getting older and was not

too happy about it. And why

should she be? Anyone who says

that life begins at forty is full of

it. As people get older their

bodies begin to decay. They get

sick. They forget things. What's

good about that?"

—BETTE DAVIS, 1973

With only ten days before production commenced, Davis was fitted for her Edith Head costumes by night. "It was such a rush, we made a mistake on her dress for the cocktail-party scene," said Head. "It was too loose around the neckline, so Bette pulled it down over her shoulders and she wore it as if it was designed like that." On Sunday she made comparative makeup tests with Fox actor Gary Merrill, who thanked her for coming in. "For this part I would come to the studio seven days and nights a week," said Bette.

While the rest of the cast flew on the company plane to San Francisco for three weeks of filming at the Curran Theater, Bette went by train, accompanied by her secretary, her three-year-old daughter, B.D., and the child's governess, Marian Richards. At the station, Bette was not overjoyed when the photographers started snapping pictures of the young governess. "I was wearing sunglasses and my hair was the same color as Bette's," said Marian. "When we left the train they rushed up and began to photograph me. I said, 'No, please, you're making a mistake. That's Miss Davis back there, in the fur coat, carrying the baby.'"

"I admit I may have seen better

days, but I am still not to be had

for the price of a cocktail—like a

salted peanut."

—MARGO CHANNING

Arriving at the Curran Theater for the first day of filming, Bette flew to Joe Mankiewicz in vocal distress. "I was told by three or four people very close to her that the night before she had a screaming fight with her husband," said Mankiewicz. "She was on the lawn in her nightgown—she and this artist-husband of hers. She screamed so loud at him that she broke a couple of blood vessels in her throat. It gave a husky quality to her voice. She said to me, 'Oh, what am I going to do about it?' I said, 'Honey, we're going to keep it.'"

When she had been signed for

Eve,

Mankiewicz said, he had been warned by "countless directors" that Bette would try to destroy him ("She will grind you down to a fine dust and blow you away"), but from the start of production he found her "intelligent, instinctive, vital, sensitive—and, above all, a superbly equipped professional actress."

Outwardly, Bette was just as complimentary about the director, but under the surface lay a few negative doubts. She was the star of the film, though Anne Baxter as Eve Harrington had more lines and scenes. "I was through in three weeks, but poor Anne had to work the entire schedule of ten weeks," said Davis in mock sympathy. She also suspected that Joe Mankiewicz favored Baxter. "When you work on a film with other actresses, and one thinks the director is having an affair with the other one-then there's going to be some sort of conflict," said Davis' secretary, Vik Greenfield. "There was no love lost between Bette and Mankiewicz. Years later we were at Sardi's one night when Bette gave Glenda Jackson an award. Mankiewicz was there also and Bette was so cold to him. I didn't know why, because the man had coaxed such a brilliant performance from her as Margo Channing. Then, a short time after that, we went to see Anne Baxter in

Applause,

and when we were backstage, Bette came right out with it. She asked Baxter if she had an affair with Joe during the making of

All About Eve.

'No,' said Baxter. 'I always thought you did,' said Bette."

The entire cast of

All About Eve

were "first-rate," said Bette, with only one bitch in the bunch—Celeste Holm. A class act, and winner of an Academy Award for

Gentleman's Agreement,

Miss Holm annoyed Bette by giving her "a cheery good morning" each day. "Oh, these

terrible

good manners," Bette snapped eventually. "I never spoke to her again after that," said Holm.

The work process was "like a delightful group-therapy session, with Mankiewicz as the psychiatrist," said Anne Baxter. George Sanders as the acidic Addison De Witt had "a low energy level" and had to be pushed and prodded into his Oscar-winning performance. When George's current wife, Zsa Zsa Gabor, arrived on the set one day and announced, "I must haff George to go shopping," Mankiewicz politely informed her, "We're making a fucking picture, honey." And Marilyn Monroe, in her major debut as Miss Caswell, the decorous but dim-headed starlet, was "just another chorus girl." She had only two lines to deliver in the San Francisco theater lobby. "Tell me this," she asked George Sanders, "do they have auditions for television?" "That's all television is, my dear. Nothing but auditions," Sanders replied. "She got it right, after ten takes," said Gary Merrill. "When she left, we all wondered what was going to happen to that dumb blonde."

