Big Porn Inc: Exposing the Harms of the Global Pornography Industry (40 page)

Read Big Porn Inc: Exposing the Harms of the Global Pornography Industry Online

Authors: Melinda Tankard Reist,Abigail Bray

Tags: #General, #Social Science, #Sociology, #Media Studies, #Pornography

It is lonely sex. With no actual partner, “… there is no before and after, sex occurs in isolation … There is no communication … no emotional resonance to sex …” (Walter, 2010, p. 109). While a man may wish for a satisfying sexual relationship in real life, once he starts using pornography, it often happens that sex with his partner never quite measures up to his fantasies. Dolf Zillman, a leading researcher in the field, found that long-term use of pornography “… breeds discontent with the physical appearance and the sexual performance of intimate partners” (Zillman, 1989, pp. 127–58).

Harm to Relationships:

The lack of respect for women which is the basis of pornography makes equality in relationships impossible. Many men fool themselves into believing that the pornography they consume will stay in the realm of fantasy, thereby keeping it separate from their real-life relationships with women, but “… the more men watch porn, the more the stories become part of their social construction of reality” (Dines, 2010, p. 67). Whether in intimate relationships, in social situations or in the workplace, women will always be seen by men who use pornography as less than equal. The subordinate status given to women in pornographic depictions carries over into every other part of life.

Conclusion

If equality between women and men is ever to be a reality, then pornography has to go. Any activity which encourages men to enjoy, and be sexually turned on by, images of women being hurt and demeaned and humiliated, any activity which subordinates women to men in such an obvious way, will never result in equality and fairness. In free speech terms, pornography robs all women of their free speech rights. In feminist terms, it is not simply a matter of personal choice. It is a highly political activity. The power dynamics involved and the harms done to women show pornography to be an activity privileging men’s desires over women’s rights.

Recent examples, cited earlier, of the United States government and free speech advocates suspending their absolute dependence on freedom of speech in the interests of fairness show that it can be done. Pornography does harm to half the world’s population in the name of free speech. The question must be asked: Is free speech really free if it is not free and fair for all?

Bibliography

Campbell, Tom (1994) ‘Rationales for Freedom of Communication’ in Tom Campbell and Wojciech Sadurski (Eds)

Freedom of Communication

. Dartmouth Publishing, Aldershot, pp. 17–44.

Dines, Gail (2010)

Pornland: How Porn Has Hijacked Our Sexuality

. Beacon Press, Boston; Spinifex Press, North Melbourne.

MacKinnon, Catharine A. (1987)

Feminism Unmodified: Discourses on Life and Law

. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA.

MacKinnon, Catharine A. (1994)

Only Words

. HarperCollins, London.

McLellan, Betty (2010)

Unspeakable: A feminist ethic of speech

. OtherWise Publications, Townsville.

Tankard Reist, Melinda (12 November, 2010) ‘Why is Amazon promoting sexual abuse of children?’

The Drum Unleashed

, <

http://www.abc.net.au/unleashed/41030.html

>.

Walter, Natasha (2010)

Living Dolls: The Return of Sexism

. Virago, London.

Whisnant, Rebecca (2004) ‘Confronting Pornography: Some Conceptual Basics’ in Christine Stark and Rebecca Whisnant (Eds)

Not For Sale: Feminists Resisting Prostitution and Pornography

. Spinifex Press, North Melbourne, pp. 15–27.

Zillman, Dolf (1989) ‘Effects of Prolonged Consumption of Pornography’ in Dolf Zillman and Jennings Bryant (Eds)

Pornography: Research Advances and Policy Considerations

. Erlbaum, Hillsdale, NJ.

___________________________

1

For a list of the various arguments, see Campbell (1994) p. 17.

2

Defining pornography as “graphic sexually explicit materials that subordinate women through pictures and words” Catharine A. MacKinnon and Andrea Dworkin attempted to highlight the fact that pornography harms women by what it says and what it does (see MacKinnon, 1994, pp. 15–16).

