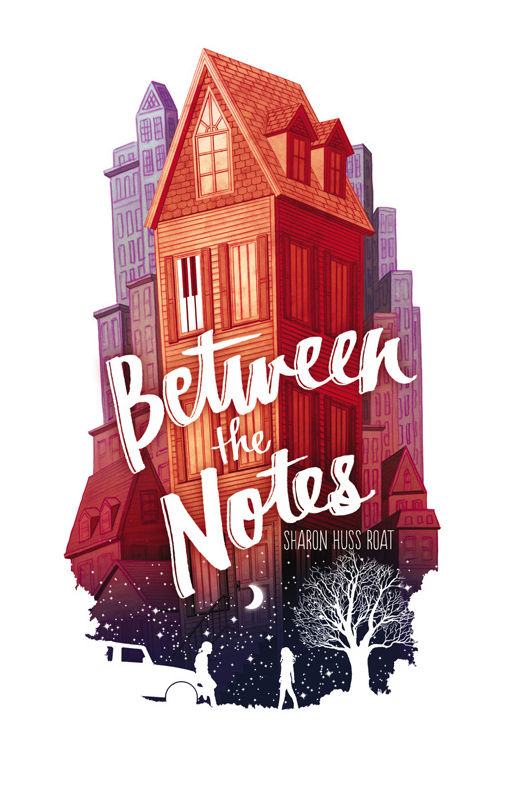

Between the Notes

Authors: Sharon Huss Roat

TO RICH, SEBASTIAN, AND ANNA

I

came home from school on a Thursday in early September to find my parents sitting on the couch in the front room, waiting for me. I knew immediately something wasn’t right. We never sat on that couch. We never even walked into that room, with its white carpet and antique furniture. And what was Dad doing home from work, anyway?

My mother was wringing her hands, literally, like she was squeezing water out of her fingers, too preoccupied to ask me to take my shoes off in the foyer.

“What’s wrong? Where’s Brady?” I naturally put the two together before I realized it couldn’t be him. They would not be sitting here so calmly if something had happened to my brother. There’d be a note on the kitchen counter, a frantic phone message from the hospital.

“He’s at school. He’s fine. Kaya’s fine,” said Mom. “Everything’s fine.”

Dad squeezed my mother’s hand. “Have a seat, sweetie.

There’s something your mother and I need to talk to you about.”

Clearly, everything was not fine.

I dropped my book bag on the carpet with a thud that mimicked the feeling in my stomach, and lowered myself into one of my mother’s favorite wingback chairs.

“What did I do?”

Mom laughed, about an octave higher than usual. “

Nothing!

Nothing.”

Then Dad cleared his throat, and they broke the news like it was a hot potato, tossing it back and forth so neither of them actually had to complete an entire, terrible sentence.

“You know, my business . . .”

“Daddy’s business . . .”

“It hasn’t been good.”

“This economy . . .”

“The whole printing industry, really . . . It’s been . . . a difficult few years,” said Dad, nodding and then shaking his head.

“And with Brady’s therapy bills . . .” said Mom.

My spine went stiff. My parents never blamed anything on Brady’s disability. It was an unspoken rule.

“We got behind on some payments,” Dad was saying.

“And the bank . . .”

“The bank . . .”

They paused, neither one of them wanting to catch the next potato.

“What?” I whispered. “The bank what?”

Then Mom started to cry and Dad looked like the potato had slammed into his stomach. “The bank is foreclosing on our house,” he said. “We have to move.”

I suddenly felt small amid the lush upholstery, like the chair might swallow me whole.

“Huh?”

“We’ve lost the house,” Dad said quietly. “We’re moving.”

I couldn’t seem to process what he was saying, though it seemed plain enough. “This is

our

house,” I said. They couldn’t take

our

house. We couldn’t move. Not away from my best friend, Reesa, who lived next door; and my lilac-colored room with its four-poster bed; and the window seat with its extra-fluffy pillows; and my closet where I could see everything; and . . . and my piano room, and . . .

“We can’t move,” I said.

They shook their heads. They said, “We’re sorry,” and “We hate this, too,” and “There’s nothing we can do,” and “It’s the only way . . . ,” and “We’re sorry. We’re so, so sorry.”

I threw a dozen what-if scenarios at them: “What if Mom gets a job?” “What if I get a job?” “What if we just stop buying stuff we don’t really need?” “Get rid of my phone?” “Sell the silver?”

“Your mother

is

getting a job,” Dad said. We wouldn’t be buying anything but necessities, the silver had already been sold, and yes, they’d be canceling my cell phone service. Even with all that, we still couldn’t afford the mortgage. In fact, we’d barely be

making ends meet in the way-less-expensive apartment we’d be renting.