In San Francisco, Bette Davis had her own car and chauffeur, who doubled as a bodyguard. "He was a great big black guy, and he'd chauffeur B.D. and me around," said Marian Richards. "He also had a picture of Grant [Sherry] in his pocket, so he'd know if Grant showed up. Bette didn't want him in San Francisco. She already had stars in her eyes, because she was falling for Gary Merrill."

Merrill, the fifth-billed actor in the film, played Margo Channing's love interest, director Bill Sampson. On the first day of shooting, the actor from Maine established his mettle with Davis. Rehearsing onstage at the theater, Bette whipped out a cigarette from her silver case, put it in her mouth, and waited for Merrill to light it. He refused. "And why

not?"

Bette inquired. "Because I don't think Bill Sampson would light Margo's cigarette," said Merrill. After pondering this, Bette nodded her assent. "You're quite right, Mr. Merrill. Of course he wouldn't."

Bette Davis and Gary Merrill, "All About Eve"

The actor soon became a comfort to Bette during filming. "I was miserable, utterly," she said, referring to the recent troubles with her husband. She welcomed the attention and humor of her costar Merrill. "Would Miss Davis like coffee? A cigarette? A sandwich? Someone murdered?"

"He's from New England," Bette marveled, "a beachcomber, and an individualist. He doesn't care what anyone thinks of him. I envy that. I care a great deal what people think of me."

Akin to their characters, Margo and Bill Sampson, Bette and Gary soon discovered they were deeply in love. "I was irresistibly drawn to her," said Merrill. "My first feeling, of compassion for this misunderstood talented woman, was quickly replaced by a robust attraction, an almost uncontrollable lust. I walked around with an erection for three days."

It was evident to all that Bette's spirits had lifted also. "She is having fun again," said Cal York in his column. "She plays records on the set and dances the Charleston for the entertainment of the cast members."

She and Merrill "formed a kind of cabal," Celeste Holm told Kenneth Geist, "like two kids who had learned to spell a dirty word. It was not a very pretty relationship, as they laughed at other people together."

Her marriage to William Grant Sherry was over, and she was filing for divorce, Bette told everyone—except her husband back in Laguna. "Grant sent her a letter on her birthday," said Marian Richards. "In it he said he loved her very much and would do anything to make their marriage work. She read the letter out loud in front of her guests at a party. She thought it was the funniest thing, but no one laughed. Everyone felt it was cruel."

"Infants behave the way

I

do,

you know. They carry on and

misbehave—they'd get drunk

if they knew how—when they

can't have what they want.

When they feel unwanted or

insecure—or unloved."

—MARGO CHANNING

When filming was completed in San Francisco, Bette returned with the troupe to Los Angeles, but not to Grant Sherry. While her husband awaited the return of his wife and child in Laguna, Bette went into hiding in Los Angeles. "We stayed at various houses in Beverly Hills, producers' houses, directors' houses," said Marian Richards. "We were on the run from Grant. Bette used to call us 'the molls.' There was B.D.; Bette's sister, Bobby; the secretary. We went from place to place. Once we stayed at Katharine Hepburn's house, while she was out of town. Bette was terrified that Grant would find her. One night she woke me up at two o'clock in the morning and insisted that we go to the kitchen so she could cook for me. When she got nervous she liked to cook. After a few drinks the actress side of her would appear. 'I wonder if he's going to come after us and kill me?' she would say, playing these big dramatic scenes, which I thought were hilarious. There was also a certain amount of guilt involved in her behavior, because Gary Merrill stayed over some nights. They would come down together for breakfast in the morning."

Merrill was married also, for eight years, to an attractive blue-eyed blonde called Barbara Leeds. Attending a party in Malibu one night, "in an alcohol daze," the actor told the other guests that he'd marry Bette Davis" 'if she'd have me'—not exactly the sort of thing to say in front of one's wife."

Divorce proceedings were instituted by Merrill's wife the next day.

William Grant Sherry wasn't as easy to dislodge. When Bette's lawyers told him she wanted a divorce, they suggested he go to Las Vegas for the separation. He refused. "I knew nothing about Merrill and I didn't want a divorce," he said. To force him to reconsider, Bette immediately sold their Laguna Beach home and his studio. She also closed out their joint checking accounts. "I was left with no money," he said. "I had to move into a smaller house down the street. It was a shack where her sister, Bobby, had lived. If you drove a nail in the wall to hang a picture, it went through to the other side. Weeding outside one day, I found a strange-looking wire and traced it up to the attic. Bette had the place bugged. There were microphones placed in the ceiling over the bedroom. She was doing the same thing her first husband did when he found out she was having an affair with Howard Hughes."