3

The fact that Julian Assange has been charged with sexual molestation under Swedish law is a separate matter altogether. While his supporters have sought to confuse the 2 issues, saying that the allegations of rape are simply a mechanism for having him extradited to Sweden and then on to the United States, the charge of sexual misconduct is real and ought to be dealt with independently from the WikiLeaks issues.

4

Subsequently, on 20 March, 2011, Pastor Jones did carry out his threat to burn the Koran in the name of freedom of speech and, as a direct consequence of his action, 7 members of the United Nations staff in Afghanistan were murdered on 2 April by protesters incensed at the desecration of Islam’s holy book. Pastor Jones remarked that he had no regrets about his action.

Harm to Relationships:

The lack of respect for women which is the basis of pornography makes equality in relationships impossible. Many men fool themselves into believing that the pornography they consume will stay in the realm of fantasy, thereby keeping it separate from their real-life relationships with women, but “… the more men watch porn, the more the stories become part of their social construction of reality” (Dines, 2010, p. 67). Whether in intimate relationships, in social situations or in the workplace, women will always be seen by men who use pornography as less than equal. The subordinate status given to women in pornographic depictions carries over into every other part of life.

Conclusion

If equality between women and men is ever to be a reality, then pornography has to go. Any activity which encourages men to enjoy, and be sexually turned on by, images of women being hurt and demeaned and humiliated, any activity which subordinates women to men in such an obvious way, will never result in equality and fairness. In free speech terms, pornography robs all women of their free speech rights. In feminist terms, it is not simply a matter of personal choice. It is a highly political activity. The power dynamics involved and the harms done to women show pornography to be an activity privileging men’s desires over women’s rights.

Recent examples, cited earlier, of the United States government and free speech advocates suspending their absolute dependence on freedom of speech in the interests of fairness show that it can be done. Pornography does harm to half the world’s population in the name of free speech. The question must be asked: Is free speech really free if it is not free and fair for all?

Bibliography

Campbell, Tom (1994) ‘Rationales for Freedom of Communication’ in Tom Campbell and Wojciech Sadurski (Eds)

Freedom of Communication

. Dartmouth Publishing, Aldershot, pp. 17–44.

Dines, Gail (2010)

Pornland: How Porn Has Hijacked Our Sexuality

. Beacon Press, Boston; Spinifex Press, North Melbourne.

MacKinnon, Catharine A. (1987)

Feminism Unmodified: Discourses on Life and Law

. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA.

MacKinnon, Catharine A. (1994)

Only Words

. HarperCollins, London.

McLellan, Betty (2010)

Unspeakable: A feminist ethic of speech

. OtherWise Publications, Townsville.

Tankard Reist, Melinda (12 November, 2010) ‘Why is Amazon promoting sexual abuse of children?’

The Drum Unleashed

, <

http://www.abc.net.au/unleashed/41030.html

>.

Walter, Natasha (2010)

Living Dolls: The Return of Sexism

. Virago, London.

Whisnant, Rebecca (2004) ‘Confronting Pornography: Some Conceptual Basics’ in Christine Stark and Rebecca Whisnant (Eds)

Not For Sale: Feminists Resisting Prostitution and Pornography

. Spinifex Press, North Melbourne, pp. 15–27.

Zillman, Dolf (1989) ‘Effects of Prolonged Consumption of Pornography’ in Dolf Zillman and Jennings Bryant (Eds)

Pornography: Research Advances and Policy Considerations

. Erlbaum, Hillsdale, NJ.

___________________________

1

For a list of the various arguments, see Campbell (1994) p. 17.

2

Defining pornography as “graphic sexually explicit materials that subordinate women through pictures and words” Catharine A. MacKinnon and Andrea Dworkin attempted to highlight the fact that pornography harms women by what it says and what it does (see MacKinnon, 1994, pp. 15–16).

3

The fact that Julian Assange has been charged with sexual molestation under Swedish law is a separate matter altogether. While his supporters have sought to confuse the 2 issues, saying that the allegations of rape are simply a mechanism for having him extradited to Sweden and then on to the United States, the charge of sexual misconduct is real and ought to be dealt with independently from the WikiLeaks issues.