“What about Nana?” My grandma Emerson lived about two hours away in a farmhouse. She had chickens and made soap from the herbs in her garden. Lavender rosemary. Lemon basil. She always smelled like a cup of lemon zinger tea. “Can’t she loan us money?”

Dad dropped his chin to his chest.

“Ivy,” said Mom, “she lives off Social Security and the little bit she makes selling her soap at craft fairs. She can’t help us.”

“Aunt Betty? Uncle Dean?”

My parents shook their heads. “They have their own problems, their own bills, their own kids to send to college,” Dad said.

The air went out of my lungs; my bones seemed to go out of my limbs. I couldn’t even lift an arm to wipe my tears.

“I know this is hard, but it’s necessary.” She paused. “Please don’t cry. The twins will be home soon. We don’t want to upset Brady.”

I took a shuddery breath, but the tears were refusing to stop. Mom looked nervously out the front window.

“The bus is coming,” she said. “Here.” She offered me a wad of Kleenex.

I nodded, took the tissues from her hand, and sniffled my way to the stairs. We didn’t cry in front of Brady. We didn’t raise our voices or have freak-outs of any kind if we could help it.

My little brother had a seizure disorder when he was a baby. His brain had been wracked by spasms for months, and while they had finally stopped, he now struggled to walk and talk and understand the world around him. If you got angry or emotional in front of him, he thought you were upset with him or, as the doctors said, he “internalized.” Then it took hours to pry his hands away from his ears and calm him down.

I went upstairs to the music room and closed the door. It had taken a special crane to get the baby grand up here through French doors that opened onto the balcony. I sat at the piano bench and played a tumble of scales and chords until my hands turned to heavy bags of sand and I dragged them over the keys. The resulting noise was satisfying. It sounded exactly how I felt.

Out the window, I saw Brady and Kaya walking up our long driveway. They were six years old and I was sixteen. I remembered when my parents brought them home from the hospital. Brady was perfect then. The seizures didn’t start until six months later. We were so worried Kaya would get them, too, but she never did.

She held his backpack for him. It always took a while for them to make their way to the porch, because Brady stopped every few steps to pick up a pebble or stray bit of asphalt and throw it into the grass. We had the cleanest driveway on the planet.

When they neared the house, Mom and Dad walked out to greet them with hugs and pasted-on smiles. I wasn’t ready to

pretend everything was okay, not even for Brady.

I just continued to play my piano.

When I saw where we were moving a week later, my throat closed up and I could barely breathe. Mom made it all sound like a fabulous adventure, like camping in a deluxe cabin.

“It’s really very nice,” she said. “Three bedrooms, two baths, walk-in closets. Even wifi.”

“Golly, Mom. Do you think we’ll have running water? And heat?” Sarcasm was one of the few ways I could say what I truly felt in front of Brady, as long as I paired it with a smile.

“Of course, sweetheart.” Mom smiled sarcastically right back. “Refrigeration, too. And bunk beds!”

“Brady get bunk bed!” he exclaimed with a sweet smile.

It was amazing how easily six-year-olds could be won over by the promise of narrow sleeping surfaces stacked on top of each other. Mom and Dad were just relieved he wasn’t traumatized by the whole thing, and made no attempt to redirect him to a new topic or coach him to speak in complete sentences like they usually did.

I ruffled his soft, blond hair, the hair I wished I could trade for my mop of brown, frizz-prone curls. “Bunk beds are cool.” We’d been talking up the benefits of the bottom bunk in particular, so he wouldn’t want the top. It was too dangerous for him.

He hugged my leg. “Ivy bunk bed!”

I kissed his head and quickly turned back to the dishes I was wrapping in newspaper. My bags and boxes were packed with what little I was allowed to take to our new home. Essentials and favorites only, Dad had said. The rest would go into storage or be sold, because the new place was “more economical.” I was pretty sure that was code for “crappy little apartment,” but I wouldn’t know for sure until Dad got home and took us to check out the place.

The phone rang and I heard Mom answer in the next room, a den with a circular fireplace we always sat around on New Year’s Eve to roast marshmallows.

“Oh, hi, Reesa. . . . Yes, she’s here. Why don’t you come over? Ivy’s just—”

I lunged for the kitchen phone. “Mom! I’ve got it. You can hang up.”

I waited for the click. “Hey. I’m here.”

“I kind of noticed that when you screamed in my ear. You want me to come over?”

“No!” I closed my eyes and took a calming breath. “No, I’m . . . Mom has us all doing chores. She’s, um . . . she’s giving a bunch of old dishes away. For a charity thing.”

I wasn’t quite ready to tell her that

we

were the charity thing. I kept thinking if I didn’t tell anyone, it wouldn’t happen.

“Then you totally need me. I know how to pack china so it won’t break,” said Reesa. “Remember my job at the antiques store?”

“You worked there for one day. They made you dust.”

Reesa laughed. “Okay, fine. But I did learn how to wrap flatware before I quit.”