4

Subsequently, on 20 March, 2011, Pastor Jones did carry out his threat to burn the Koran in the name of freedom of speech and, as a direct consequence of his action, 7 members of the United Nations staff in Afghanistan were murdered on 2 April by protesters incensed at the desecration of Islam’s holy book. Pastor Jones remarked that he had no regrets about his action.

PART FIVE

Resisting Big Porn Inc

Resisting Big Porn Inc

Julia Long

Resisting Pornography, Building a Movement: Feminist Anti-porn Activism in the UK

1

Anti-porn campaigns

A striking feature of this flourishing activism is the centrality of pornography and the sex industry as mobilising issues. Whilst the re-emergent movement is far from homogenous, anti-porn feminism is nonetheless a significant and high-profile element within the new activism. In particular, the

mainstreaming

of pornography and the sex industry has galvanised many new activists to engage in various forms of resistance, including: Web-based discussions, petitioning and blogging; challenging sexist attitudes expressed by friends, family and colleagues; requesting local newsagents to not stock ‘lads’ mags’, or to place them on the

top shelf; writing to Members of Parliament or complaining to the Advertising Standards Association; stickering lads’ mags or sexist posters and advertisements, or disrupting displays of lads’ mags in shops.

Some activism has developed into more formal campaigns. Such campaigns have targeted high street stores, encouraging them not to stock Playboy-branded goods or lads’ mags (or at least not to display such publications at eye-level); in at least 2 cities, Sheffield and Bristol, campaigns have been run against the opening of branches of the American ‘Hooters’ franchise.

2

Most activism to date has concentrated on pornification and sex object culture rather than campaigning around hardcore and Internet pornography, although some groups have used the anti-porn slideshows developed in the US by ‘Stop Porn Culture’

3

as part of training and in awareness-raising exercises.

Three of the most successful and high-profile UK campaigns are

Bin the Bunny, Stripping the Illusion

, and

Feminist Fridays. Bin the Bunny

(see

Fig.1

) was a campaign organised by Anti-Porn London, a group emerging out of the London Feminist Network, which took the form of a series of protests outside the newly-opened Playboy concept store in London’s Oxford Street. The campaign focused on raising awareness about the nature and business of the Playboy corporation,

through producing a DVD, giving out leaflets, talking to passers-by and wearing campaign t-shirts and badges.

Fig. 1

Fig. 1

Bin the Bunny

protest

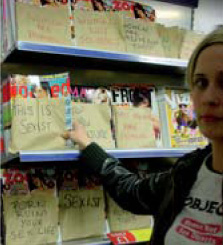

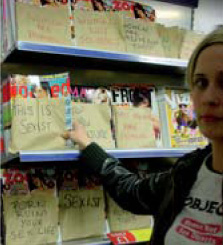

Fig. 2

Fig. 2

Feminist Friday

protest

Stripping the Illusion

and

Feminist Fridays

(see

Fig. 2

) are campaigns run by OBJECT,

4

an organisation which campaigns against ‘sex-object culture’. The former is a highly strategic campaign which challenged the proliferation of lap dancing clubs through successfully lobbying for changes in licensing arrangements. The latter involves direct action protests calling for lads’ mags to be recognised as part of the porn industry, and, if sold, to be covered up, placed on the top shelf and age-restricted.

Feminist Fridays

, held monthly on Friday evenings, take the form of direct intervention in public space, transforming displays of lads’ mags through placing the publications into brown paper bags upon which feminist slogans have been written, sometimes followed by exuberant chanting, singing and dancing.

5

The format of these protests is therefore highly effective at bringing a feminist message into the public realm, and providing an alternative message to that intended by the publishers.

Activist motivation and involvement

Activists I spoke to were highly motivated to challenge porn culture, seeing pornography as part of the backlash against gains made by feminism, and a means by which women are objectified and dehumanised, and violence against women is normalised. Activists spoke of emotions such as anger and distress as a motivation for getting involved in activism. The distress experienced came about for a number of reasons, including male partners’ use of porn, workplace sexual harassment relating to porn, and the undermining effects of the presence of porn within mainstream culture:

Protective measures and support strategies

Protests and actions

Group co-ordinators and members developed a range of practical strategies to ensure that activists felt supported and able to cope with the challenges of a public demonstration. These included:

• Ensuring thorough planning and preparation prior to the action

• Meeting up beforehand to make sure new people were welcomed

• Using resources such as ‘comeback sheets’ to build confidence in dealing with members of the public

• Building group spirit through chant practice, banner-making sessions and sharing practical tasks

• Working as a team and ‘looking out’ for each other

• Providing training for dealing with the media

• Dividing up tasks and agreeing roles (e.g. one person to deal with media interest whilst on a demo)

• De-brief sessions after the actions

• Building informal support networks, including through phone, email and online discussion

• Socialising and celebrating

Knowledge is power

A key part of being involved in activism was the opportunity for activists to build knowledge and become more informed about the issues. Activists spoke of how this opportunity helped them to develop confidence in dealing with hostile or uninformed attitudes from work colleagues, family and acquaintances. The importance of being part of a supportive group was emphasised, as this provided a context for developing networks and gaining knowledge.

Dealing with pornographic material

Trainers responsible for delivering anti-porn awareness raising sessions developed practical strategies for dealing with pornographic content and its potentially distressing and ‘triggering’ effects. These strategies included delivering the training in pairs, providing details of support agencies dealing with sexual violence and offering participants the chance to opt out at any point. While most of the women I interviewed were not generally involved in this kind of work, all groups tended to recognise the need for women to share and discuss feelings and experiences regarding porn in a safe space. In one group, this was built into meeting structures, with time set aside for confidential discussion and sharing, separate from the ‘business’ parts of the meeting.

Managing emotions and group dynamics

Various practical supports, often informal, were developed for managing emotions and group dynamics. For example, Lydia spoke of ‘having to have de-brief sessions’ after group actions:

Combating isolation

For most of the women I spoke to, isolation was a problem that they had encountered prior to getting involved in activism, rather than an issue once they had become active. However, for some anti-porn activists isolation can be a significant and ongoing problem. For women in small communities or rural settings, feelings of isolation and the stigmatisation of the ‘anti-porn’ label can be acute. Measures taken to combat this included online communication with other feminists, and reading online blogs and feminist books. Sharing the company of other women at feminist events such as ‘Reclaim the Night’ marches and conferences was especially valued, particularly if this was a rare opportunity.

Resisting Pornography, Building a Movement: Feminist Anti-porn Activism in the UK

1

It is an exciting and important time to be a feminist activist. As inequality remains massive, misogyny and violence against women remains rife and the backlash against the struggle for equality intensifies – with women being objectified and sexualised by the mainstreaming of the sex and porn industries – women and men across the country are increasingly standing up to object

.

(Publicity for ‘Activism Training’ workshop, Feminism in London Conference, 2009)

The first decade of the 21st century has seen a remarkable resurgence of grassroots feminist activism in the UK. Lively online feminist blogs and discussion groups have appeared. Feminist networks have proliferated across the country, the first and largest of which, the London Feminist Network, has grown from just a handful of members in 2004 to a membership of around 1,600 by December, 2010. The decade saw the revival of ‘Reclaim the Night’ and the instigation of ‘Million Women Rise’ marches against male violence, several large-scale feminist activist conferences, numerous actions and campaigns, and the emergence of a national information and resource organisation – UK Feminista – which aims to help co-ordinate and support UK grassroots feminist activism..

(Publicity for ‘Activism Training’ workshop, Feminism in London Conference, 2009)

Anti-porn campaigns

A striking feature of this flourishing activism is the centrality of pornography and the sex industry as mobilising issues. Whilst the re-emergent movement is far from homogenous, anti-porn feminism is nonetheless a significant and high-profile element within the new activism. In particular, the

mainstreaming

of pornography and the sex industry has galvanised many new activists to engage in various forms of resistance, including: Web-based discussions, petitioning and blogging; challenging sexist attitudes expressed by friends, family and colleagues; requesting local newsagents to not stock ‘lads’ mags’, or to place them on the

top shelf; writing to Members of Parliament or complaining to the Advertising Standards Association; stickering lads’ mags or sexist posters and advertisements, or disrupting displays of lads’ mags in shops.