“That’s okay,” I said. “I’m almost done, and we have to go out when my dad gets home, anyway.”

I managed to rush her off the phone before she could ask where we were going. When I hung up, Mom joined me across the table. She slid a dish onto newspaper and folded four corners to its center. “You haven’t told her?”

I shook my head. “Not yet.”

She wrapped another plate, and another, alternately stacking hers with mine. When I placed the last plate on the pile, she rested her hands on top and sighed. “We’re moving this weekend, sweetie. You should tell your friends.”

“I will. I’m just waiting . . .” I didn’t know what I was waiting for. That sweepstakes guy to show up with a gigantic check for a million dollars and a bouquet of roses, maybe? “I want to see it first. That’s all.”

As if on cue, Dad walked into the kitchen and laid his briefcase heavily on the counter. He didn’t say a word. He didn’t have to. His look of nervous resignation was enough to announce it was time to go see our new place, ready or not.

We loaded into the Mercedes SUV, which now sported a handmade

FOR SALE

sign in the rear window. Mom chattered on

about how nice the new apartment was. Her voice sounded thinner than normal, like she couldn’t get enough air. “It’s smaller, of course. But plenty of room for the five of us. Three bedrooms . . .”

She kept saying “three bedrooms” like it was a huge deal. I should’ve known the sleeping accommodations were the least of my troubles. It was like worrying that your tray table is too small on an airplane that’s about to crash.

I hid my face behind the

FOR SALE

sign, picking at the tape that held it in place, while Brady and Kaya bounced in their booster seats. My father steered the car down our long, curving driveway. The wrought-iron gate swung open as we approached, triggered by a motion sensor that was perfectly timed to release us without a moment’s delay. My parents hadn’t installed the gate or the fence around our property to keep people out, but rather to keep Brady in. He had a tendency to wander. Still, it kept visitors from stopping by unannounced, so none of my friends had discovered we were moving yet. I was hoping to keep it that way.

My nail polish, a glossy fuchsia, had started to chip. I scraped one thumbnail against the other as we passed Reesa’s house. Their gate was sculpted of copper with an ornate letter

M

for Morgan in the middle. It was flashy and curvy and shiny like she was. But more important, it was right next door. The distance between her kitchen door and ours was precisely seventy-seven steps—or fifty-three cartwheels. Though we hadn’t traveled via

cartwheel in a few years, we had sworn to always live next to each other, even when we went off to college. Even when we got married. “Our kids will be best friends,” we always said.

I lifted my head like a prairie dog. “Maybe the people who buy our place will rent it back to us.”

Daddy darted a warning glance at me in the rearview mirror. Brady and Kaya didn’t know the house was going to be sold. “Nobody’s buying our place,” he said.

My parents wanted to spare the twins the full details of our situation, so they wouldn’t be overly traumatized. (Was there such a thing as moderate trauma?) We were telling them this was a temporary move while work was being done on the house.

A big fat lie,

I’d said.

A little white lie,

Mom insisted.

“Oh, yeah.” I winked at Kaya, who squinted back. She was totally onto them, but also very well trained in the ways of the let’s-not-upset-Brady bunch.

I twisted around to watch the rolling hills of Westside Falls disappear behind me as we headed toward the city of Belleview, then slouched back down in my seat. Maybe the new place wouldn’t be so bad, after all. Small, but cozy. Like Brady’s bunk bed. Maybe it would be located on one of those cute streets in the city where the houses were like Manhattan brownstones, and I’d be close enough to walk to my favorite shops.

We hadn’t been driving long, maybe six or seven minutes, when my father turned left at an intersection we usually went

straight through. I sat up taller, the fine hairs on my arms standing at attention as we passed some industrial buildings and warehouses, an abandoned gas station, and a vacant parking lot with weeds sprouting through crumbled asphalt. “Wait, we’re not . . . where is this place, exactly?”

“It’s in district.” There was definitely something weird about my mother’s voice. “You won’t have to change schools or anything.”

I froze, swallowing hard. “But it’s . . . it’s not . . .” Another warning glance from my father confirmed what my arm hairs had been trying to tell me.

We were moving to Lakeside.

Like Westside Falls, Lakeside was a suburb of Belleview. But that’s where the similarities ended. Lakeside was a bad neighborhood that had been added to our otherwise posh school district a few years ago when they redrew the boundaries. There wasn’t even a lake there, only a reservoir where they’d flooded a valley years ago to provide water to the nearby city of Belleview. I’d never actually been to Lakeside myself—we never drove this way when we went downtown to shop or go to restaurants—but I’d heard plenty. Somebody’s cousin’s best friend’s mom got carjacked when she took a wrong turn and asked for directions. And everyone said if you wanted to buy drugs, all you had to do was look for a corner where a pair of high-top sneakers were dangling from the phone wires above.