Some activism has developed into more formal campaigns. Such campaigns have targeted high street stores, encouraging them not to stock Playboy-branded goods or lads’ mags (or at least not to display such publications at eye-level); in at least 2 cities, Sheffield and Bristol, campaigns have been run against the opening of branches of the American ‘Hooters’ franchise.

2

Most activism to date has concentrated on pornification and sex object culture rather than campaigning around hardcore and Internet pornography, although some groups have used the anti-porn slideshows developed in the US by ‘Stop Porn Culture’

3

as part of training and in awareness-raising exercises.

Three of the most successful and high-profile UK campaigns are

Bin the Bunny, Stripping the Illusion

, and

Feminist Fridays. Bin the Bunny

(see

Fig.1

) was a campaign organised by Anti-Porn London, a group emerging out of the London Feminist Network, which took the form of a series of protests outside the newly-opened Playboy concept store in London’s Oxford Street. The campaign focused on raising awareness about the nature and business of the Playboy corporation,

through producing a DVD, giving out leaflets, talking to passers-by and wearing campaign t-shirts and badges.

Fig. 1

Fig. 1Bin the Bunny

protest

Fig. 2

Fig. 2Feminist Friday

protest

Stripping the Illusion

and

Feminist Fridays

(see

Fig. 2

) are campaigns run by OBJECT,

4

an organisation which campaigns against ‘sex-object culture’. The former is a highly strategic campaign which challenged the proliferation of lap dancing clubs through successfully lobbying for changes in licensing arrangements. The latter involves direct action protests calling for lads’ mags to be recognised as part of the porn industry, and, if sold, to be covered up, placed on the top shelf and age-restricted.

Feminist Fridays

, held monthly on Friday evenings, take the form of direct intervention in public space, transforming displays of lads’ mags through placing the publications into brown paper bags upon which feminist slogans have been written, sometimes followed by exuberant chanting, singing and dancing.

5

The format of these protests is therefore highly effective at bringing a feminist message into the public realm, and providing an alternative message to that intended by the publishers.

Activist motivation and involvement

Activists I spoke to were highly motivated to challenge porn culture, seeing pornography as part of the backlash against gains made by feminism, and a means by which women are objectified and dehumanised, and violence against women is normalised. Activists spoke of emotions such as anger and distress as a motivation for getting involved in activism. The distress experienced came about for a number of reasons, including male partners’ use of porn, workplace sexual harassment relating to porn, and the undermining effects of the presence of porn within mainstream culture:

I was surrounded by a lot of misogynist men, and other people in my life had similar attitudes, and … I just felt so unhappy and I felt, I can’t handle [porn] being everywhere, I don’t want to be in a world that’s like this (Sheryl, 30).

Prior to getting involved with activism, women often felt isolated and alone in their objections to pornography. They found friends, colleagues and acquaintances hostile or unsympathetic to anti-porn sentiments, and spoke of their opinions being consistently trivialised or ridiculed. Such hostile responses tended to have a powerful silencing effect, and the need to break this silence and isolation was a strong motivating factor:I remember the first time I clicked on the link for the OBJECT website and I was just so pleased that there were like-minded people out there! (Nadia, 32).

Once involved, the activism was overwhelmingly experienced as affirming and empowering, and the sense of participating in struggle and making a difference was a key factor in maintaining activist involvement:[t]he protest outside the lap dancing club was fantastic … Cos for me, before I found OBJECT I just felt really, um, impotent … So it just feels really good to feel you’ve done something … I do get a lot out of it (Nadia, 32).

However, taking a public stand against porn is far from easy, and challenges inevitably arise. Anti-porn work carries a number of specific stress factors and emotional challenges, including the stress of taking an oppositional stance in the context of a ‘pornified’ society; dealing with pornographic material; public perceptions and negative stereotypes of anti-porn feminists, and the reactions of friends, families and partners. The activists I interviewed were involved in a variety of anti-porn activities ranging from campaigns, petitioning, lobbying, protests and actions to delivering workshops and training, and working within professional settings. Sometimes the work was carried out in the context of paid employment; more often it was undertaken on a purely voluntary basis. The different contexts and kinds of work tended to have different implications in terms of the nature of the stress involved and kinds of support needed, though some challenges were common to all forms of activism. In the final section, I will set out some of the challenges that can arise and outline strategies that activists have developed in order to deal with these.Protective measures and support strategies

[T]he support! I tell you what … the support of feminists, the feminist friends that I’ve made, I feel so much more supported by them mentally and when we’re out in a group doing an action, I know they’ve all got my back (Rita, 53).

The importance of support structures was evident in how groups dealt with the challenges of doing anti-porn work. This support took different forms depending on the nature of the activism, as outlined below.Protests and actions

Group co-ordinators and members developed a range of practical strategies to ensure that activists felt supported and able to cope with the challenges of a public demonstration. These included:

• Ensuring thorough planning and preparation prior to the action

• Meeting up beforehand to make sure new people were welcomed

• Using resources such as ‘comeback sheets’ to build confidence in dealing with members of the public

• Building group spirit through chant practice, banner-making sessions and sharing practical tasks

• Working as a team and ‘looking out’ for each other

• Providing training for dealing with the media

• Dividing up tasks and agreeing roles (e.g. one person to deal with media interest whilst on a demo)

• De-brief sessions after the actions

• Building informal support networks, including through phone, email and online discussion

• Socialising and celebrating

Knowledge is power

A key part of being involved in activism was the opportunity for activists to build knowledge and become more informed about the issues. Activists spoke of how this opportunity helped them to develop confidence in dealing with hostile or uninformed attitudes from work colleagues, family and acquaintances. The importance of being part of a supportive group was emphasised, as this provided a context for developing networks and gaining knowledge.

Dealing with pornographic material

Trainers responsible for delivering anti-porn awareness raising sessions developed practical strategies for dealing with pornographic content and its potentially distressing and ‘triggering’ effects. These strategies included delivering the training in pairs, providing details of support agencies dealing with sexual violence and offering participants the chance to opt out at any point. While most of the women I interviewed were not generally involved in this kind of work, all groups tended to recognise the need for women to share and discuss feelings and experiences regarding porn in a safe space. In one group, this was built into meeting structures, with time set aside for confidential discussion and sharing, separate from the ‘business’ parts of the meeting.

Managing emotions and group dynamics

Various practical supports, often informal, were developed for managing emotions and group dynamics. For example, Lydia spoke of ‘having to have de-brief sessions’ after group actions:

I always made sure I sent round emails afterwards that were positive and upbeat. Often, even when an action had gone well, there would always be a confrontation, obviously usually with a man, or there would be an incredible adrenalin crash because you really had to build yourself up to these things (Lydia, 34).

In other groups, there was a desire to create a structure where emotions could be explored and women could support each other. However, time pressures and limited resources meant that these kinds of structures did not always get beyond the ideas stage. In the meantime, activists developed personal friendships and informal support networks within groups. It was evident that great attention was given to recognising and valuing the contribution of individual activists, perhaps in recognition that their activist work was not always valued by friends and family outside the group.Combating isolation

For most of the women I spoke to, isolation was a problem that they had encountered prior to getting involved in activism, rather than an issue once they had become active. However, for some anti-porn activists isolation can be a significant and ongoing problem. For women in small communities or rural settings, feelings of isolation and the stigmatisation of the ‘anti-porn’ label can be acute. Measures taken to combat this included online communication with other feminists, and reading online blogs and feminist books. Sharing the company of other women at feminist events such as ‘Reclaim the Night’ marches and conferences was especially valued, particularly if this was a rare opportunity.

Other books

Soul Bound by Anne Hope

El buda de los suburbios by Hanif Kureishi

Devil's Peak by Deon Meyer

Love Inspired May 2015 #1 by Brenda Minton, Felicia Mason, Lorraine Beatty

Fatal Decree by Griffin, H. Terrell

The Reaping of Norah Bentley by Eva Truesdale

Goliath by Alten, Steve

Dead Wake (The Forgotten Coast Florida #5) by Dawn Lee McKenna

Descendant by Eva Truesdale

Big Bad Billionaire (The Woolven Secret Book 1) by DeWylde, Saranna